The Ethical Compass: Navigating Temperance and Desire

Summary

The ethical relationship between temperance and desire forms a cornerstone of Western philosophy, profoundly explored within the Great Books of the Western World. This article delves into how ancient thinkers, from Plato to Aristotle, understood desire not merely as an impulse, but as a force requiring rational governance. Temperance emerges as a cardinal virtue, a balanced state of self-mastery that distinguishes a well-ordered soul from one prone to vice. We will explore how these concepts illuminate the path to an ethical life, offering timeless insights into human flourishing.

The Eternal Dance of Desire and Restraint

Human existence is a constant interplay between our innate urges and our capacity for reasoned choice. From the most basic physiological needs to the loftiest aspirations, desire fuels our actions. Yet, unchecked, these desires can lead to discord, harm, and the erosion of individual and societal well-being. This fundamental tension is precisely what the concept of temperance seeks to address, positioning it as an indispensable element of ethics.

The philosophers of antiquity, whose works comprise the bedrock of the Great Books, didn't merely condemn desire; rather, they sought to understand its nature and its proper place within a virtuous life. Their insights provide a robust framework for understanding how to live well, not by denying our desires, but by mastering them.

Defining the Core Concepts

To truly grasp the ethical implications, we must first clearly define our terms as understood by the great minds of the past.

-

Desire (Epithymia/Eros):

- In philosophy, desire encompasses a broad spectrum of human appetites, urges, and longings. Plato, in the Republic, famously categorizes the soul into three parts: the rational, the spirited, and the appetitive. The appetitive part is the seat of our basic desires for food, drink, sex, and material possessions. Aristotle, in the Nicomachean Ethics, further refines this, distinguishing between natural and unnatural desires, and necessary versus unnecessary ones.

- Not all desires are inherently bad. Natural and necessary desires (like hunger) are essential for survival. The ethical challenge arises when desires become excessive, misplaced, or directed towards harmful ends.

