The Distinction Between Aristocracy and Monarchy: A Philosophical Inquiry

From the ancient city-states of Greece to the sprawling empires of antiquity, the fundamental questions of governance have perpetually occupied the finest minds. Among these, the distinctions between different forms of rule are paramount, particularly the often-confused concepts of aristocracy and monarchy. While both can represent a concentration of power, their underlying principles, justifications, and potential for virtue or corruption diverge significantly. This article, drawing heavily from the enduring wisdom contained within the Great Books of the Western World, aims to clarify these crucial differences, revealing how the definition of who rules, and why, shapes the very nature of a government.

Unpacking the Foundations of Political Power

To truly grasp the subtle yet profound differences between aristocracy and monarchy, we must first return to their etymological roots and the philosophical frameworks laid down by thinkers like Plato and Aristotle. These ancient philosophers meticulously categorized forms of government, not merely by the number of rulers, but by their purpose and character.

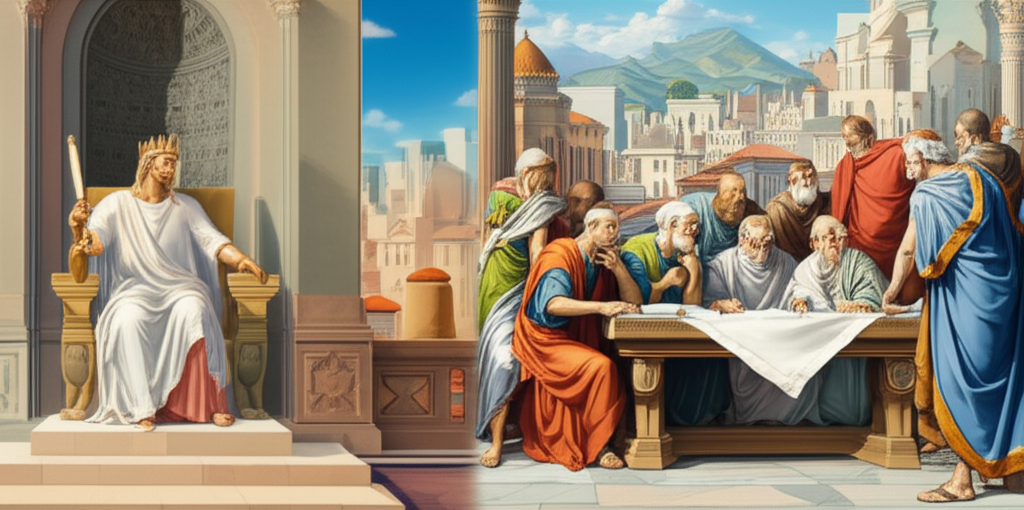

The Sovereign's Crown: Understanding Monarchy

Monarchy, derived from the Greek monos (single) and archein (to rule), is a form of government characterized by the rule of a single individual. This singular ruler, the monarch, often holds supreme authority, which can be absolute or constitutionally limited.

- Definition: Rule by one person.

- Key Characteristics:

- Singular Authority: Power is vested in one individual.

- Succession: Often hereditary, passing down through a royal lineage, but can also be elective.

- Legitimacy: Historically derived from divine right, tradition, or conquest.

- Virtuous Form: According to Aristotle, a true monarchy aims at the common good, with the monarch acting as a wise and benevolent leader.

- Corrupted Form: Tyranny, where the single ruler governs solely for their own self-interest, often through oppression.

The ideal monarch, as envisioned in some classical texts, is a philosopher-king, a paragon of wisdom and justice, whose singular virtue guides the state. However, the inherent risk, as history repeatedly demonstrates, is the descent into tyranny, where unchecked power corrupts even the most well-intentioned.

