The Enduring Chasm: Discerning Opinion from Truth

In an age brimming with information, discerning the fundamental difference between a mere opinion and an established truth is more critical than ever. While often conflated in casual discourse, these two concepts occupy distinct realms in our pursuit of understanding and knowledge. An opinion is a subjective belief or judgment, often influenced by personal feelings, experiences, or interpretations, and may or may not be factually correct. Truth, conversely, refers to a statement or idea that corresponds to reality, is verifiable, and holds an objective validity independent of individual perception. This article explores this vital distinction, drawing on classical philosophical insights to illuminate why separating the two is paramount for genuine intellectual inquiry and the attainment of knowledge.

The Subjective Landscape of Opinion

An opinion is, at its core, a personal stance. It's what we think or feel about something. We form opinions constantly, about everything from the best coffee to complex political issues. They are often rooted in our individual perspectives, cultural backgrounds, and emotional responses.

Consider these characteristics of opinion:

- Subjective: Opinions are tied to the individual; what one person opines, another may dispute.

- Fallible: Opinions can be wrong. They are not necessarily supported by evidence or reason, or the evidence might be incomplete or misinterpreted.

- Variable: Opinions can change over time as new information or experiences come to light.

- Lacks Universal Agreement: While many might share an opinion, its validity doesn't depend on universal consensus.

