The Distinction Between Art and Beauty: A Philosophical Unpacking

Summary: More Than Meets the Eye

Often, the terms "art" and "beauty" are used interchangeably, as if one inherently implies the other. However, a deeper philosophical dive reveals a crucial distinction: Beauty is primarily an aesthetic quality or experience, often evoking pleasure and admiration, whether found in nature or human creation. Art, on the other hand, is a human endeavor, a definition of a creative act or its product, which may or may not possess beauty as its primary characteristic or even at all. Understanding this separation allows for a richer appreciation of both the world around us and the vast landscape of human expression.

Beauty: An Intrinsic Quality or a Subjective Experience?

When we speak of beauty, we are often referring to a particular quality that evokes a profound sensory or intellectual pleasure. This quality can manifest in countless forms: the symmetry of a snowflake, the harmony of a musical chord, the elegance of a mathematical proof, or the captivating grace of a dancer. From the ancient Greek philosophers, as explored in the Great Books of the Western World, beauty was often linked to notions of truth, goodness, and divine order—a reflection of perfect Forms. Plato, for instance, posited a transcendent Form of Beauty, which earthly beautiful objects merely imperfectly imitate.

However, the experience of beauty is also profoundly subjective. What one person finds beautiful, another might not. Is beauty, then, entirely "in the eye of the beholder," or are there universal principles that underpin its perception? This enduring debate highlights the multifaceted nature of beauty: it is both a perceived quality and a deeply personal response. Regardless, its essence lies in its capacity to move, to inspire, and to please.

Art: Intentional Creation and Broad Definition

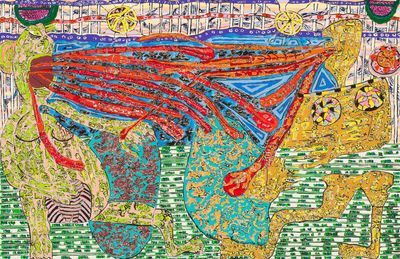

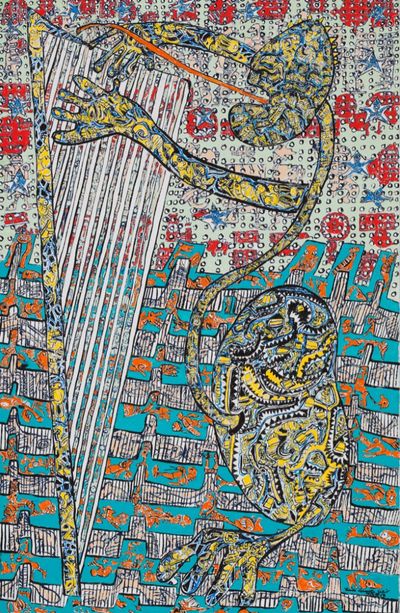

Art, by contrast, is fundamentally a human activity—a conscious act of creation, expression, or communication. It is a category of human artifacts and performances that are made with an intention to engage the senses, intellect, or emotion, often to convey an idea, narrative, or feeling. The definition of what constitutes art has evolved dramatically throughout history. While classical art often aimed for mimesis (imitation of nature) and beauty, the 20th century saw a radical expansion, embracing works that challenge, provoke, or even disgust.

Consider Marcel Duchamp's "Fountain," a urinal presented as sculpture. Its intention was not to be beautiful, but to question the very definition of art and the role of the artist. Here, the quality of beauty is irrelevant; the conceptual impact is paramount. Art is about the making, the meaning, and the context, extending far beyond mere aesthetics.

Navigating the Overlap and Divergence

The relationship between art and beauty is complex and often intertwined, yet distinct.

| Feature | Beauty | Art |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | A perceived quality or aesthetic experience | A human endeavor, creation, or definition |

| Source | Can be natural or man-made | Always man-made (or human-directed) |

| Purpose | To evoke pleasure, admiration, harmony | To express, communicate, challenge, explore |

| Necessity | Not required for something to be art | Does not necessarily need to be beautiful |

| Evaluation | Often subjective, based on aesthetic appeal | Based on intent, execution, impact, context |

While much art strives for beauty, and beautiful objects can certainly be art, the two are not mutually dependent. A breathtaking sunset is beautiful but not art. A challenging, dissonant musical composition might be considered profound art, yet few would describe it as "beautiful" in the conventional sense.

Historical Echoes: From Plato to Postmodernism

The Great Books provide ample context for this distinction. Early philosophers like Plato and Aristotle, in works such as The Republic and Poetics, often conflated beauty with artistic excellence, seeing art as an imitation that ideally reflects perfect forms or achieves harmonious structure. Beauty was a key quality of good art.

However, later thinkers began to disentangle these concepts. Immanuel Kant, in his Critique of Judgment, distinguished between the "beautiful" and the "sublime," and emphasized the "disinterested pleasure" derived from beauty, separating it from utility or moral goodness. Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, in his Lectures on Aesthetics, viewed art as a manifestation of the Absolute Spirit, arguing that its purpose was not merely to be beautiful but to reveal truth through sensory forms. This trajectory paved the way for modern and postmodern art, where the definition of art expanded dramatically, often prioritizing conceptual impact, social commentary, or emotional resonance over traditional notions of aesthetic quality.

Why This Distinction Resonates

Recognizing the distinction between art and beauty liberates our understanding of both. It allows us to appreciate the intrinsic splendor of the natural world without needing to categorize it as art. Crucially, it broadens our acceptance and critical engagement with art itself, freeing it from the narrow confines of conventional prettiness. Art can be unsettling, provocative, challenging, or merely observational, and still be profoundly significant. By separating the quality of beauty from the definition of art, we open ourselves to a richer, more diverse, and more intellectually stimulating engagement with human creativity in all its forms.

**## 📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Philosophy of Art vs Beauty Explained""**

**## 📹 Related Video: KANT ON: What is Enlightenment?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""The Problem of Defining Art""**