The Dual Edges of Existence: A Philosophical Inquiry into Pleasure and Pain

Pleasure and pain are fundamental to the human experience, serving as primal motivators and indicators of our interaction with the world. This article explores how philosophers, from ancient Greece to the Enlightenment, have grappled with these core sensations, examining their nature, their connection to the body and sense, and their profound impact on our understanding of consciousness and well-being. Drawing insights from the Great Books of the Western World, we delve into the subjective and objective dimensions of these inescapable forces that shape our very being.

The Intimate Dance of Being: An Introduction

From the first cry of an infant to the reflective wisdom of old age, the oscillating currents of pleasure and pain define much of what it means to be alive. They are the immediate, often overwhelming, feedback mechanisms that guide our actions, shape our perceptions, and color our memories. But what, precisely, are these sensations? Are they merely biological signals, or do they possess a deeper philosophical significance? This inquiry aims to navigate the rich tapestry of thought surrounding the experience of these fundamental states, examining how they are processed by the body and interpreted by the mind, often through the intricate workings of our sense organs.

The Primal Duality: Defining Pleasure and Pain

At their most basic, pleasure and pain represent the poles of our affective landscape. Pleasure is often associated with well-being, satisfaction, and the continuation of life-sustaining activities. Pain, conversely, signals threat, damage, or dis-ease, acting as an urgent call to attention and withdrawal. Yet, their definitions are far from simple. Is pleasure merely the absence of pain, or is it a positive state in itself? Is pain purely physical, or can it be entirely psychological? The Great Books of the Western World reveal a long-standing debate on this very distinction, challenging us to look beyond immediate sensation.

The Embodied Experience: Sense and Body

Our primary interface with pleasure and pain is undoubtedly through the body and its intricate network of sense organs. From the warmth of the sun on our skin to the sharp sting of a cut, these sensations are profoundly embodied. Aristotle, in his Nicomachean Ethics, recognized that pleasure is often a concomitant of unimpeded activity, particularly the exercise of our senses and faculties. Pain, then, is an impediment to such activity. The very structure of our nervous system is designed to register, transmit, and interpret these signals, turning raw sensory input into a conscious experience of comfort or discomfort.

Philosophical Lenses: Perspectives from the Great Books

The profound impact of pleasure and pain on human life has made them central to philosophical inquiry across millennia.

-

Plato and the Forms: For Plato, as discussed in dialogues like the Philebus, pleasure and pain are often linked to the body's condition and its striving towards or away from a state of balance. True pleasure, for Plato, was often associated with the pursuit of knowledge and the contemplation of the Forms, a higher, purer experience than mere bodily gratification.

-

Aristotle's Eudaimonia: Aristotle, more grounded in the empirical, saw pleasure as a natural accompaniment to virtuous activity, not the end goal itself. It perfects the activity, making it more desirable. Pain, conversely, is a departure from our natural state, an indicator of something amiss with the body or soul. His concept of eudaimonia (flourishing) implies a life where the proper balance of pleasure and pain allows for the full actualization of human potential.

-

Epicurus and Ataraxia: Epicurus, famously misinterpreted, advocated for a life free from disturbance. For him, the highest good was ataraxia (tranquility) and aponia (absence of pain in the body). He argued that pleasure is simply the absence of pain, and true contentment lies in minimizing suffering and cultivating simple, natural desires. This perspective profoundly shaped later philosophical discussions on hedonism and well-being, emphasizing the role of rational choice in managing our experience of these sensations.

