The Ethics of Desire: Navigating the Labyrinth of Human Aspiration

The human experience is inextricably bound to desire. From the primal urge for sustenance to the loftiest aspirations for truth and beauty, desire propels us, shapes our choices, and defines our very being. But is desire inherently good, evil, or merely a neutral force awaiting the direction of our will? This question lies at the heart of "The Ethics of Desire," a profound philosophical inquiry that has occupied thinkers across millennia, prompting us to scrutinize the moral compass by which we navigate our deepest yearnings. Through the lens of the Great Books of the Western World, we embark on a journey to understand how our desires interact with our will, informing our concepts of good and evil, and ultimately, our ethical conduct.

Ancient Echoes: Desire as Appetite and Aspiration

The earliest philosophical inquiries into desire often distinguished between base appetites and noble aspirations, placing the faculty of reason as the arbiter.

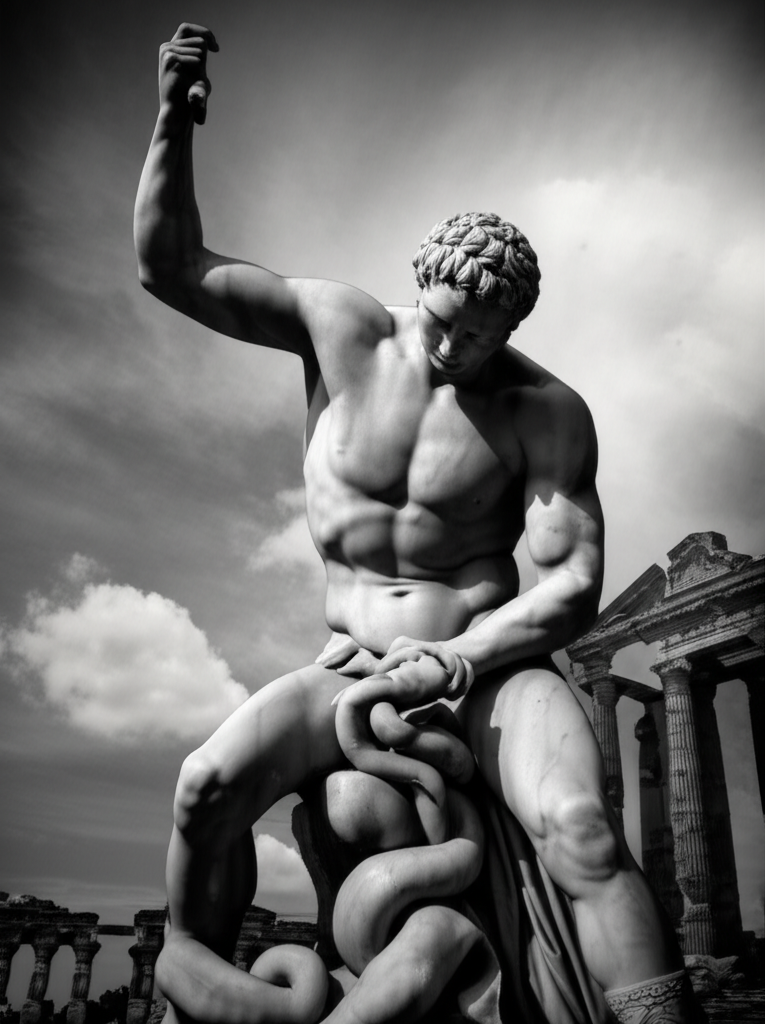

Plato's Chariot: Reason, Spirit, and Appetite

Plato, in his Phaedrus, famously depicts the soul as a charioteer (reason) guiding two winged horses: one noble and striving upwards (spirit/honor), the other unruly and dragging downwards (appetite/desire). For Plato, ethical living demanded that reason assert control over the appetites, directing the soul towards the Forms of the Good. Unchecked desires, particularly those for bodily pleasures, could lead to moral degradation and a life far from eudaimonia, or flourishing. The will here is implicitly tied to the charioteer's ability to steer.

Aristotle's Golden Mean: Desire in Pursuit of Virtue

Aristotle, in his Nicomachean Ethics, offers a more nuanced view. He recognized that desires are natural and necessary components of human life. The ethical challenge isn't to eradicate desire, but to moderate it through the cultivation of virtues. For Aristotle, virtue lies in the "golden mean" between excess and deficiency. For instance, courage is the mean between recklessness and cowardice, both driven by desires (for glory or safety, respectively). The will plays a crucial role in habituating oneself to virtuous action, thereby shaping one's desires to align with what is truly good. Desires, when rightly ordered by reason and will, contribute to a virtuous life and the ultimate good of human flourishing.

The Christian Perspective: Divine Will and Human Longing

With the advent of Christian thought, the ethics of desire took on a new dimension, heavily influenced by the concept of God's will and the nature of sin.

