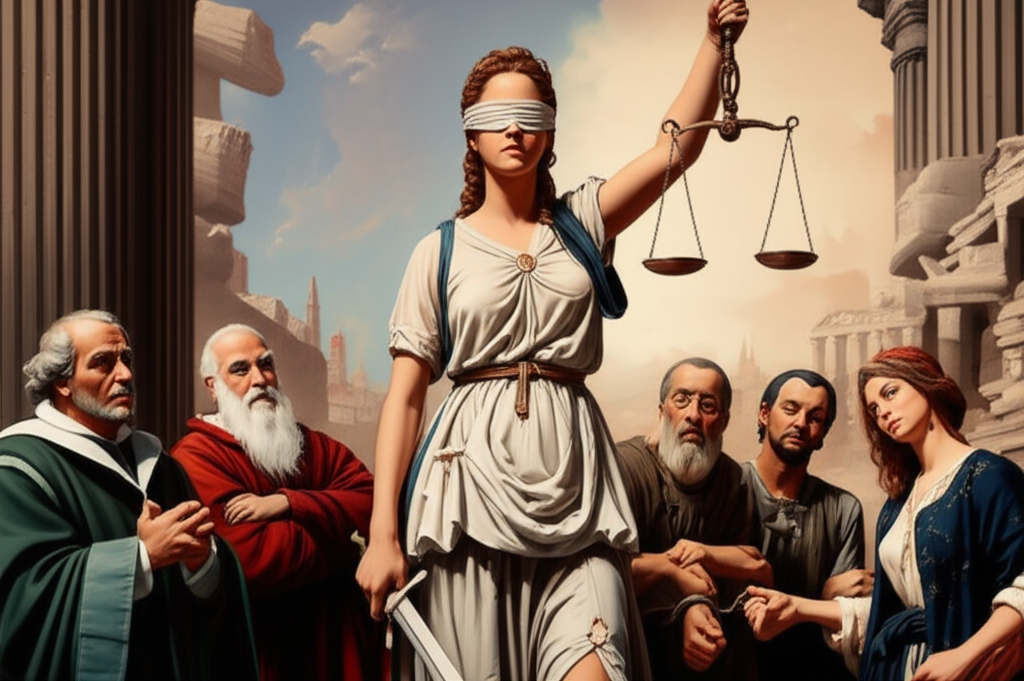

The Idea of a Just Punishment: A Philosophical Inquiry

The concept of a just punishment stands at the very heart of human civilization, a complex intersection where justice, law, morality, and the very definitions of good and evil collide. It’s a question that has preoccupied philosophers, legal scholars, and societies for millennia: What makes a punishment fair, proportionate, and morally defensible? This article delves into the historical philosophical underpinnings of punishment, exploring the various theories that attempt to define its justice, and grappling with the enduring dilemmas that challenge our collective understanding.

Introduction: Grappling with Retribution and Reform

From the earliest codes of conduct to contemporary legal systems, the impulse to punish those who transgress has been a constant. But mere punishment is not enough; it must, we argue, be just. This pursuit of justice in punishment is not merely about retribution or exacting an "eye for an eye." It involves a delicate balance of societal protection, moral accountability, and, increasingly, the potential for rehabilitation. How do we ensure that the imposition of suffering, however deserved, aligns with our deepest ethical principles? This is the enduring question that prompts continuous philosophical reflection.

Echoes from the Great Books: Foundations of Punishment and Justice

Our understanding of justice and punishment is deeply rooted in the philosophical traditions preserved within the Great Books of the Western World. These foundational texts offer diverse perspectives that continue to shape our discourse:

- Plato's Republic: For Plato, justice in the state mirrors justice in the soul – a harmonious balance. Punishment, therefore, isn't primarily about revenge but about the restoration of order, the improvement of the offender, or the education of the citizenry. The goal is to make the individual or society better, moving away from evil and towards good.

- Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics: Aristotle distinguishes between distributive justice (fair allocation of resources) and corrective justice. Punishment falls under corrective justice, aiming to restore the balance disrupted by a wrongful act. It's about rectifying an imbalance, making the scales even again, and ensuring that the law upholds a sense of fairness.

- Augustine and Aquinas: Within the Christian tradition, thinkers like Augustine and Aquinas viewed punishment through the lens of divine law and natural law. Sin, a transgression against God and moral order, often warranted temporal punishment, not just for deterrence or correction, but also as a reflection of the inherent good of God's order and the consequences of evil.

- Immanuel Kant's Metaphysics of Morals: Kant championed a strict retributivist view. For him, punishment is a moral imperative, a duty owed to the offender and to justice itself, independent of any utilitarian outcome. It treats the offender as a rational being who has chosen to violate the moral law, and thus deserves the prescribed consequence. The punishment must be proportionate, not for its deterrent effect, but because it is just.

