The Nuanced Tapestry: Distinguishing Art from Beauty

Often, in our daily conversations, the terms "art" and "beauty" are used interchangeably, as if one inherently implies the other. We might exclaim, "That painting is so beautiful, it's true art!" or dismiss a challenging piece with "It's not beautiful, so it can't be art." However, to conflate these two profound concepts is to miss a crucial philosophical distinction that enriches our understanding of both human creation and aesthetic experience. Simply put, art is a product of human intention and skill, while beauty is a quality that evokes pleasure or admiration, found in both the natural world and human artifacts. While much art strives for beauty, and beauty can certainly elevate a work of art, neither is a prerequisite for the other.

Unraveling the Threads: Defining Our Terms

To truly appreciate the unique contributions of art and beauty to our lives, we must first establish clear definitions. This is not merely an academic exercise but a foundational step towards a more sophisticated engagement with our world.

What is Art?

The definition of art has been a subject of intense philosophical debate for millennia, from the mimesis (imitation) of Aristotle to the institutional theories of modern times. For our purposes, we can broadly understand art as:

- Human Creation: Art is fundamentally a product of human agency, skill, and intellect. It is something made or performed by people.

- Intentionality: It typically involves a conscious act of creation, expression, or communication on the part of the artist. This intent can be to provoke, to document, to challenge, to entertain, or even to mystify.

- Skill and Technique: Often, though not always, art involves the application of learned skills or innovative techniques (what the Greeks called techne).

- Expression and Meaning: Art serves as a vehicle for ideas, emotions, narratives, or abstract concepts, inviting interpretation and engagement from its audience.

Art, therefore, is an act of making, a form of human endeavor that transforms raw materials or abstract ideas into something new and expressive. Its quality can be judged by its originality, craftsmanship, emotional impact, intellectual depth, or its ability to challenge perceptions.

What is Beauty?

Beauty, on the other hand, is generally understood as:

- A Quality of Perception: Beauty is a characteristic or set of characteristics that, when perceived, evokes a feeling of pleasure, satisfaction, or admiration in the observer.

- Sensory and Intellectual Appeal: It can appeal to our senses (sight, sound, touch) through harmony, proportion, color, form, or rhythm, but also to our intellect through elegance, truth, or moral goodness.

- Subjectivity vs. Objectivity: Philosophers like Plato spoke of Beauty as an eternal Form, an objective ideal. Later thinkers, notably David Hume and Immanuel Kant, emphasized the subjective nature of aesthetic judgment, though Kant also sought universal principles underlying our judgments of taste.

- Ubiquitous Presence: Beauty is not confined to human creations; it is found abundantly in the natural world—a sunset, a mathematical equation, the intricate pattern of a snowflake, the grace of an animal.

Beauty is thus a quality—a property of an object or experience—that elicits a particular kind of positive aesthetic response. Its presence is often a source of profound joy and wonder.

The Nature of Art: Beyond Mere Aesthetics

Art's domain extends far beyond the pursuit of pleasant aesthetics. While a beautiful object might be art, an object need not be beautiful to be art. Consider:

- Protest Art: Designed to provoke anger or discomfort, such as Goya's The Disasters of War.

- Conceptual Art: Prioritizes ideas over visual appeal, like Marcel Duchamp's Fountain.

- The Grotesque: Art that deliberately depicts the ugly, distorted, or horrifying to make a point or explore the human condition.

- Challenging Art: Works that push boundaries, question norms, or depict difficult truths, often intentionally unsettling rather than pleasing.

In these instances, the art lies in the creation, the concept, the skill of execution, and the message conveyed, irrespective of—or even in direct opposition to—traditional notions of beauty. The quality of such art is judged not by its ability to charm the eye, but by its power to stimulate thought, evoke emotion, or represent a particular perspective.

The Nature of Beauty: An Independent Phenomenon

Beauty, conversely, can exist entirely independent of human intervention or artistic intent.

- Natural Wonders: A majestic mountain range, the intricate patterns of a seashell, the vibrant colors of a coral reef—these possess intrinsic beauty that predates and transcends human artistry.

- Abstract Concepts: The elegance of a scientific theory, the perfect symmetry of a mathematical proof, or the moral rectitude of an action can be described as beautiful, appealing to our intellect rather than our senses.

- Everyday Objects: A perfectly formed fruit, the sheen of polished wood, or the simple utility of a well-designed tool can evoke a sense of beauty without necessarily being considered "art."