Augustine's Confessions: Love, Sin, and Grace

Saint Augustine, in his Confessions, grapples intensely with the nature of desire. He distinguishes between caritas (charitable love directed towards God) and cupiditas (selfish desire directed towards worldly things). For Augustine, human will is fallen; it is weak and prone to evil due to original sin, leading us to desire things contrary to God's will. True ethical living, therefore, involves redirecting one's desires towards God, a process made possible only through divine grace. The struggle against sinful desires is central to his ethics, where the will is seen as constantly battling its own inclinations.

Aquinas and the Natural Law: Ordered Desires

Thomas Aquinas, drawing upon Aristotle and Christian doctrine, posited that human beings have natural inclinations (desires) towards the good—to preserve life, to procreate, to seek truth, and to live in society. These inclinations are part of the Natural Law, reflecting God's will. Ethical will involves aligning one's particular desires with these natural inclinations, guided by reason and divine law. Desires that lead us away from these fundamental goods are deemed evil. The will acts as the rational appetite, choosing among various goods, and its ethical quality depends on its conformity to right reason and divine purpose.

Modernity's Shifting Sands: Duty, Power, and Authenticity

The Enlightenment and subsequent philosophical movements brought radical re-evaluations of desire, will, and their ethical implications.

Kant's Categorical Imperative: Duty Over Inclination

Immanuel Kant offered a stark contrast to earlier views. For Kant, true moral action is not driven by desire or inclination, but by duty, derived from pure practical reason. The will is moral only when it acts out of respect for the moral law, embodied in the Categorical Imperative ("Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law"). Desires, being contingent and subjective, cannot be the basis for universal moral principles. An action performed from desire, even if it leads to a good outcome, lacks moral worth if it is not done purely from duty. Here, will is supreme, demanding that we transcend our desires to embrace universal moral law, defining good as acting from duty, and evil as acting against it.

Nietzsche's Will to Power: Revaluing Values

Friedrich Nietzsche radically reoriented the discussion, positing the "Will to Power" as the fundamental driving force of all existence. For Nietzsche, traditional morality, particularly Christian ethics, had suppressed and condemned natural human desires, labeling them as evil to control the strong. He called for a "revaluation of all values," where individuals embrace their creative will and powerful desires to overcome existing norms and create new ones. Ethical living, in this view, is not about curbing desire but about asserting and transforming it, pushing beyond conventional notions of good and evil to achieve self-overcoming and greatness.

The Interplay of Desire, Will, and Ethics: A Dynamic Relationship

The historical survey reveals a complex and dynamic relationship between desire, will, and ethics.

- Desire Informs Will: Our innate desires often present the initial impetus for action. The desire for happiness, for knowledge, for connection—these are the raw materials the will must contend with.

- Will Directs Desire: The will is not merely a passive recipient of desires but an active faculty that can choose to pursue, suppress, or reshape them. It is the seat of moral agency.

- Ethics as the Framework: Ethical systems provide the principles by which we judge the moral quality of our desires and the actions of our will. They help us distinguish between desires that lead to good and those that lead to evil.

Core Ethical Considerations for Desire

| Philosophical Stance | Role of Desire | Role of Will | Ethical Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plato/Aristotle | Appetites (lower) vs. Aspirations (higher) | Reason's control, habituation to virtue | Eudaimonia (flourishing), virtuous character |

| Augustine/Aquinas | Inclinations (natural), cupiditas (sinful) | Aligns with divine will, seeks grace | Salvation, ordered love, conformity to Natural Law |

| Kant | Inclination (non-moral) | Acts from duty, respects moral law | Moral worth, universalizability |

| Nietzsche | Expression of Will to Power | Self-overcoming, creation of new values | Self-mastery, strength, transcending old morality |

Navigating the Labyrinth: Practical Ethics of Desire

So, how do we, as individuals, navigate the ethical labyrinth of our desires? The Great Books offer enduring wisdom:

- Self-Knowledge: Understanding the nature and origin of our desires is the first step. Are they genuine needs, fleeting whims, or ingrained habits?

- Rational Deliberation: Employing reason to evaluate desires, considering their potential consequences for ourselves and others. Does this desire align with a greater good?

- Cultivation of Virtue: Developing habits of moderation, courage, justice, and temperance helps to order our desires and strengthen our will.

- Moral Framework: Adopting or developing a coherent ethical framework (be it duty-based, virtue-based, or consequentialist) provides principles for guiding our will in relation to our desires.

The ethics of desire is not about eradicating our passions, which is often impossible and perhaps undesirable, but about understanding, directing, and transforming them. It is the lifelong project of aligning our internal longings with our highest ethical aspirations, making our will an instrument of good rather than a slave to evil.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Chariot Allegory Explained" and "Kant on Duty vs. Inclination""