The Primordial Fluid: Water as a Foundational Element in Ancient Cosmology

From the earliest stirrings of philosophical inquiry, ancient thinkers grappled with the fundamental composition of the world. They sought to identify the element or elements from which all things emerged, a quest that laid the groundwork for what we now call physics. Among the various candidates proposed, water consistently held a place of profound significance, not merely as a substance but as a principle embodying life, change, and the very nature of existence. This article explores the multifaceted role of water in ancient cosmological thought, tracing its journey from a singular originating element to a crucial component within more complex systems.

I. The Wet Beginning: Thales and the Arche of Water

The philosophical journey into the nature of reality often begins with Thales of Miletus, widely considered the first Western philosopher. Living in the 6th century BCE, Thales proposed a radical departure from mythological explanations, asserting that water was the fundamental arche, the originating substance from which all things are derived and into which they ultimately return.

Thales' Rationale for Water as the Primary Element:

- Ubiquity and Essentiality: Water is indispensable for life; all living things require it to survive.

- States of Matter: Thales observed water in its three states – liquid, solid (ice), and gas (vapor/mist) – suggesting its capacity to transform and embody different forms of matter.

- Nourishment and Growth: Seeds and plants grow in moisture, and even fire, though seemingly an opposing element, was thought to be nourished by water in some contexts.

- Support for the Earth: Thales is famously quoted as believing the Earth floats on water, much like a log.

This bold assertion marked a pivotal moment in intellectual history, shifting the focus from divine narratives to rational observation and the pursuit of a unified understanding of the world's physics. For Thales, the entire cosmos, in its myriad forms, was ultimately a manifestation of this single, primordial element.

II. Water in a Pluralistic Cosmos: Beyond Monism

While Thales championed water as the sole arche, subsequent pre-Socratic philosophers expanded the discussion, introducing other elements or principles. However, water maintained its crucial role within these evolving cosmological models.

- Empedocles' Four Roots: The Sicilian philosopher Empedocles (c. 494–434 BCE) proposed a system of four "roots" or elements: earth, air, fire, and water. These elements were eternal and unchangeable, combining and separating under the influence of two cosmic forces, Love and Strife, to form all the diverse phenomena of the world. In this model, water ceased to be the sole origin but remained an indispensable building block, interacting dynamically with the others.

- Anaxagoras' Seeds: Anaxagoras (c. 500–428 BCE) posited an infinite number of "seeds" or fundamental particles, each containing a portion of everything. While not a singular element like water, the process of mixture and separation, often involving moisture, was key to the formation of observable substances, with water playing a vital role in the initial cosmic mixture.

III. Platonic Forms and Aristotelian Physics: Classifying the Elements

The philosophical giants of Athens, Plato and Aristotle, further refined the understanding of elements, integrating water into their sophisticated metaphysical and physical systems.

