The Profound Distinction: Navigating the Waters Between Pleasure and Happiness

Summary: The philosophical landscape has long grappled with the fundamental distinction between pleasure and happiness. While often conflated in common parlance, these two states represent profoundly different human experiences and aspirations. Pleasure is typically understood as a fleeting, sensory, often immediate gratification, intrinsically linked to the absence of pain and the satisfaction of desire. Happiness, conversely, is a more enduring, profound state of well-being, often associated with a life well-lived, moral virtue, intellectual flourishing, and a sense of purpose that transcends mere momentary gratification. Understanding this crucial difference is not merely an academic exercise; it is essential for charting a course towards a truly fulfilling existence.

Unpacking the Definitions: What Are We Truly Seeking?

From the earliest inquiries into the human condition, philosophers have sought to define the good life. Central to this quest is an examination of what truly brings us satisfaction. Is it the thrill of a new experience, the relief from discomfort, or something deeper and more lasting?

The Immediate Allure of Pleasure

Pleasure, in its most common definition, refers to a sensation or feeling of enjoyment, satisfaction, or delight, often arising from a particular activity, object, or sensory experience. It is the taste of a fine meal, the warmth of a fire on a cold night, the joy of physical intimacy, or the temporary relief from a nagging worry.

Philosophers across the ages, from the Hedonists to Epicurus, recognized the undeniable power of pleasure and pain as primary motivators of human action. Epicurus, for instance, famously posited that the highest good was pleasure, though he clarified this not as sensual indulgence, but as ataraxia (freedom from mental disturbance) and aponia (absence of physical pain) – a state of tranquil contentment. Yet, even in this refined view, pleasure retains its character as a state achieved through the alleviation of negative sensations or the presence of agreeable ones.

Key characteristics of pleasure include:

- Transience: It is often momentary, waxing and waning with the stimuli that produce it.

- Sensory Basis: Frequently tied to our physical senses or immediate emotional responses.

- Reactive Nature: Often a response to a specific event or the satisfaction of a particular desire.

- Intensity: Can range from mild contentment to intense euphoria, but its intensity doesn't necessarily dictate its lasting impact.