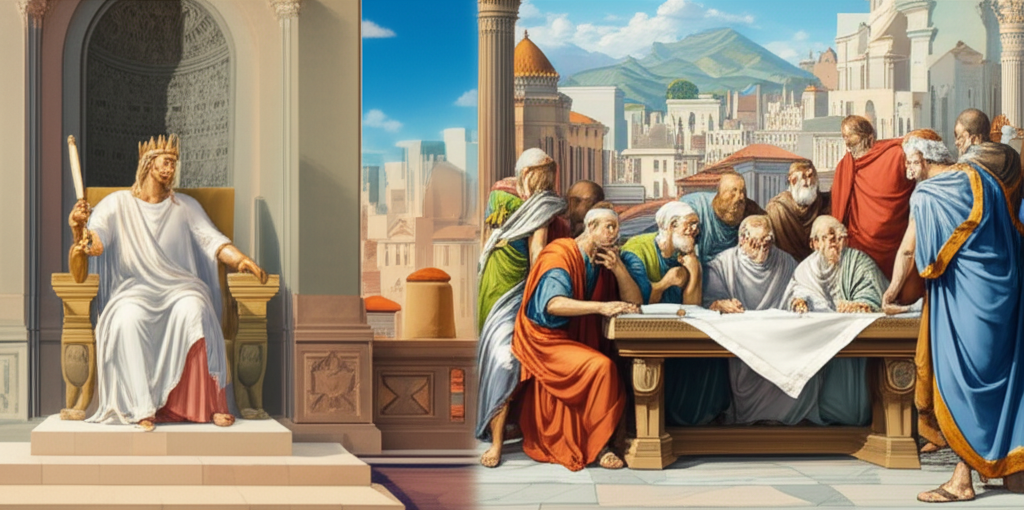

The Rule of the Virtuous: Unpacking Aristocracy

Aristocracy, originating from the Greek aristoi (best) and kratos (power/rule), signifies a form of government where power is held by a select group of individuals identified as the "best." Crucially, this "best" does not necessarily imply wealth or lineage, but rather a superior quality – be it wisdom, virtue, military prowess, or a combination thereof.

- Definition: Rule by the "best" or a select few.

- Key Characteristics:

- Collective Authority: Power is shared among a small, elite group.

- Selection Basis: Ideally, rulers are chosen based on merit, education, moral excellence, or exceptional skill. It is not inherently hereditary, though historically, inherited status often coincided with perceived "best" qualities.

- Legitimacy: Derived from the perceived superior qualities and wisdom of the ruling class, acting in the collective interest.

- Virtuous Form: A true aristocracy aims at the common good, with the "best" guiding the state through their wisdom and virtue.

- Corrupted Form: Oligarchy, where the few rule for their own self-interest, typically based on wealth, birth, or military power, rather than genuine merit.

Plato's Republic, for instance, posits an ideal state ruled by philosopher-guardians, a clear articulation of an aristocratic ideal where the wisest and most virtuous govern. The distinction here is not merely numerical, but qualitative: the qualities of the rulers are paramount.

A Comparative Lens: Monarchy vs. Aristocracy

The nuances between these two forms of government become clearer when juxtaposed. While both involve a limited number of rulers (one or a few), their foundational principles diverge significantly.

| Feature | Monarchy | Aristocracy |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Rulers | One (single individual) | Few (a select group) |

| Basis of Authority | Individual's position, often hereditary or divine right | Perceived merit, virtue, wisdom, or excellence |

| Succession | Typically hereditary, sometimes elective | Selection based on qualification, not inherently hereditary |

| Ideal Form | Virtuous King ruling for the common good | Wise Council of the "best" ruling for the common good |

| Corrupted Form | Tyranny (rule for self-interest) | Oligarchy (rule by the wealthy/few for self-interest) |

| Primary Focus | The will and wisdom of the singular ruler | The collective wisdom and virtue of the elite group |

| Key Risk | Abuse of absolute power by one | Rule by a self-serving, unmeritorious elite |

Beyond the Definitions: The Nuance of Ancient Thought

The philosophers of the Great Books of the Western World understood that these categories were not always neat in practice. Aristotle, in particular, recognized that the purpose of the rule was as critical as the number of rulers. A king who rules justly for the common good is a monarch in the virtuous sense, but one who rules for personal gain becomes a tyrant. Similarly, an aristocracy where the truly "best" govern for all is admirable, but when the "best" devolve into a self-serving wealthy elite, it transforms into an oligarchy.

Indeed, the very health of a government hinged on whether its rulers, be they one or many, prioritized the welfare of the entire polis over their private interests. This ethical dimension is what elevates the classical definition of these government forms beyond mere structural descriptions.

Conclusion

The distinction between aristocracy and monarchy is more than an academic exercise; it is a profound philosophical tool for understanding the nature of power, justice, and good government. While both involve a concentration of authority in a limited number of hands, monarchy fundamentally rests on the individual authority of one, often through birthright, whereas aristocracy ideally rests on the collective merit and virtue of a chosen few.

These distinctions, meticulously explored by the foundational thinkers whose works comprise the Great Books, continue to resonate, urging us to question not just who governs, but how and why. In our ongoing quest for political wisdom, understanding these classical categories remains an indispensable first step.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Forms of Government Explained""

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Aristotle on Monarchy, Aristocracy, and Constitutional Government""