- John Stuart Mill's Utilitarianism: In contrast, Mill and other utilitarians argue that the justice of punishment lies in its consequences. A punishment is just if it maximizes overall happiness, security, and well-being for society. This perspective emphasizes deterrence (preventing future crime) and rehabilitation (reforming the offender) as the primary justifications, rather than mere retribution for past wrongs.

The Pillars of Punishment: Competing Philosophies

The philosophical theories underpinning punishment can generally be categorized into several key approaches, each offering a different answer to what constitutes just punishment:

- Retributivism:

- Core Idea: Punishment is justified because the offender deserves it for the wrong committed. It is backward-looking, focused on the crime itself.

- Key Principle: Proportionality – "the punishment must fit the crime." This often evokes the principle of lex talionis (an eye for an eye), though modern retributivism focuses more on "just deserts" rather than literal equivalence.

- Goal: To uphold justice by ensuring moral accountability and balancing the scales.

- Deterrence:

- Core Idea: Punishment is justified by its ability to prevent future crimes. It is forward-looking.

- Types:

- Specific Deterrence: Preventing the punished offender from re-offending.

- General Deterrence: Preventing others in society from committing similar crimes by making an example of the offender.

- Goal: To protect society and maintain social order through fear of consequences.

- Rehabilitation:

- Core Idea: Punishment should aim to reform the offender, transforming them into a productive, law-abiding member of society. It is also forward-looking.

- Goal: To address the root causes of criminal behavior and restore the individual to a state of good.

- Restorative Justice:

- Core Idea: Focuses on repairing the harm caused by the crime, involving victims, offenders, and the community in a process of reconciliation and healing.

- Goal: To restore relationships, address needs, and promote accountability in a way that goes beyond mere retribution, seeking a more holistic form of justice.

What Makes Punishment Just? Navigating the Moral Compass

Defining a just punishment is not merely about choosing one theory over another; it often involves an uneasy synthesis of these competing ideals. Several criteria emerge as crucial:

- Proportionality: The severity of the punishment must be commensurate with the gravity of the offense. An excessive punishment is inherently unjust, just as an inadequate one can undermine the rule of law.

- Equity and Impartiality: Justice demands that like cases be treated alike. Punishment must be administered without bias, regardless of an individual's social status, race, or background. The law must apply equally to all.

- Due Process: A just punishment can only be imposed after a fair legal process, ensuring that the accused has the opportunity to defend themselves, that evidence is presented, and that established legal procedures are followed. This safeguards against arbitrary power and the potential for evil within the system itself.

- Minimizing Harm: While punishment inherently involves the imposition of suffering, a just system seeks to minimize unnecessary cruelty and ensure that the punishment does not cause collateral damage disproportionate to its aims.

The Shadow of Good and Evil in the Legal System

The concepts of good and evil are inextricably linked to the idea of just punishment. Criminal acts are often seen as manifestations of evil, or at least as deviations from what society deems good. The law attempts to codify these moral distinctions, defining what acts are permissible and what warrant intervention.

However, the legal system faces profound challenges in translating abstract moral concepts into concrete punishment:

- Defining "Evil": Is evil merely a legal transgression, or does it require a certain intent, a malicious heart? The law often focuses on mens rea (guilty mind) to distinguish between accidental harm and intentional wrongdoing, reflecting a moral judgment about culpability.

- The State as Moral Agent: When the state imposes punishment, it acts as a moral agent, wielding power over individuals. This power must be exercised justly, ensuring it does not become an instrument of oppression or arbitrary evil.

- The Purpose of Punishment: Is punishment meant to purge evil from society, or to guide individuals towards good? The answer often dictates whether we prioritize retribution, deterrence, or rehabilitation.

Contemporary Dilemmas and Enduring Questions

Even with centuries of philosophical thought, the idea of a just punishment remains a source of intense debate.

- Capital Punishment: Is the death penalty ever a just punishment? This question pits retributive claims against concerns about irreversible error, the sanctity of life, and the potential for cruel and unusual punishment.

- Mandatory Minimum Sentences: Do such rigid laws allow for true justice, or do they hinder judges from considering the unique circumstances of each case, potentially leading to disproportionate outcomes?

- The Role of Mercy: Can justice ever be truly served without the possibility of mercy? How does mercy balance the demands of strict law with compassion?

- Restorative vs. Retributive: As societies grapple with high incarceration rates and the limitations of traditional punishment, the appeal of restorative justice grows, challenging the long-held dominance of retributive models.

Conclusion: An Ongoing Quest for Balance

The idea of a just punishment is not a static concept but a dynamic philosophical quest. It demands that we constantly re-evaluate our systems of law, our definitions of good and evil, and our understanding of justice itself. As we navigate the complexities of human behavior and societal needs, the pursuit of truly just punishment remains one of humanity's most profound and necessary intellectual and ethical endeavors. It is a testament to our ongoing commitment to fairness, order, and the enduring hope that even in correction, we can find a path towards a more equitable and humane world.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Michael Sandel Justice What's The Right Thing To Do Punishment"

-

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Great Books of the Western World Plato Justice"