The Enduring Enigma: The Experience of Pleasure and Pain

Unpacking the Primal Sensations of Existence

From the first cry of a newborn to the last sigh of the dying, pleasure and pain are the indelible twin threads woven through the tapestry of human experience. Far from mere biological responses, these fundamental sensations have captivated philosophers for millennia, serving as guiding lights, ethical compasses, and profound mysteries. This article delves into the rich philosophical landscape surrounding the experience of pleasure and pain, exploring how thinkers from the "Great Books of the Western World" have grappled with their nature, their origins in the body and sense, and their profound implications for how we live and understand ourselves. We will journey through ancient insights, examining how these primal forces shape our perceptions, decisions, and ultimately, our pursuit of the good life.

The Primacy of Experience: How We Know Pleasure and Pain

At its core, the experience of pleasure and pain is intensely personal and immediate. It is the raw data of our existence, signaling well-being or threat, comfort or discomfort. Before we conceptualize, before we rationalize, we feel. This immediate, subjective quality makes them challenging subjects for objective analysis, yet indispensable for understanding human motivation and morality.

The philosophers of antiquity understood this immediacy. They recognized that our very interaction with the world is mediated through our senses, and it is through these senses that the body registers the impact of external stimuli and internal states as either pleasurable or painful. This isn't just a physical phenomenon; it's a gateway to understanding consciousness itself.

Ancient Echoes: Philosophical Perspectives on Pleasure and Pain

The "Great Books of the Western World" offer a profound repository of thought on pleasure and pain, revealing diverse and often conflicting interpretations.

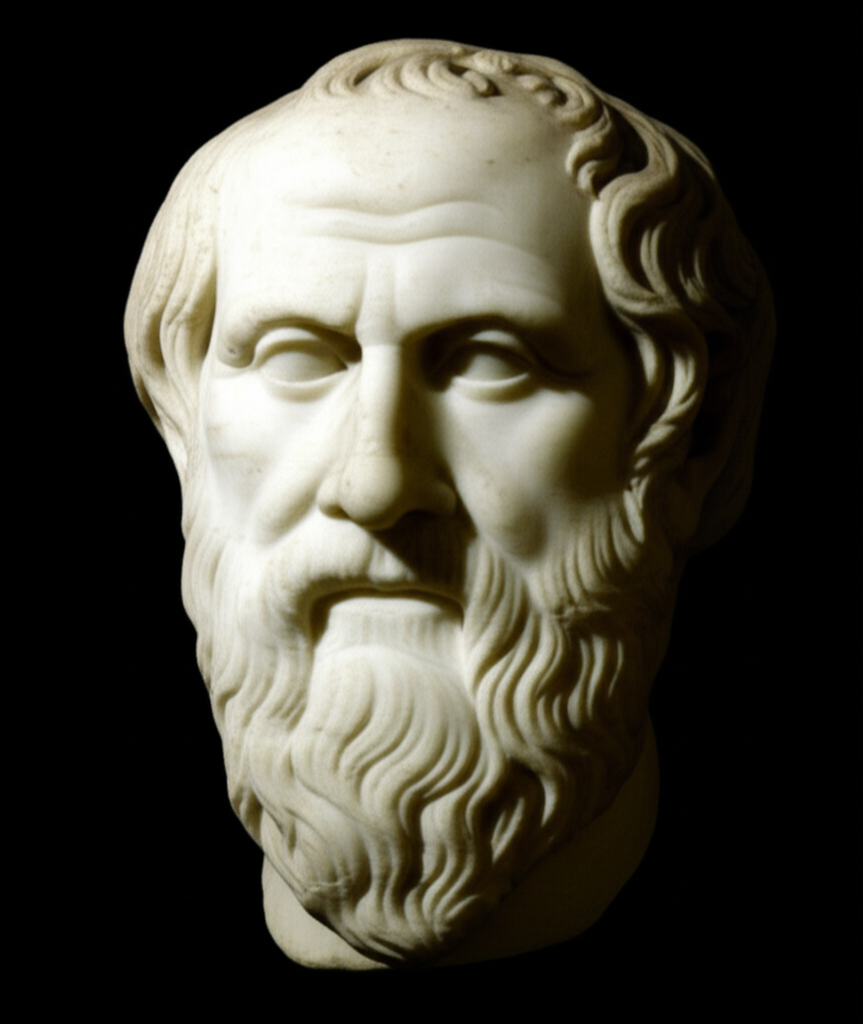

Plato: The Soul's Struggle and the Illusion of Pleasure

For Plato, as explored in dialogues like Philebus, pleasure and pain are often seen in relation to the soul's harmony or disharmony. Pleasure, particularly sensual pleasure, is frequently depicted as a temporary cessation of pain or a filling of a lack. Eating, for instance, is pleasurable because it relieves the pain of hunger. True, pure pleasures, for Plato, are those of the mind and the contemplation of eternal Forms, untainted by bodily needs. Sensual pleasures are fleeting and can mislead the soul, drawing it away from the pursuit of wisdom and virtue. The body is often a source of distraction and unreliability in this pursuit.