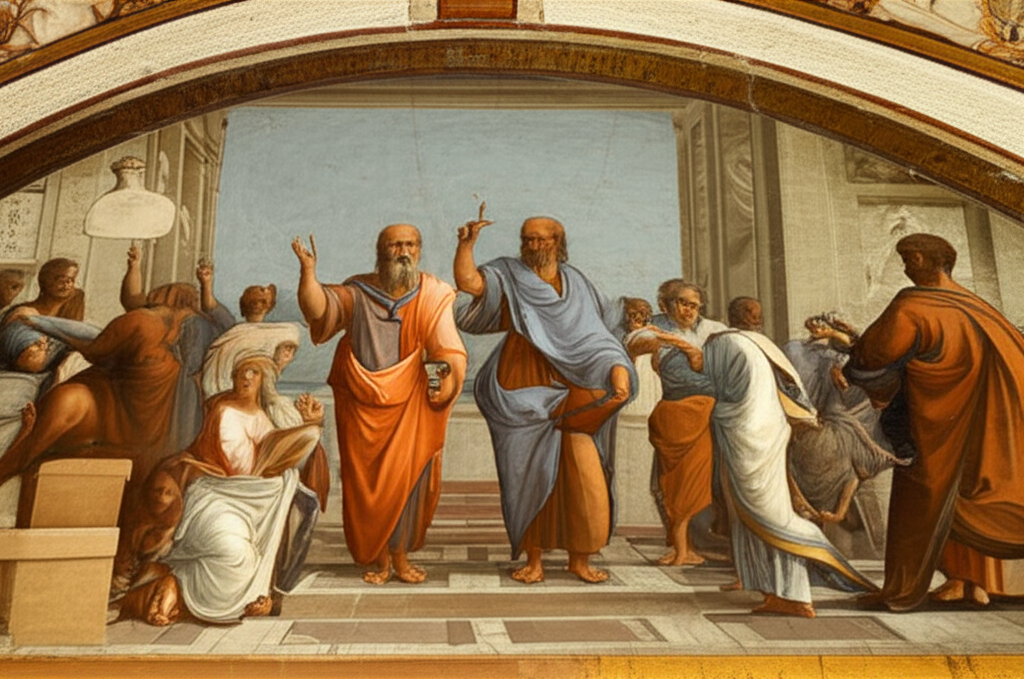

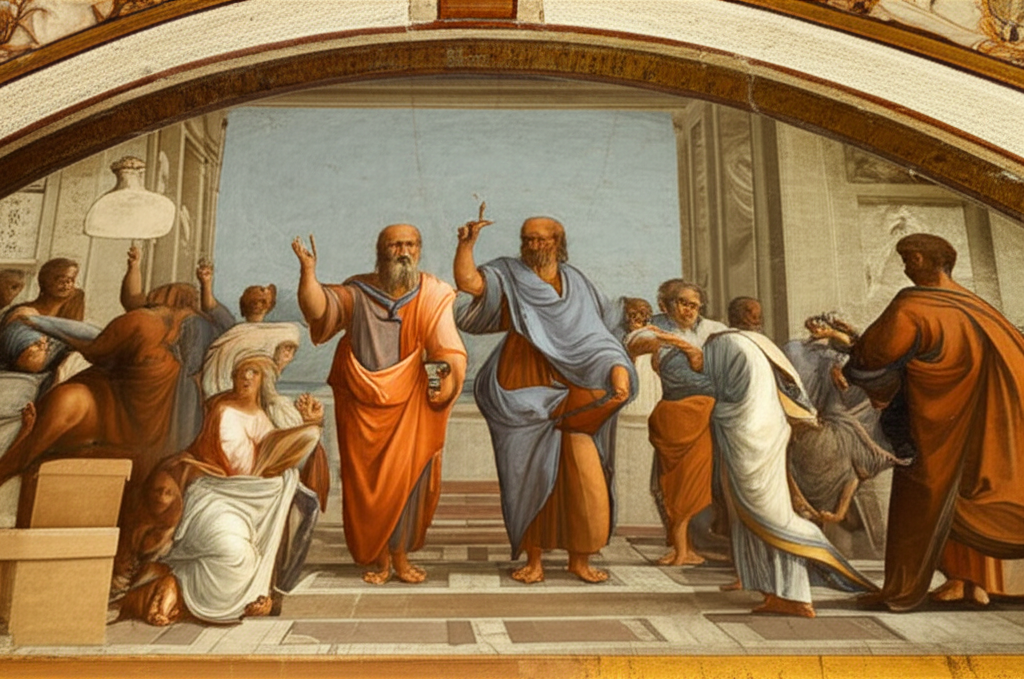

From the perspective of the Great Books of the Western World, figures like Plato often viewed opinion (doxa) as residing in the lower realms of the Divided Line – a world of shadows and appearances, far removed from true Being. It's the realm of what seems to be, rather than what is.

The Objective Anchor of Truth

Truth, in contrast, seeks to transcend individual perspective and establish a correspondence with reality itself. It's about what is, regardless of what we wish, feel, or believe. The pursuit of truth has been a central project of philosophy since its inception.

Key attributes of truth include:

- Objective: Truth exists independently of our beliefs or desires. The Earth is round, whether one believes it or not.

- Verifiable: Truth can, in principle, be demonstrated or proven through evidence, reason, and logical consistency.

- Consistent: Truth does not contradict itself.

- Universal (within its domain): A truth, once established, holds universally under its specific conditions.

Aristotle, in his metaphysical explorations, grappled with the nature of being and truth, often linking truth to the correct assertion or denial of what exists. For him, a statement is true if it says of what is that it is, and of what is not that it is not.

Bridging the Gap: Knowledge and the Dialectic

How do we move from the shifting sands of opinion to the firm ground of truth? This is where knowledge and the philosophical method of Dialectic become indispensable.

-

Knowledge as Justified True Belief: Philosophers often define knowledge as "justified true belief." This means for something to be considered knowledge, it must not only be believed by someone and be true, but also have adequate justification or evidence supporting it. An opinion becomes knowledge when it is proven to be true and the reasons for its truth are understood and defensible.

-

The Power of Dialectic: The Socratic method, a form of Dialectic, is a powerful tool for this transition. As explored in Plato's dialogues, Dialectic involves a rigorous exchange of ideas, questions, and answers, intended to expose weaknesses in arguments and lead participants to a deeper understanding of the subject matter. It's a process of critical inquiry that systematically tests assumptions and pushes beyond superficial opinions to uncover underlying truths.

| Feature | Opinion | Truth |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | Subjective, personal judgment | Objective, corresponds to reality |

| Basis | Belief, feeling, interpretation, experience | Evidence, reason, verifiable facts |

| Validity | Can be right or wrong, often unproven | Demonstrably correct, universally applicable |

| Goal | Expressing a viewpoint | Accurately describing reality |

| Mutability | Easily changes | Enduring, consistent |

| Relation to Knowledge | A starting point, but not knowledge itself | A necessary component of knowledge |

Why the Distinction Matters

The ability to differentiate between opinion and truth is not merely an academic exercise; it has profound implications for our daily lives, societal discourse, and the advancement of civilization.

- Informed Decision-Making: Whether choosing a medical treatment or voting in an election, basing decisions on verifiable truths rather than unsubstantiated opinions leads to better outcomes.

- Critical Thinking: Recognizing the difference fosters critical thinking skills, allowing us to evaluate claims, question assumptions, and seek evidence.

- Productive Discourse: When discussing contentious issues, knowing whether we are presenting an opinion or a truth helps us engage more constructively. It allows for respectful disagreement on opinions while demanding evidence for factual claims.

- Combating Misinformation: In an era of rampant misinformation, the ability to identify and challenge opinions masquerading as truth is vital for maintaining a well-informed populace.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Allegory of the Cave explained" or "Socratic Method explained""

Conclusion: The Lifelong Pursuit

The distinction between opinion and truth is a cornerstone of philosophical inquiry and a fundamental requirement for anyone seeking genuine knowledge. While opinions are a natural and often valuable part of human experience, they must not be mistaken for the objective reality that truth represents. Through critical engagement, the disciplined application of reason, and the rigorous process of Dialectic, we can strive to move beyond mere belief towards a more profound and justified understanding of the world. This journey, illuminated by the wisdom of the Great Books of the Western World, is a lifelong pursuit, essential for both individual enlightenment and the collective good.