-

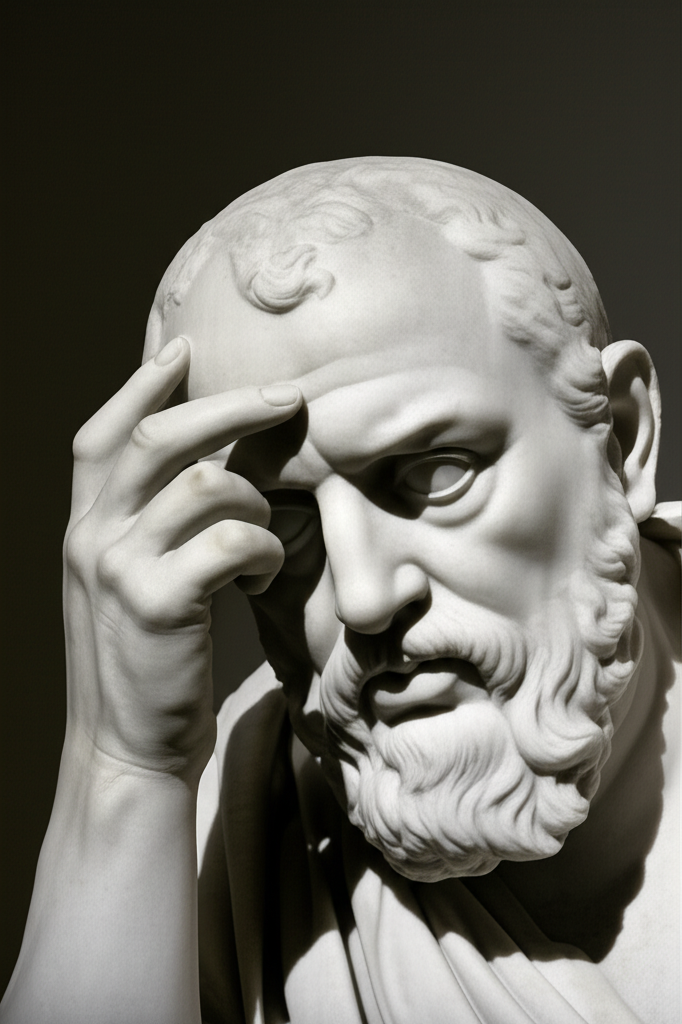

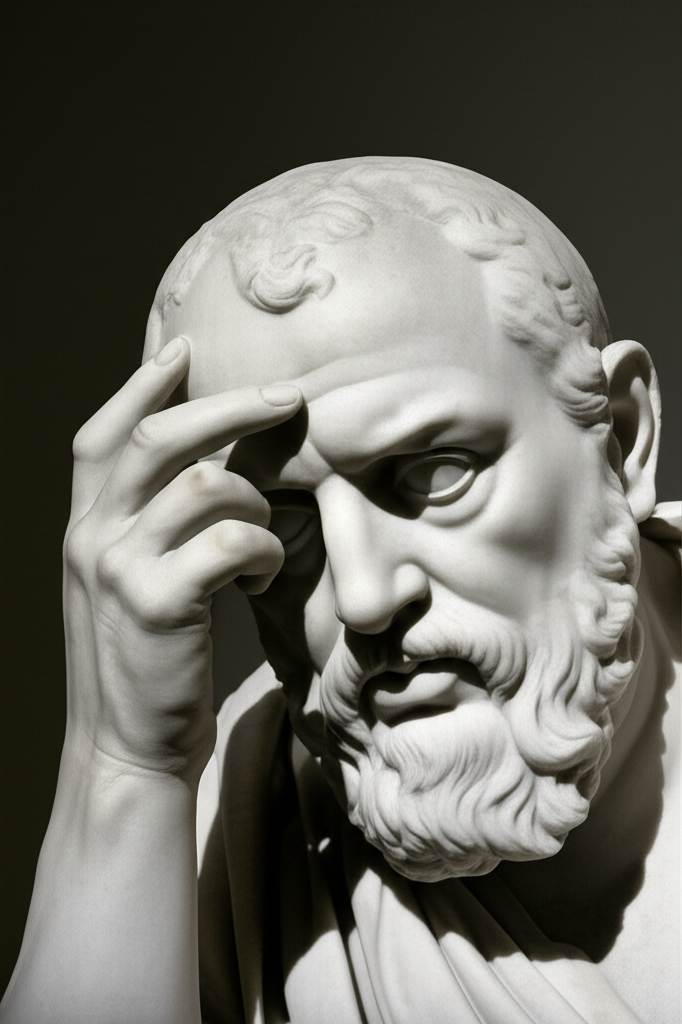

The Stoic Indifference: In stark contrast, the Stoics, such as Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius, taught that true wisdom lies in cultivating indifference to external circumstances, including pleasure and pain. These sensations are indifferents – neither good nor bad in themselves – and our suffering arises not from the sensations themselves, but from our judgments about them. The goal was to achieve apatheia, not apathy in the modern sense, but freedom from disruptive passions, allowing reason to guide one's experience.

-

Descartes and the Mind-Body Problem: With René Descartes, the discussion shifts towards the mechanics of experience. His dualism, proposing a distinct mind and body, raised profound questions about how physical pain in the body could translate into a mental experience of suffering. How does the pineal gland, his proposed seat of interaction, bridge the gap between mechanical sense data and conscious anguish or delight? This inquiry laid the groundwork for modern neuroscience and philosophy of mind.

-

Locke, Hume, and Empiricism: John Locke, in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding, described pleasure and pain as simple ideas, the foundation of all our motivations. David Hume further explored their role as 'impressions' – vivid and immediate experiences that form the basis of our passions and moral sentiments. For these empiricists, our sense data are paramount, and pleasure and pain are the most direct and influential of these sensory inputs, shaping our very understanding of good and evil.

The Subjectivity of the Experience

Despite extensive philosophical debate, one truth remains constant: the experience of pleasure and pain is profoundly subjective. What one person finds delightful, another might find irritating; what constitutes unbearable pain for one, another might endure with stoicism. This individual variance underscores the complex interplay between physical sensation, psychological interpretation, cultural conditioning, and personal history. Our body provides the raw data, but our mind, informed by a lifetime of experience, crafts the final sensation.

Conclusion: Navigating the Human Condition

The philosophical journey through pleasure and pain reveals them not as mere biological reflexes, but as profound elements of the human condition, central to ethics, metaphysics, and epistemology. From the ancient Greeks seeking eudaimonia to Enlightenment thinkers dissecting the mechanics of sense and consciousness, the Great Books of the Western World offer a continuous dialogue on these dual edges of existence. Understanding this intricate experience — how our body registers, and our mind interprets these fundamental sensations — is to understand a significant part of what it means to live, to suffer, and to flourish.

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Philosophy of Pleasure and Pain Ancient Greece""

📹 Related Video: KANT ON: What is Enlightenment?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Descartes Mind Body Problem Pain Experience""