-

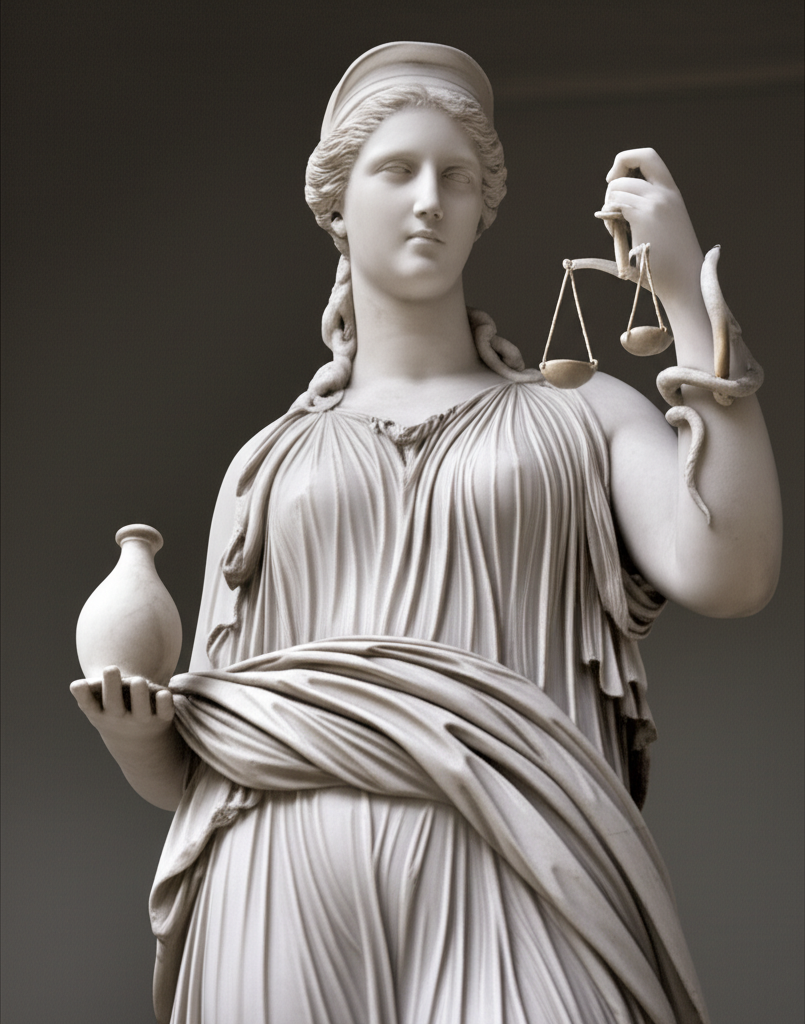

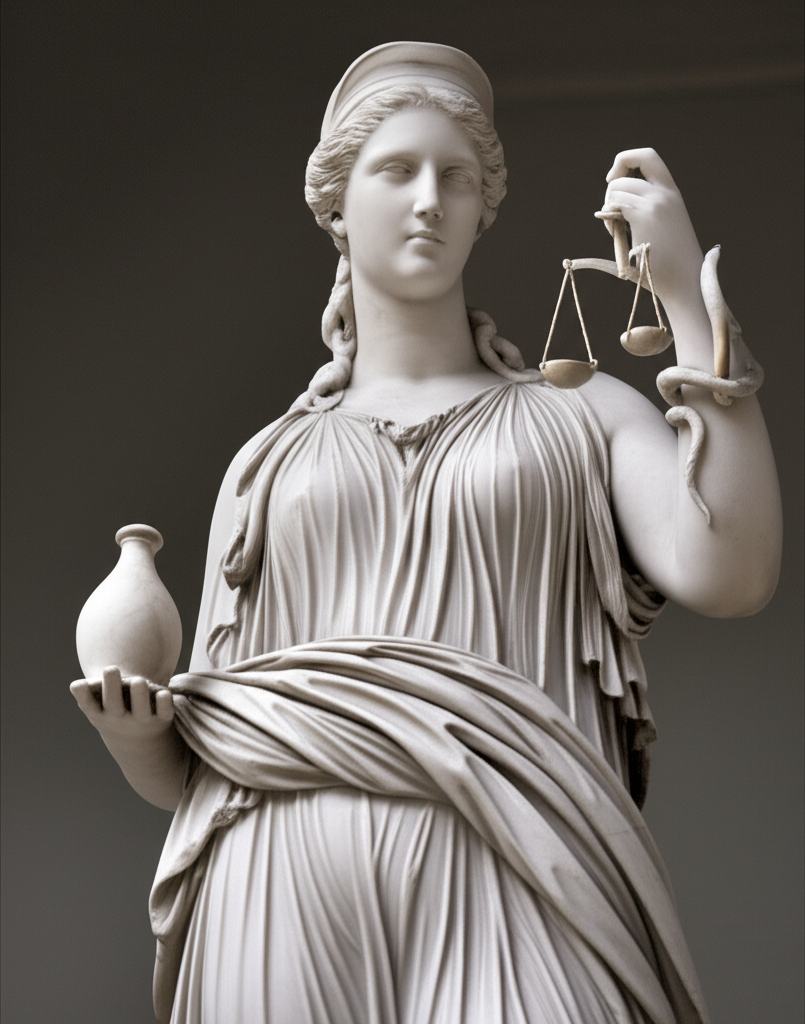

Temperance (Sophrosyne):

- Often translated as moderation, self-control, or soundness of mind, temperance is far more than mere abstinence. It is the virtue of rationally governing one's desires and pleasures, ensuring they remain within appropriate bounds. For Plato, temperance is a state of harmony where the rational part of the soul guides the appetitive and spirited parts. For Aristotle, it is a mean between the vice of insensibility (deficiency) and self-indulgence (excess) concerning bodily pleasures.

- Temperance, therefore, is an active, conscious effort to align our inner wants with our reasoned judgment and moral principles.

-

Ethics:

- This refers to the systematic study of moral principles and values, and the rules of conduct that govern a group or individual. In the context of temperance and desire, ethics provides the framework for evaluating which desires are good, which are harmful, and how we ought to cultivate the virtue of temperance to live a morally upright and fulfilling life.

Temperance as a Cardinal Virtue

Throughout the Great Books, temperance stands as a cornerstone of the good life, often listed among the cardinal virtues alongside wisdom, courage, and justice.

- Plato's Harmony of the Soul: In the Republic, Plato argues that a just individual, like a just city, is one where each part performs its proper function in harmony. Temperance is precisely this harmonious agreement among the parts of the soul—the rational part exercising authority over the appetitive desires. Without temperance, the soul is chaotic, driven by base impulses, incapable of true wisdom or courage.