Aristotle: Pleasure as a Concomitant of Activity

Aristotle, in works like the Nicomachean Ethics, offers a more nuanced view. He argues that pleasure is not a movement or a process, but rather a perfect completion of an activity. When an activity is unimpeded and performed well, pleasure arises as a supervening end, like the bloom on youth. It is not the goal of the activity, but an indicator that the activity is being performed excellently. Pain, conversely, signals an impediment or defect in an activity. For Aristotle, the highest pleasure is found in the highest activity – contemplation – which engages the rational faculty of the soul, distinct from the more visceral sensations of the body.

Epicurus: The Pursuit of Tranquility

Often misunderstood as advocating for hedonistic indulgence, Epicurus, as conveyed through his Letter to Menoeceus, defined pleasure primarily as the absence of pain in the body (aponia) and disturbance in the soul (ataraxia). His philosophy was not about seeking intense, fleeting pleasures, but about achieving a state of tranquil contentment through moderation, self-sufficiency, and friendship. The highest good, for Epicurus, was this state of freedom from suffering, achieved by understanding and managing desires, rather than endlessly pursuing them.

The Stoics: Indifference and Virtue

The Stoics, represented by figures like Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius, took a radically different approach. They argued that pleasure and pain are "indifferents" – external things that do not contribute to true happiness or virtue. The wise person cultivates apatheia, not apathy in the modern sense, but freedom from emotional disturbance, including the sway of pleasure and pain. Virtue lies in living in accordance with reason and nature, accepting what is beyond our control, and not allowing the fleeting sensations of the body to dictate our inner state.

The Body as the Vessel of Sensation

Regardless of their ethical conclusions, all these philosophers acknowledged the fundamental role of the body in the experience of pleasure and pain. Our nervous system, our physiological responses, our very physical existence are the substrate upon which these sensations are built. The warmth of the sun, the sting of a nettle, the taste of a sweet fruit, the ache of a broken bone – all are registered first and foremost by the body through its intricate network of senses.

This undeniable physicality grounds the philosophical debate. How much influence should these bodily sensations have over our rational mind? Are they reliable guides, or potential deceivers? The answers to these questions have shaped ethical systems and personal philosophies for millennia.

The Ethical Imperative: Navigating Pleasure and Pain

The philosophical inquiry into pleasure and pain is never purely descriptive; it is deeply prescriptive. How we understand these experiences profoundly impacts our ethical frameworks and our pursuit of a meaningful life.

| Philosophical School | View on Pleasure | View on Pain | Ethical Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platonism | Often a cessation of pain; highest pleasures are intellectual. | Sign of disharmony or lack. | Pursue intellectual virtues; beware bodily desires. |

| Aristotelianism | A sign of excellent, unimpeded activity. | A sign of impeded or flawed activity. | Engage in virtuous activity; pleasure will follow. |

| Epicureanism | Absence of pain in the body and disturbance in the soul. | To be avoided; a state of suffering. | Seek tranquility (ataraxia) and freedom from suffering. |

| Stoicism | An "indifferent"; not inherently good or bad. | An "indifferent"; not inherently good or bad. | Cultivate virtue and reason; be indifferent to external sensations. |

Conclusion: The Enduring Philosophical Challenge

The experience of pleasure and pain remains one of philosophy's most enduring and complex subjects. From the ancient Greeks who sought to understand their nature and role in the good life, to modern neuroscientists exploring their biological underpinnings, these primal sensations continue to challenge our understanding of consciousness, morality, and human flourishing. They are not merely simple feelings but profound indicators, shaping our perception of reality, guiding our actions, and ultimately defining much of what it means to be human. To grapple with pleasure and pain is to grapple with the very fabric of our experience, our sense of self, and our connection to the world through our body.

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Aristotle pleasure pain ethics", "Epicurean philosophy pleasure pain""