The Primal Symphony: Deconstructing the Experience of Pleasure and Pain

The experience of pleasure and pain forms the bedrock of our existence, guiding our actions, shaping our perceptions, and profoundly influencing our philosophical inquiries. Far from mere physical sensations, these dual forces represent a complex interplay between our body, our sense organs, and our interpretative minds. This article delves into the rich history of how Western thought, particularly as captured in the Great Books of the Western World, has grappled with these fundamental phenomena, exploring their nature, their origins, and their enduring significance to the human condition.

The Inescapable Duality: Pleasure and Pain as Existential Guides

From the first breath to the last, pleasure and pain are the most immediate and universal teachers we encounter. They are the primal signals that tell us what to approach and what to avoid, what sustains life and what threatens it. This inherent duality is not merely biological; it underpins much of our ethical, aesthetic, and metaphysical understanding. Philosophers across millennia have recognized that to understand the human being, one must first confront the nature of these powerful, often contradictory, sensations. How we define, interpret, and respond to pleasure and pain speaks volumes about our values, our pursuit of happiness, and our confrontation with suffering.

Through the Lens of the Ancients: A Philosophical Tapestry

The philosophical contemplation of pleasure and pain is as old as philosophy itself. The Great Books of the Western World offer a profound lineage of thought, illustrating how different schools sought to categorize, contextualize, and even transcend these powerful forces.

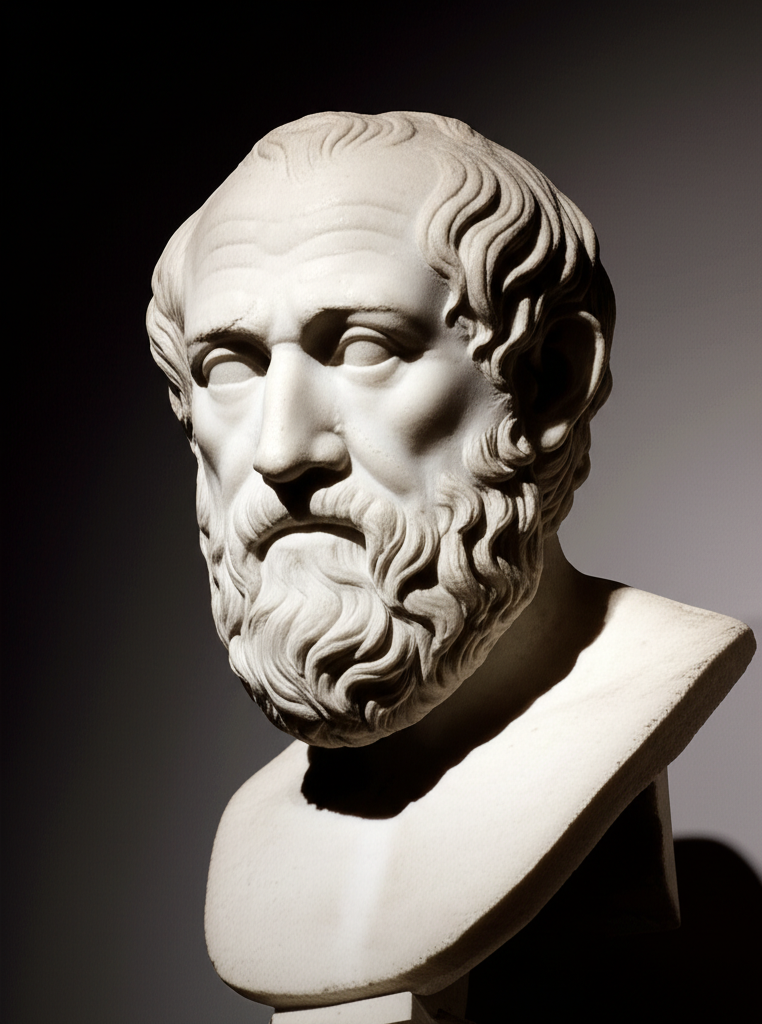

Early Greek Perspectives

- Plato, in dialogues like the Philebus, often viewed pleasure with suspicion, distinguishing between "pure" pleasures (like those of knowledge or beautiful forms) and "mixed" pleasures (those that arise from the cessation of pain, like scratching an itch). For Plato, true pleasure was linked to the good and the rational, while bodily pleasures were often illusory or fleeting. Pain, conversely, was a disturbance, a state of disharmony.

- Aristotle, in the Nicomachean Ethics, offered a more nuanced view. He saw pleasure not as a process of becoming, but as the perfection of an activity – the full and unimpeded exercise of a natural faculty. A good activity, well performed, brings pleasure. Pain, then, impedes activity and is generally to be avoided, though some pains can be necessary for growth or virtue.