- Aristotle's Golden Mean: Aristotle dedicates significant attention to temperance in the Nicomachean Ethics. He defines virtue as a mean between two extremes, two vices. Temperance, in this view, is the desirable middle ground concerning pleasures and pains, particularly those of touch and taste. The temperate person enjoys pleasures appropriately and in moderation, neither indulging excessively nor being insensitive to them. This rational enjoyment, rather than suppression, is key to Aristotelian temperance.

- Stoic Mastery of Passions: While perhaps more austere, Stoic philosophers like Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius also championed a form of temperance. For them, true freedom lay in mastering one's passions (which include desires, fears, and pleasures) and aligning oneself with reason and nature. This mastery, while not necessarily a "mean," shares the fundamental goal of preventing desires from dictating one's actions and disturbing one's inner tranquility.

The Perils of Unchecked Desire: The Vice of Intemperance

The antithesis of temperance is intemperance, a vice characterized by a lack of self-control and an excessive indulgence in desires. The Great Books are replete with cautionary tales and philosophical analyses of its destructive power.

- Slavery to Appetite: Philosophers consistently warned that an individual enslaved by their desires is not truly free. The intemperate person is driven by external stimuli and internal cravings, rather than by rational choice. This leads to a loss of autonomy and often, to regret and suffering.

- Moral Decay: Unchecked desires for pleasure, wealth, or power can corrupt the soul, leading to other vices such as gluttony, lust, greed, and tyranny. Plato vividly illustrates how the "tyrannical man" is ultimately miserable, driven by insatiable desires that can never truly be satisfied.

- Societal Disruption: When individuals within a society lack temperance, the social fabric itself can fray. Excessive self-indulgence, disregard for others, and the pursuit of selfish desires at all costs can lead to injustice, conflict, and the breakdown of communal harmony.

Navigating the Spectrum of Desire

It's crucial to understand that the ethical project is not about eradicating desire, but about discerning and managing it. Ancient philosophers provided frameworks for distinguishing between different types of desires and their ethical implications.

| Type of Desire | Description | Ethical Implication | Philosophical Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural & Necessary | Essential for survival and well-being (e.g., food, shelter, sleep). | Good and ethically permissible when satisfied appropriately. | Plato (Appetitive part), Aristotle (Basic needs) |

| Natural & Unnecessary | Pleasures that enhance life but aren't essential (e.g., gourmet food, luxury). | Neutral, but require temperance to prevent excess and dependency. | Aristotle (Pleasures beyond basic sustenance) |

| Unnatural & Unnecessary | Desires for things not intrinsically good or necessary (e.g., excessive wealth, vain glory, power for its own sake). | Often leads to vice, moral corruption, and unhappiness. Requires strict rational control. | Plato (Tyrannical desires), Stoics (External indifferents) |

The ethical challenge lies in cultivating the wisdom to differentiate between these desires and the virtue of temperance to respond to them appropriately. This discernment prevents us from becoming slaves to fleeting pleasures while still allowing us to enjoy the good things life offers in moderation.

Modern Relevance: Temperance in a Consumerist World

The insights from the Great Books on temperance and desire remain remarkably pertinent today. In a world characterized by instant gratification, relentless consumerism, and the constant stimulation of our appetites, the ancient call for self-mastery is more vital than ever. The struggle against vice and for virtue is not confined to ancient city-states; it plays out daily in our personal choices, our digital interactions, and our societal priorities. Embracing temperance means consciously choosing thoughtful consumption over mindless acquisition, mindful engagement over passive indulgence, and genuine well-being over fleeting pleasure.

Conclusion: The Path to Eudaimonia

The ethical examination of temperance and desire reveals a profound truth: true freedom and flourishing (eudaimonia) are not found in the unbridled pursuit of every whim, but in the rational governance of our inner lives. By cultivating the virtue of temperance, we align our actions with our higher reason, fostering inner harmony and contributing to a more just and balanced world. The wisdom contained within the Great Books of the Western World continues to guide us, urging us to become masters of ourselves rather than slaves to our appetites, thereby charting a course towards a truly ethical and fulfilling existence.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato Temperance Republic" and "Aristotle Nicomachean Ethics Temperance""