The Enduring Definition of Rhetoric: A Philosophical Inquiry

Rhetoric is, at its core, the art of persuasion. It is not merely flowery speech or manipulative trickery, but rather a profound human endeavor deeply intertwined with language, thought, and the shaping of public opinion. From the ancient agora to the modern digital forum, understanding its definition is crucial for navigating the complex landscape of human communication and influence. This article delves into the philosophical underpinnings of rhetoric, drawing insights from the venerable texts of the Great Books of the Western World, to illuminate its multifaceted nature.

The Elusive Definition: What is Rhetoric?

At its most fundamental, rhetoric is the study and practice of effective communication and persuasion. It is the means by which ideas are conveyed, arguments are constructed, and beliefs are influenced. While often associated with public speaking, its scope extends to all forms of communication—written, visual, and even non-verbal. The constant thread, however, is the deliberate intent to achieve a particular effect on an audience.

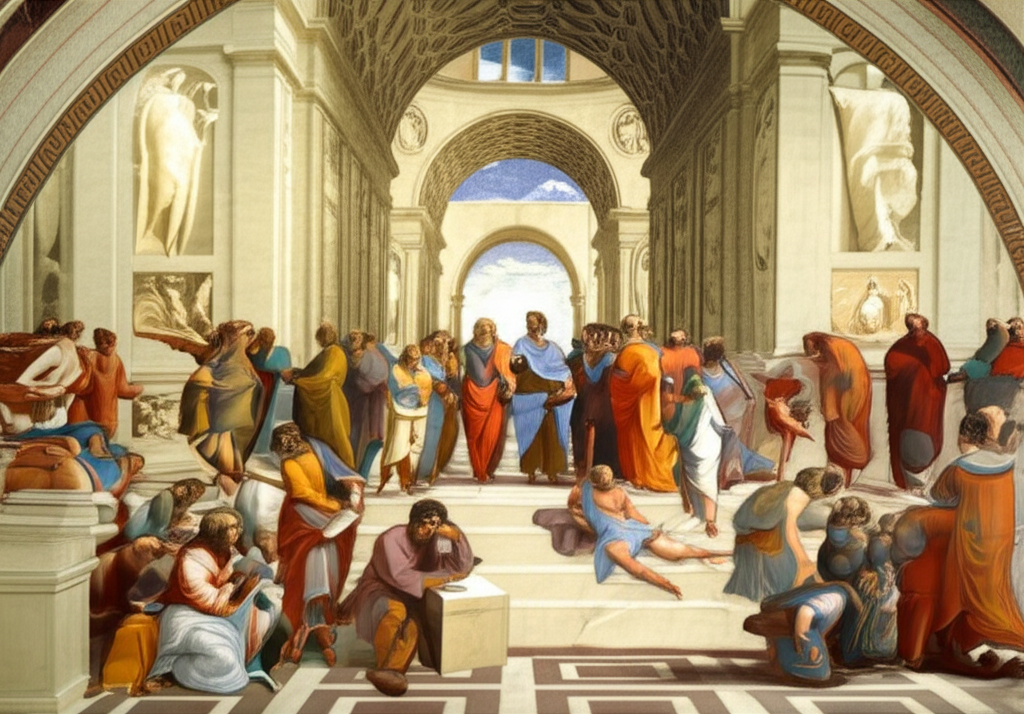

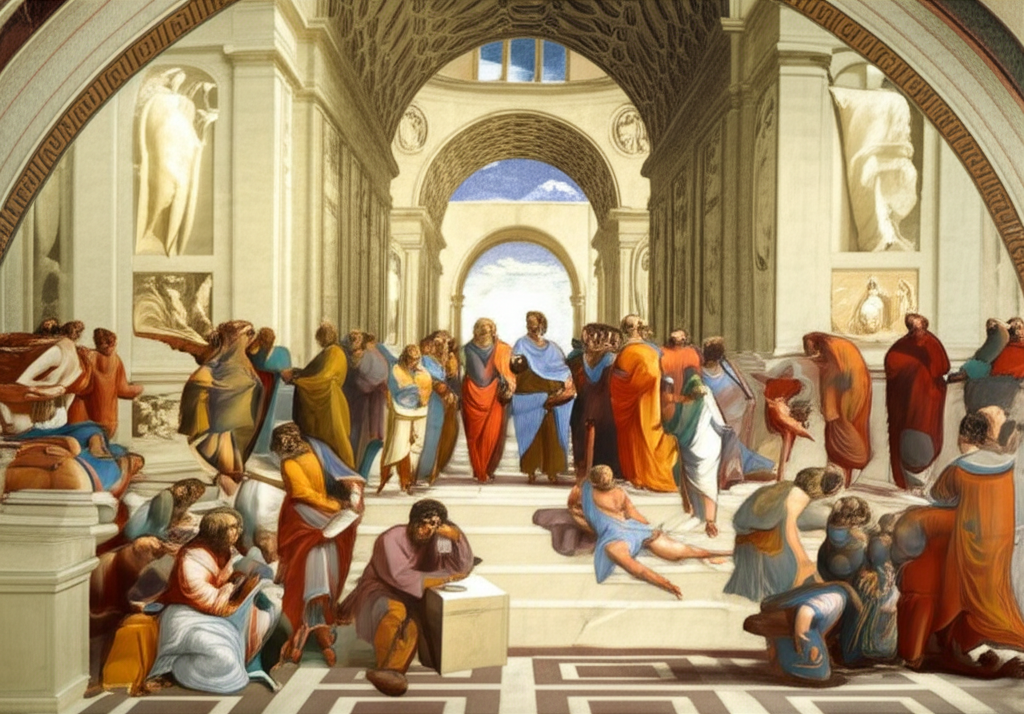

Ancient Perspectives: Pillars from the Great Books

The foundational understanding of rhetoric is deeply rooted in classical antiquity, with philosophers and orators grappling with its power and purpose.

Plato's Skepticism

In works like Gorgias, Plato presents a rather critical view of rhetoric. He often portrays it as a dangerous art, a form of flattery or mere sophistry, capable of swaying an ignorant populace without regard for truth or justice. For Plato, true knowledge (episteme) was superior to mere belief (doxa), and rhetoric, in his more cynical moments, seemed to traffic solely in the latter, appealing to emotions rather than reason. He saw it as a means to create opinion rather than reveal truth.

Aristotle's Pragmatism: The Art of Persuasion

Aristotle, in his seminal work Rhetoric, offers a more systematic and nuanced definition. He famously defines rhetoric as "the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion." This is a pragmatic and descriptive approach, viewing rhetoric not as inherently good or evil, but as a neutral tool, an art (techne) that can be used for various ends. He meticulously categorizes the three primary modes of persuasion:

- Ethos: Appealing to the speaker's credibility or character.

- Pathos: Appealing to the audience's emotions.

- Logos: Appealing to logic and reason.

Aristotle's framework remains incredibly influential, providing a comprehensive understanding of how language is employed to influence opinion.