A. Plato's Geometric Elements in the Timaeus

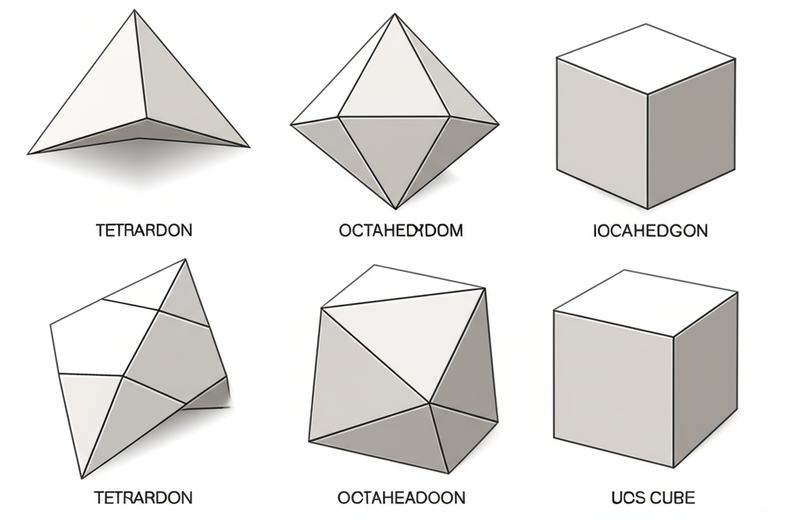

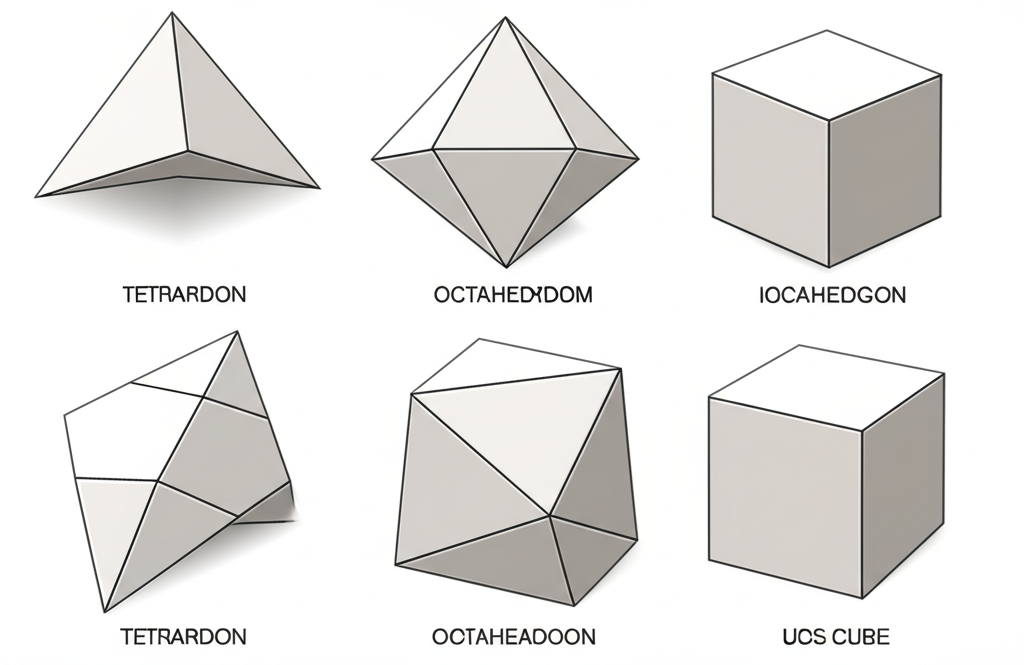

In his dialogue Timaeus, Plato presents a cosmology where the four fundamental elements (earth, air, fire, and water) are not merely substances but geometric forms constructed from basic triangles. This highly abstract approach connected the physics of the world to mathematical principles.

Plato's Elemental Geometries:

| Element | Platonic Solid | Base Triangles | Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fire | Tetrahedron | 24 | Sharp, mobile, penetrating |

| Air | Octahedron | 48 | Smooth, flowing |

| Water | Icosahedron | 120 | Mobile, easily divisible |

| Earth | Cube | 24 | Stable, immobile |

For Plato, water, represented by the icosahedron (a 20-faced polyhedron), possessed a specific structure that explained its properties of fluidity and its ability to transform into or be formed from other elements (except earth). This geometric understanding provided a rational, albeit highly conceptual, framework for the nature of matter.

B. Aristotle's Terrestrial Elements and Qualities

Aristotle (384–322 BCE), with his empirical approach, systematized the concept of four terrestrial elements (earth, air, fire, and water) based on their primary qualities: hot, cold, wet, and dry.

Aristotle's Elemental Qualities:

- Fire: Hot and Dry

- Air: Hot and Wet

- Water: Cold and Wet

- Earth: Cold and Dry

In Aristotle's Physics, these qualities determined the nature and behavior of each element. Water, being cold and wet, naturally moved downwards towards the center of the world (the Earth) and was crucial for the generation and corruption of all sublunary (below the moon) substances. It was the medium of life, moisture, and the basis for many transformations observed in the natural world. His comprehensive system dominated Western thought for over a millennium, firmly establishing water as one of the four essential building blocks of the terrestrial sphere.

arranged around a central sphere, with each solid clearly labeled with its corresponding element: fire, air, water, and earth, respectively. The background is a stylized cosmic void, hinting at the ancient Greek philosophical context.)

arranged around a central sphere, with each solid clearly labeled with its corresponding element: fire, air, water, and earth, respectively. The background is a stylized cosmic void, hinting at the ancient Greek philosophical context.)

IV. The Symbolic and Metaphysical Nature of Water

Beyond its role as a physical element, water also held profound symbolic and metaphysical significance in ancient thought, reflecting its intrinsic connection to life and change in the world.

- Flux and Change: Heraclitus' famous dictum, "You cannot step into the same river twice," perfectly encapsulates water's symbolic association with constant change, flux, and the impermanence of all things. Water served as a powerful metaphor for the dynamic nature of reality.

- Purification and Renewal: Its cleansing properties made water central to rituals of purification, baptism, and rebirth across various ancient cultures, signifying a spiritual renewal and the washing away of impurities.

- Life and Fertility: As the source of all life, water was often associated with fertility goddesses, creation myths, and the primordial chaos from which order emerged. The generative power of water was a universal theme.

- Depth and Mystery: The depths of the ocean represented the unknown, the subconscious, and the mysterious origins of life, often featuring in myths about sea monsters and hidden realms.

V. Conclusion: Water's Enduring Legacy in Our World View

From Thales' bold declaration of water as the sole arche to its precise geometric definition by Plato and its qualitative classification by Aristotle, the element of water has played an indispensable role in ancient cosmology. It served as a foundational concept in the development of physics, driving early inquiries into the nature of matter and the structure of the world. More than just a substance, water became a potent symbol of life, change, and the very essence of existence, shaping not only scientific understanding but also philosophical and spiritual perceptions. Its journey through ancient thought underscores humanity's persistent fascination with the fundamental elements that constitute our reality, a legacy that continues to influence our understanding of the cosmos and our place within it.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Thales of Miletus water arche philosophy"

2. ## 📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Plato Aristotle elements cosmology"