Untangling the Threads: The Distinction Between Art and Beauty

Summary: While often intertwined in common discourse, Art and Beauty are distinct philosophical concepts. Art is fundamentally a human creation, an intentional act of making or expressing, which may or may not possess beauty. Beauty, conversely, is a perceived quality or characteristic that evokes pleasure, admiration, or a sense of harmony, and can exist independently in nature, mathematics, or even in ideas, without any human artistic intervention. Understanding this distinction enriches our appreciation for both human creativity and the inherent aesthetic dimensions of the world.

Introduction: A Necessary Separation

For centuries, philosophers, artists, and everyday observers have grappled with the concepts of Art and Beauty. It's a natural inclination to link them—after all, much of what we deem "art" we also consider "beautiful." Yet, to conflate the two is to miss a crucial philosophical nuance, one that has been carefully delineated by thinkers from Plato to Kant. To truly appreciate the depth of human expression and the profound nature of aesthetic experience, we must first establish a clear definition for each, recognizing their unique properties and their often-independent existences.

Defining Our Terms: What is Art?

At its core, Art is a product of human endeavor. It is the conscious application of skill and imagination to create objects, environments, or experiences. From the ancient Greek concept of techne, referring to craft or skill, to contemporary performance art, the essence of art lies in its intentionality and its creation by human hands or minds.

- Human Agency: Art is always made. Whether it's a sculpted figure, a written symphony, a painted canvas, or a conceptual installation, a human being is the progenitor.

- Expression and Communication: Art serves as a vehicle for ideas, emotions, narratives, or observations. It can imitate reality (Aristotle's mimesis), challenge norms, or simply exist as a pure aesthetic form.

- Skill and Craft: The quality of art often relates to the mastery of its medium, the ingenuity of its conception, or the impact it has on its audience.

- Variety of Forms: Art encompasses painting, sculpture, music, literature, dance, architecture, and countless other disciplines, each with its own conventions and possibilities.

Crucially, art does not require beauty to be art. A stark, disturbing painting, a piece of music designed to evoke discomfort, or a play that confronts difficult truths are all undeniably art, yet they may not be conventionally beautiful. Their value as art is derived from their expressive power, their conceptual depth, or their capacity to provoke thought and feeling, rather than solely from their aesthetic pleasantness.

Defining Our Terms: What is Beauty?

Beauty, by contrast, is a perceived quality or characteristic that evokes a sense of pleasure, delight, or admiration in the beholder. It's an aesthetic experience that can transcend human creation, appearing naturally in the world around us.

- Perceived Quality: Beauty is often described as a sensory experience, a feeling of satisfaction or harmony. It can be found in the visual (a sunset), the auditory (a bird's song), or even the intellectual (the elegance of a mathematical proof).

- Objective vs. Subjective Debate: Philosophers have long debated whether beauty is an objective property of an object (Plato's Ideal Forms of Beauty) or a subjective experience of the observer ("Beauty is in the eye of the beholder," as Hume might suggest). Kant attempted a synthesis, proposing a "disinterested pleasure" that hints at a universal human capacity to appreciate certain aesthetic forms.

- Natural Occurrence: Beauty exists abundantly in nature – the intricate pattern of a snowflake, the grandeur of a mountain range, the symmetry of a flower. These are beautiful without any human intervention.

- Evokes Pleasure: A core aspect of beauty is the positive emotional or intellectual response it elicits. This pleasure is often described as pure, unadulterated, and intrinsically valuable.

The quality of beauty is often associated with harmony, proportion, integrity, and a certain radiance or clarity that makes an object compelling.

