The Distinction Between Art and Beauty: A Philosophical Unpacking

It's a common misconception, isn't it? To hear "art" and immediately think "beauty." While the two are often intertwined, the philosophical journey through the definition and quality of each reveals a crucial, often overlooked, distinction. Simply put: Art is a human creation, an act of making and expressing, while beauty is a perceived quality that evokes pleasure or admiration. They are related, certainly, but not synonymous. Understanding this fundamental difference allows us to appreciate both with greater depth and clarity.

The Core Divide: What Are We Talking About?

To navigate this philosophical landscape, we must first establish clear boundaries for our terms. Without a precise definition, our discussions risk becoming muddled.

Defining Our Terms: Art and Beauty

- Art: At its core, Art is the product of human skill, imagination, and intention. It is a creative act, a means of expression, communication, or representation. Whether it's a painting, a symphony, a sculpture, a poem, or a piece of architecture, art fundamentally involves a creator and a deliberate act of making. It's about what we do and what we produce.

- Beauty: In contrast, Beauty is a quality that, when perceived, evokes a sense of pleasure, admiration, or intellectual satisfaction. It can be found in the harmonious arrangement of parts, in striking visual forms, in the elegance of an idea, or in the profound resonance of a natural phenomenon. Beauty is often subjective, residing in the eye of the beholder, yet philosophers from Plato to Kant have grappled with whether it possesses an objective, universal dimension.

Art: The Act of Creation and Intention

When we speak of Art, we are speaking of an artifact, a deliberate human endeavor. The existence of art presupposes an artist, a medium, and a concept or intention. A cave painting, a Shakespearean sonnet, a Bach fugue—all are manifestations of human agency. Their quality as art stems from their craft, their originality, their communicative power, or their ability to provoke thought and emotion.

Consider the diverse forms art takes:

- Visual Arts: Painting, sculpture, photography, film.

- Performing Arts: Music, dance, theatre.

- Literary Arts: Poetry, prose, drama.

- Applied Arts: Architecture, design, craft.

Each of these fields requires skill, creativity, and a conscious act of production. The purpose of art can be varied: to tell a story, to express an emotion, to challenge societal norms, to create a functional object, or simply to explore aesthetic possibilities. What remains constant is its origin in human will.

Beauty: A Perceived Quality and Experience

Beauty, on the other hand, is a characteristic, a quality that can be attributed to objects, ideas, or experiences. It is not necessarily created by humans; a sunset, a mountain range, or the intricate pattern of a snowflake can be profoundly beautiful. When we encounter beauty, we often experience a sense of delight, wonder, or profound connection.

Philosophers throughout the Great Books of the Western World have debated the nature of beauty:

- Plato saw Beauty as an eternal, ideal Form, independent of human perception, existing in a realm beyond our senses. Our experience of beautiful things on Earth was merely a glimpse or a recollection of this perfect Form.

- Aristotle linked beauty to order, symmetry, and definiteness, often within the context of art (especially tragedy), where these qualities contributed to the artwork's effectiveness and pleasure.

- Immanuel Kant, in his Critique of Judgment, argued that our judgment of beauty is subjective but also holds a "subjective universality." We feel that others ought to find beautiful what we find beautiful, even if there's no objective rule for it. This "disinterested pleasure" is central to his definition of aesthetic experience.

The experience of beauty is often deeply personal, yet there are also widely shared perceptions of what is beautiful. This duality forms the heart of its philosophical intrigue.

| Aspect | Art | Beauty |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | Human creation, artifact | Perceived quality, characteristic |

| Origin | Intentional act, skill, imagination | Inherent (nature) or attributed (subjective) |

| Requirement | Creator, medium, concept | Observer, sensory/intellectual perception |

| Purpose | Expression, communication, function | Evoking pleasure, admiration, harmony |

| Existence | Exists as an object/performance | Exists as an experience/judgment |

The Overlap and Divergence: Where They Meet and Part Ways

The profound connection between Art and Beauty is undeniable. Much of humanity's artistic output strives for beauty, and many of the most celebrated artworks are indeed beautiful. A Michelangelo sculpture, a Mozart symphony, or a classical Greek temple all exemplify art that embodies a high quality of beauty.

However, it is crucial to recognize their divergence:

-

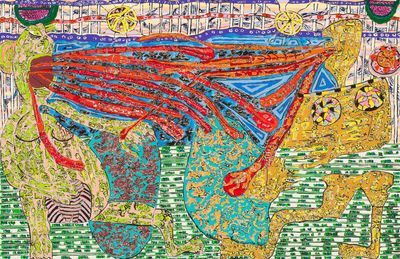

Art does not have to be beautiful. Some of the most impactful and thought-provoking art deliberately shuns conventional beauty. It might be challenging, disturbing, ugly, or even grotesque, yet it remains powerful art. Think of Picasso's Guernica, which depicts the horrors of war, or certain conceptual pieces designed to provoke rather than please. The intent is not necessarily to create something aesthetically pleasing but to communicate, question, or evoke a strong, perhaps uncomfortable, response.

(Image: An oil painting depicting a stark, angular cityscape under a stormy, bruised sky. The colors are muted grays, deep blues, and hints of dull red, evoking a sense of unease rather than traditional aesthetic pleasure. The brushstrokes are visible and forceful, emphasizing the artificiality and harshness of the urban environment.)

This painting, while undoubtedly a work of art, does not necessarily aim for traditional beauty. Its power lies in its ability to convey a mood, a critique, or a feeling of desolation.

-

Beauty can exist without art. As mentioned, natural phenomena like a perfectly formed crystal, the intricate design of a seashell, or the vastness of a starry night sky can be profoundly beautiful without being the product of human artistic endeavor. Similarly, a mathematical proof can possess an elegant beauty in its simplicity and logic, independent of any artistic intent.

The Philosophical Journey: From Plato to Kant

The distinction between Art and Beauty has been a fertile ground for philosophical inquiry for millennia. From Plato's hierarchical view of ideal beauty separate from earthly imitations, to Aristotle's analysis of art as mimesis (imitation) that can reveal universal truths, to Kant's exploration of aesthetic judgment as a unique faculty of the mind—each era has contributed to our understanding.

These thinkers, whose works form the backbone of the Great Books of the Western World, compel us to look beyond superficial connections. They challenge us to understand that while art often seeks beauty, and beauty often finds its expression in art, their underlying definitions and essential qualities remain distinct.

Conclusion

The distinction between Art and Beauty is more than an academic exercise; it's a doorway to a richer appreciation of the world. Recognizing that art is a human act of creation and expression, while beauty is a perceived quality that can exist both within and outside of art, liberates us. It allows us to admire a beautiful sunset without needing an artist, and to be deeply moved by a challenging artwork that makes no claim to conventional beauty. This nuanced understanding enriches our encounters with both the masterpieces of human ingenuity and the wonders of the natural world.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Theory of Beauty philosophy""

📹 Related Video: KANT ON: What is Enlightenment?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Kant Aesthetics Art vs Beauty explained""