Hellenistic Schools: Navigating the Tides of Sensation

With the Hellenistic philosophers, the focus shifted towards achieving tranquility and a good life in the face of an often chaotic world.

- Epicurus famously posited that the highest good was pleasure, but he defined it not as sensual indulgence, but as ataraxia (freedom from mental disturbance) and aponia (absence of bodily pain). For Epicurus, the ultimate experience of pleasure was a state of serene equilibrium, achieved by minimizing pain and fear.

- The Stoics, on the other hand, advocated for apatheia, an indifference to external pleasure and pain. They believed that virtue was the sole good, and that our reactions to external events, rather than the events themselves, determined our suffering. Pain was an adiaphoron – an indifferent thing – which the wise person could endure with equanimity through rational judgment.

Here's a brief comparison of some key ancient perspectives:

| Philosopher/School | Primary View on Pleasure | Primary View on Pain | Role of the Body/Sense |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plato | True pleasure is intellectual/pure; bodily pleasures are often deceptive/mixed. | A state of lack, disturbance, or disharmony. | Bodily senses can mislead; the body is a prison. |

| Aristotle | Perfection of an activity; accompanies well-performed functions. | An impediment to activity; generally undesirable. | The body and its sense organs are integral to experience, but reason guides. |

| Epicurus | Ataraxia (mental tranquility) and Aponia (absence of bodily pain). | To be avoided for peace; disturbance of mind/body. | The body's comfort/discomfort is central to well-being. |

| Stoics | Indifferent (adiaphoron); not inherently good or bad. | Indifferent (adiaphoron); to be rationally endured. | Sense perceptions are raw data; reason determines response, not the body's feelings. |

The Embodied Experience: Sense, Body, and the Immediate Now

Regardless of philosophical interpretation, the initial encounter with pleasure and pain is undeniably physical. Our body is the primary conduit through which these sensations register. Nerves, receptors, and neurological pathways translate external stimuli or internal states into raw data. A sharp prick, a warm embrace, a growling stomach – these are first and foremost signals received by our sense organs and transmitted to the brain.

This immediate, visceral experience is crucial. It’s the raw material upon which our minds then operate. The warmth of the sun on our skin is a sense perception that our mind labels as pleasure. The ache of a strained muscle is a body sensation immediately categorized as pain. This foundational layer of physical experience is what connects us to all sentient beings and forms the universal language of well-being and distress.

Beyond Mere Sensation: The Cognitive and Cultural Dimensions

While the body and its sense organs provide the initial input, the experience of pleasure and pain is far from a simple reflex. Our minds actively interpret, contextualize, and assign meaning to these sensations.

- Memory and Anticipation: Past experiences of pleasure or pain shape our current reactions. A smell that once accompanied a joyous event can evoke pleasure, while the sight of an object associated with previous pain can trigger anxiety. Anticipation of future pleasure or pain also profoundly influences our present state.

- Cultural and Social Norms: What is considered pleasurable or painful can vary across cultures. The tolerance for pain, the types of activities deemed enjoyable, and the ways we express distress are all influenced by our societal upbringing.

- Personal Interpretation: The same physical sensation can be experienced differently by individuals. The pain of intense exercise might be a source of satisfaction for an athlete, signaling progress, while for another, it might be purely aversive. This highlights that pleasure and pain are not just objective states, but subjective interpretations.

The Paradox of Pain and the Pursuit of Meaning

Interestingly, humans sometimes seek out experiences that involve pain – not for the pain itself, but for what it signifies or leads to. The pain of childbirth, the rigor of academic study, the emotional anguish of personal growth – these are often endured, or even embraced, because they are perceived as necessary steps towards a greater good or a more profound experience of life. This paradox suggests that our relationship with pleasure and pain is deeply intertwined with our search for meaning and purpose. It challenges simplistic hedonistic views and underscores the complexity of human motivation.

Conclusion: An Ongoing Inquiry

The experience of pleasure and pain remains one of philosophy's most enduring and fundamental inquiries. From the ancient Greeks who sought to understand their role in the good life, to modern neuroscience mapping their neurological pathways, these sensations compel us to ask profound questions about our nature, our values, and the very fabric of existence. They are the primal forces that delineate the boundaries of our being, pushing us towards growth, warning us of danger, and continually reminding us of the intricate dance between our body, our sense of the world, and the meaning we create from it all. To truly comprehend the human condition is to grapple with this inescapable, essential duality.

📹 Related Video: STOICISM: The Philosophy of Happiness

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Ancient Greek Philosophy Pleasure Pain", "Epicureanism and Stoicism on Pleasure""