The Definition of Quality and Form: A Metaphysical Inquiry

The quest to understand reality often leads us to fundamental questions about what constitutes an object, an idea, or even an experience. Among the most enduring of these inquiries are the concepts of Quality and Form. Far from mere academic distinctions, these terms represent cornerstones of metaphysical thought, shaping our understanding of being, identity, and the very structure of the world we inhabit. This article delves into their definitions, tracing their evolution through the annals of Western philosophy, particularly as explored in the Great Books of the Western World, to illuminate their profound significance.

Unpacking the Fundamentals: A Summary

At its core, Form refers to the essential structure, blueprint, or organizing principle that gives something its specific nature or identity. It's what makes a thing what it is, irrespective of its material composition. Quality, on the other hand, describes the attributes, characteristics, or properties that belong to a thing, allowing us to perceive and distinguish it. Together, these concepts form the bedrock of metaphysics, inviting us to ponder how objects exist, what defines them, and how we come to know their inherent nature.

The Elusive Nature of Definition in Philosophy

Defining terms like Quality and Form is no trivial matter. Unlike empirical sciences that often define through observation and measurement, philosophy grapples with concepts that are often abstract, universal, and foundational. To define them is to engage in a deep metaphysical exploration, questioning the very fabric of existence and our capacity to apprehend it. Philosophers from Plato to Kant have wrestled with these definitions, revealing how our understanding of reality itself hinges on their precise articulation.

Form: The Blueprint of Being and Essence

The concept of Form has perhaps the richest and most influential lineage in Western thought. It speaks to the underlying structure or essence that makes something intelligible.