This table highlights the key differentiators:

| Feature | Art | Beauty |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Human creation, intention, skill | Intrinsic quality, perceived attribute |

| Primary Nature | An act, a process, an artifact | A sensation, a feeling, a judgment |

| Existence | Requires human agency | Can exist independently (e.g., in nature) |

| Purpose/Effect | To express, communicate, challenge | To evoke pleasure, admiration, awe |

| Relationship | Can possess beauty, but not necessarily | Can be found in art, but also elsewhere |

Where They Intersect (and Diverge)

The intersection of art and beauty is vast and rich. Much art does aim for beauty, whether through harmonious composition, evocative color, or graceful form. A Renaissance fresco, a classical symphony, or an exquisitely crafted piece of jewelry all exemplify art that embodies beauty. In these cases, beauty enhances the artistic experience, drawing us in and offering a particular kind of aesthetic pleasure.

However, the divergence is equally significant:

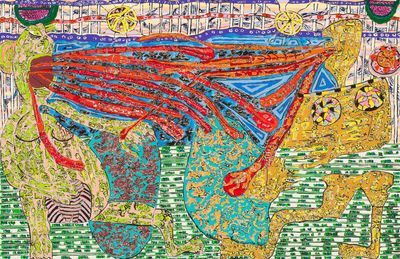

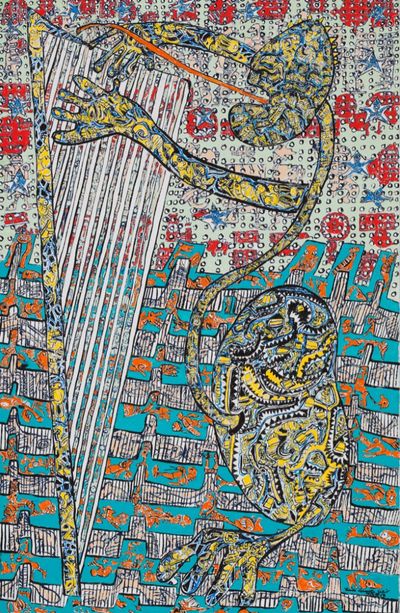

- Art without Beauty: Think of a raw, powerful expressionist painting, a jarring piece of avant-garde music, or a brutalist architectural structure. These are undeniably art, demonstrating human creativity and intention, but they may not conform to conventional standards of beauty. Their quality is measured by their impact, their innovation, or their truthfulness, rather than their pleasing appearance.

- Beauty without Art: A breathtaking sunset, the intricate structure of a spiderweb, or the simple elegance of a naturally occurring crystal are all profoundly beautiful, yet they are not "art" in the sense of being a deliberate human creation.

(Image: A split image. On the left, a detailed, high-resolution photograph of a pristine, naturally occurring geode with shimmering crystal formations, emphasizing its inherent, untouched beauty. On the right, a stark, abstract expressionist painting with bold, clashing colors and aggressive brushstrokes, conveying raw emotion and artistic intent, challenging traditional notions of beauty.)

Why the Distinction Matters

Understanding the separate definition and quality of art and beauty is not merely an academic exercise; it profoundly impacts how we engage with the world:

- Broader Appreciation of Art: It allows us to appreciate art that is challenging, disturbing, or unconventional, recognizing its artistic merit even if it doesn't conform to our aesthetic preferences for beauty. We can ask, "Is it effective art?" rather than just, "Is it beautiful?"

- Richer Aesthetic Experience: It enables us to find beauty in unexpected places—in the natural world, in scientific principles, in acts of kindness—without needing to categorize them as "art."

- Critical Thinking: It sharpens our critical faculties, allowing us to analyze a work of art based on its intent, execution, and impact, rather than solely on its pleasing appearance. This is vital for understanding complex philosophical and cultural expressions.

- Understanding Human Creativity: It highlights the diverse motivations behind human creation. Artists don't always create to make something beautiful; they create to explore, to question, to document, to communicate.

Conclusion: A More Expansive View

The distinction between art and beauty invites us to embrace a more expansive and nuanced understanding of our aesthetic experiences. Art, as a testament to human ingenuity and expression, can encompass a vast spectrum of forms and intentions, not all of which are designed to be beautiful. Beauty, as a fundamental quality of existence, can grace both the natural and the artificial, evoking pleasure and wonder in countless manifestations. By recognizing that art is the making and beauty is the perceiving of a pleasing quality, we unlock a deeper appreciation for the intricate tapestry of human culture and the sublime wonders of the world around us.

YouTube Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Theory of Forms and Beauty Explained""

-

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""What is Art? Philosophy of Art Introduction""