Roman Eloquence: Cicero and Quintilian

Later Roman thinkers, such as Cicero and Quintilian, built upon the Greek foundations, emphasizing the ideal orator as a virtuous citizen skilled in both wisdom and eloquence.

- Cicero, a prolific orator and philosopher, stressed the importance of rhetoric in public life and governance. For him, the orator must be well-versed in philosophy, law, and history to wield language effectively and justly.

- Quintilian, in Institutio Oratoria, detailed the education of the perfect orator, defining rhetoric as the "art of speaking well." He believed that a true orator must be "a good man skilled in speaking," thereby linking ethical character directly to rhetorical prowess.

The Interplay of Language and Opinion

At the heart of any definition of rhetoric lies the inseparable relationship between language and opinion.

Language as the Vehicle

Language is the indispensable medium through which rhetoric operates. It is not merely a tool for conveying information but a dynamic force that shapes perception, constructs reality, and evokes emotional responses. The careful selection of words, the structure of sentences, the use of metaphor, and the rhythm of speech all contribute to the rhetorical effect. Without the sophisticated deployment of language, persuasion would be impossible.

Shaping and Reflecting Opinion

One of the primary aims of rhetoric is to influence opinion. Whether in a courtroom, a political debate, or a philosophical discourse, the rhetor seeks to align the audience's beliefs with their own. However, rhetoric also reflects existing opinion. Effective persuaders are keenly aware of their audience's predispositions, values, and prevailing sentiments, tailoring their arguments to resonate with these established views. It's a two-way street: rhetoric both molds and is molded by the collective psyche.

Why Does the Definition Matter Today?

In an age saturated with information and diverse viewpoints, understanding the definition of rhetoric is more critical than ever. It empowers us to:

- Critically analyze: Discern persuasive strategies in media, politics, and everyday interactions.

- Communicate effectively: Articulate our own thoughts and arguments with clarity and impact.

- Engage thoughtfully: Participate in public discourse with a nuanced appreciation for how language shapes opinion.

By returning to the classical texts that first explored this profound art, we gain not just a historical understanding, but a practical toolkit for navigating the complexities of human influence.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Aristotle Rhetoric summary" "Plato's Critique of Rhetoric""