The Crucial Distinction: Art vs. Beauty

To clarify, let's delineate the fundamental differences between these two concepts:

| Feature | Art | Beauty |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Human-made; product of skill, intention, and imagination | Can be natural or human-made; a perceived quality |

| Nature | A noun; a category of human creation | A noun or adjective; a characteristic or attribute |

| Requirement | Requires a creator/maker | Requires a beholder/perceiver to be recognized, but exists independently |

| Purpose | To express, communicate, provoke, imitate, decorate | To evoke pleasure, admiration, harmony, or delight |

| Aesthetic Value | Not necessarily beautiful; can be disturbing, ugly, or conceptual | Inherently positive aesthetic value; almost always associated with pleasure |

| Existence | Exists as a physical object, performance, or concept | Exists as a perceived quality of an object or experience |

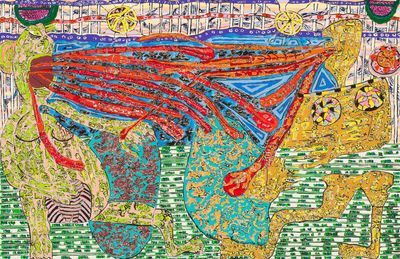

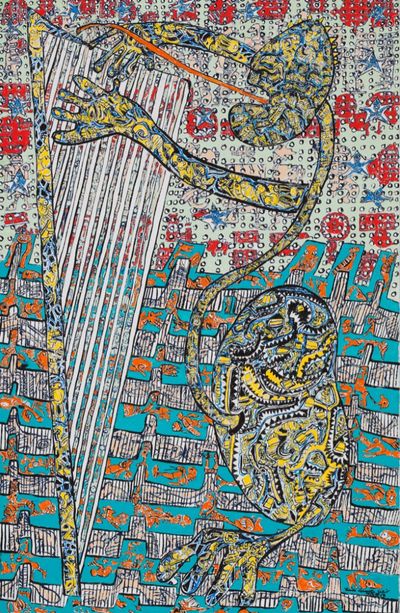

(Image: A classical Greek marble statue of Venus, perfectly proportioned and serene, stands beside a stark, abstract modern sculpture made of rusted metal and jagged edges. Both are clearly art, but only the Venus embodies conventional beauty, highlighting the distinction.)

The Interplay: When They Meet (and When They Don't)

While distinct, art and beauty frequently converge. Much of human art strives for beauty, employing principles of harmony, proportion, and form to create works that are aesthetically pleasing. Think of the perfect symmetry in a Renaissance painting or the lyrical flow of a Shakespearean sonnet. Here, beauty is a desired quality that elevates the art.

However, art can also deliberately eschew conventional beauty. Conceptual art may prioritize an idea over aesthetics. Protest art might aim to shock rather than soothe. The sublime, a concept explored by thinkers like Edmund Burke, describes experiences that are awe-inspiring and even terrifying, pushing beyond mere beauty. In these instances, the quality of the art is judged not by its beauty, but by its power, its originality, or its capacity to challenge.

Philosophical Perspectives on Quality

When we discuss the quality of art or beauty, we enter another rich philosophical domain.

- Quality in Art: The assessment of artistic quality often involves examining the artist's skill, the originality of the concept, the emotional or intellectual impact, and the work's coherence or integrity. For Aristotle, the quality of a tragedy depended on its plot, character, thought, diction, song, and spectacle, all contributing to its capacity to evoke catharsis.

- Quality in Beauty: The quality of beauty, as perceived, might relate to its universality (does it appeal to many?), its purity, or its capacity to evoke a "disinterested pleasure" as Kant described – pleasure derived from the form of the object itself, rather than from any personal interest or utility. Plato linked beauty to truth and goodness, suggesting a higher, more ideal quality of beauty that transcends the material world.

Conclusion: A Richer Understanding

By carefully distinguishing between Art and Beauty, we gain a more nuanced and profound appreciation for both. Art stands as a testament to the boundless creativity and expressive capacity of humanity, a realm where intention, skill, and concept reign supreme. Beauty, whether found in a meticulously crafted symphony or a naturally occurring rainbow, speaks to a fundamental aesthetic dimension of existence, capable of evoking deep pleasure and wonder. Recognizing that art can exist without beauty, and beauty without art, liberates us to engage with each concept on its own terms, leading to a richer, more expansive philosophical journey.

**## 📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Theory of Beauty" or "Kant's Aesthetics Explained""**