The Enduring Quest for Happiness

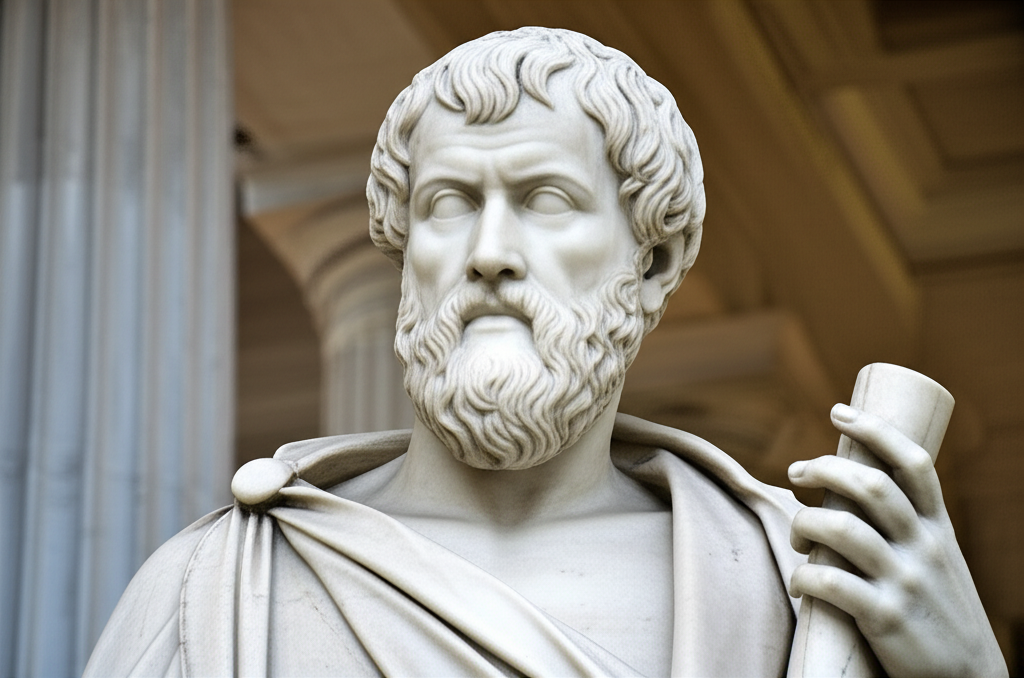

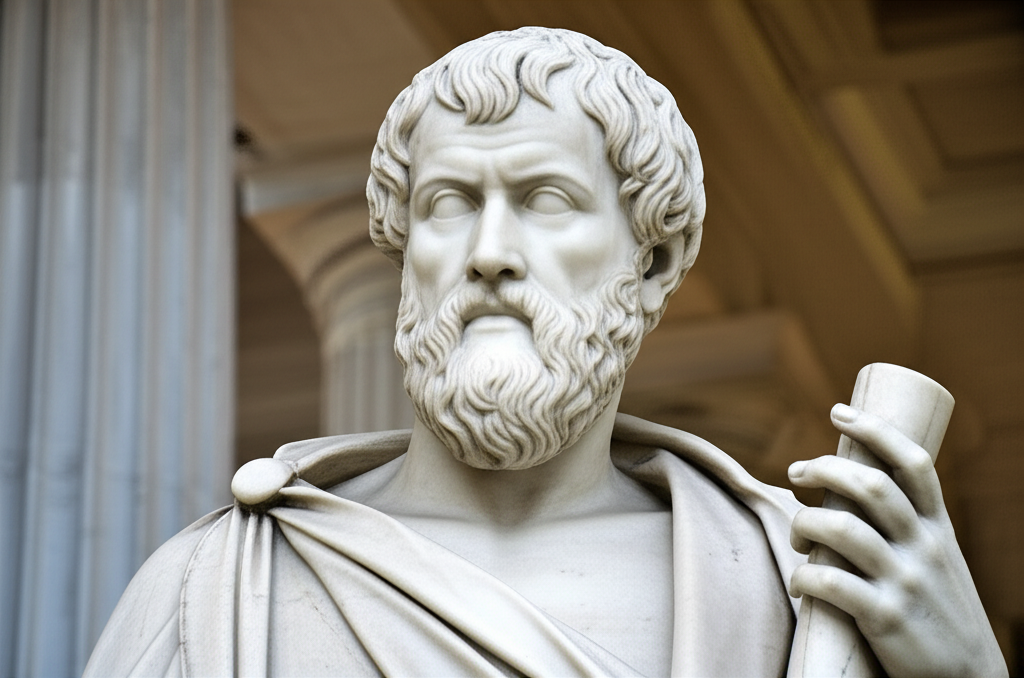

Happiness, on the other hand, presents a far more complex and enduring definition. It is not merely a collection of pleasant moments, but rather an overarching state of flourishing, contentment, and deep satisfaction with one's life as a whole. For Aristotle, in his Nicomachean Ethics, happiness (or eudaimonia) was the ultimate human good, the highest aim of all human activity. It was not a feeling, but an activity of the soul in accordance with virtue over a complete life.

Aristotle's conception of eudaimonia moves far beyond simple pleasure. It demands:

- Virtuous Activity: Living in accordance with reason and moral excellence.

- Intellectual Contemplation: Engaging with profound truths and knowledge.

- Purpose and Meaning: A sense of direction and contribution to something greater than oneself.

- Endurance: It is a stable, long-term condition, not easily swayed by momentary misfortunes.

This understanding is echoed in various forms throughout the Great Books of the Western World, from Plato's discussions of the well-ordered soul in The Republic to the Stoic emphasis on virtue and wisdom as the path to tranquility.

The Crucial Distinction: A Tale of Two States

The very essence of the distinction lies in their nature, duration, and the means by which they are typically achieved. To mistake one for the other is to fundamentally misdirect our life's efforts.

| Feature | Pleasure | Happiness |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | Sensory, emotional, immediate, often reactive | Intellectual, moral, enduring, holistic, active |

| Duration | Fleeting, transient, momentary | Stable, long-term, sustained over a lifetime |

| Source | External stimuli, satisfaction of desires | Internal disposition, virtuous activity, purpose |

| Goal | Gratification, relief from pain | Flourishing, fulfillment, living well |

| Dependence | Highly dependent on external circumstances | Less dependent on external circumstances |

| Relationship | Can contribute to happiness, but not sufficient; can also detract from it | Encompasses and elevates positive experiences; prioritizes long-term well-being |

Consider the person who pursues an endless stream of sensory delights – lavish meals, constant entertainment, fleeting relationships. While these may provide bursts of pleasure, they often fail to coalesce into a coherent, meaningful life. Indeed, an unbridled pursuit of pleasure can lead to anhedonia, a state where the capacity for joy diminishes, or even to dissatisfaction and despair, as the next thrill always proves insufficient.

True happiness, conversely, is often found in the demanding work of building a career, nurturing deep relationships, contributing to one's community, or mastering a challenging skill. These activities may involve moments of discomfort or effort, moments that are certainly not pleasurable in the immediate sense, but they contribute to a profound, lasting sense of accomplishment and fulfillment that defines a happy life.

Why This Distinction Matters

The ability to discern between pleasure and happiness is perhaps one of the most vital philosophical tools we can possess. It empowers us to make conscious choices about what we truly value and how we allocate our time and energy.

- Guiding Our Choices: If our primary aim is merely pleasure, we might prioritize instant gratification, often at the expense of future well-being. If our aim is happiness, we are more likely to make choices that require discipline, patience, and effort, knowing they contribute to a greater, more enduring good.

- Resilience in Adversity: A life built on the pursuit of happiness, understood as eudaimonia, allows for resilience in the face of pain and adversity. While unpleasant experiences are inevitable, they do not necessarily undermine a person's overall happiness if their foundation is rooted in virtue and purpose.

- Defining the Good Life: Ultimately, this distinction helps us to define what constitutes a truly good and meaningful life. It challenges us to look beyond superficial satisfactions and to engage with the deeper questions of existence, purpose, and human flourishing.

To live well, then, is not simply to accumulate pleasant sensations, but to cultivate a character and a life that allows for genuine, lasting happiness. It is to understand that while pleasure can be a welcome companion on the journey, it is never the destination itself.

YouTube:

- "Aristotle's Ethics: Eudaimonia and the Virtuous Life"

- "The Philosophy of Epicurus: Pleasure, Pain, and Tranquility"

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "The Distinction Between Pleasure and Happiness philosophy"