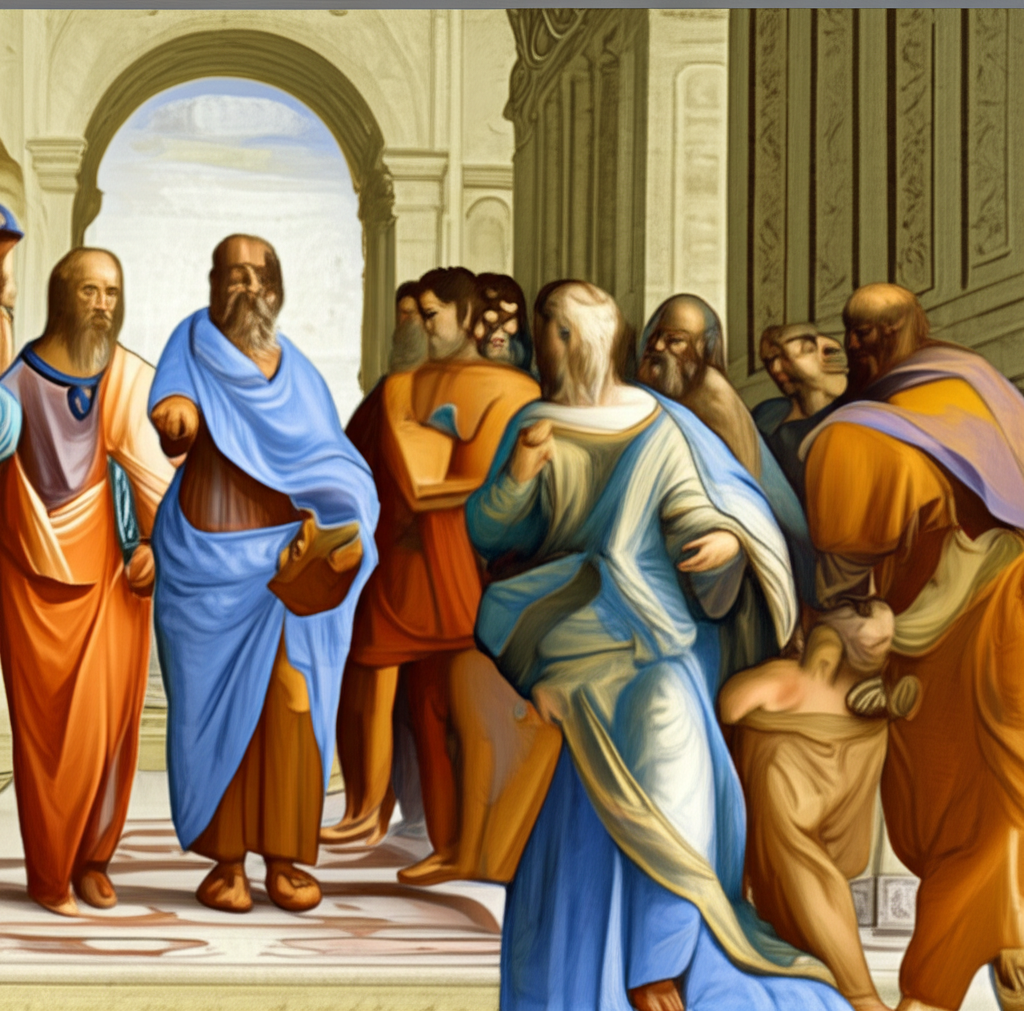

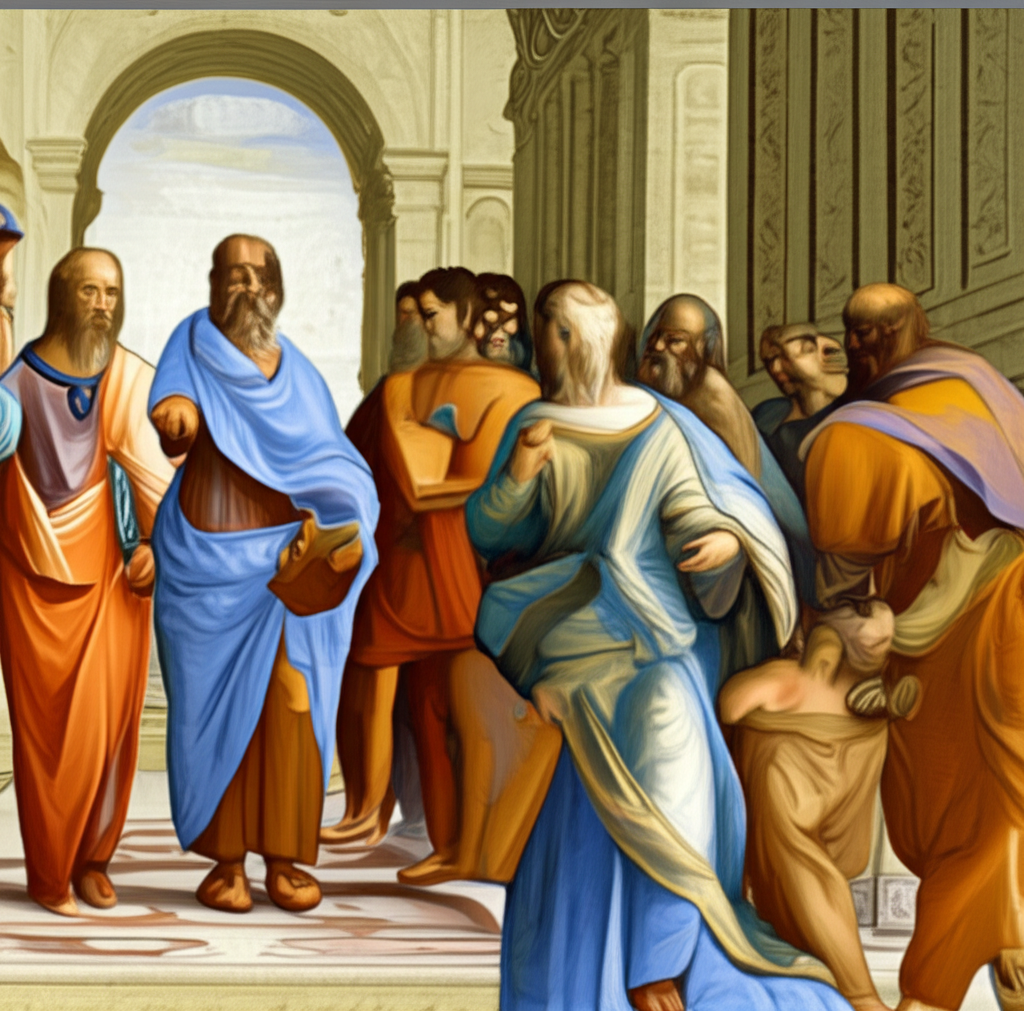

Plato's Ideal Forms: The Realm of Pure Being

For Plato, as articulated in dialogues like Phaedo and Republic, Form (or Idea, Eidos) exists independently of the material world. These are eternal, unchanging, perfect archetypes – the true reality – of which physical objects are mere imperfect copies. The Form of Beauty, for instance, is not a beautiful object, but the perfect, intelligible essence of Beauty itself, accessible only through reason. This metaphysical realm of Forms provides the ultimate definition for all that exists.

Aristotle's Immanent Forms: Structure Within Matter

Aristotle, Plato's most famous student, offered a significant departure. In works like Metaphysics and Physics, he argued that Form is not separate from matter but is inherent within it. For Aristotle, Form is the actualizing principle that gives shape and purpose to matter, making a thing what it is. A statue's Form is its shape, which actualizes the potential of the bronze matter. This concept, known as hylomorphism, sees Form and matter as inseparable components of any substance. The Form of a human being is its soul, which organizes and animates the body.

A Comparative Glimpse at Form

| Aspect | Platonic Form | Aristotelian Form |

|---|---|---|

| Existence | Transcendent; exists independently of the material world | Immanent; exists within and inseparable from matter |

| Nature | Perfect, eternal, unchanging archetype | Actualizing principle, essence, structure |

| Relation to Matter | Model for imperfect copies | Organizes and gives purpose to matter |

| Knowledge | Attained through intellect and reason alone | Attained through empirical observation and reason |

Quality: The Attributes and Characteristics of Existence

If Form defines what a thing is, Quality describes how it is. It refers to the attributes, characteristics, or properties that distinguish one thing from another.

Aristotle's Categories: Quality as a Mode of Being

Aristotle, in his Categories, identifies Quality as one of the ten fundamental ways something can be predicated or described. It refers to the inherent nature of a thing that allows it to be called "white," "hot," "virtuous," or "large." These qualities are not the substance itself, but rather its modifications or affections. They are intrinsic to the object and contribute to its particularity.

Locke's Primary and Secondary Qualities: Objective vs. Subjective

Centuries later, John Locke, in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding, introduced a crucial distinction between Primary Qualities and Secondary Qualities. This distinction became central to the empiricist tradition and our understanding of perception.

-

Primary Qualities: These are inherent properties of an object that exist independently of an observer. They are objective, measurable, and inseparable from the object itself, such as:

- Solidity

- Extension (size)

- Figure (shape)

- Motion or Rest

- Number

- Example: A billiard ball's roundness and size remain the same whether you perceive them or not.

-

Secondary Qualities: These are powers in objects to produce sensations in us. They are subjective, mind-dependent, and arise from the interaction between the object's primary qualities and our sensory organs. They include:

- Color (e.g., redness)

- Sound (e.g., loudness)

- Taste (e.g., sweetness)

- Smell (e.g., fragrance)

- Temperature (e.g., heat)

- Example: The "redness" of a rose is not inherent in the rose itself but is a sensation produced in our minds by the rose's primary qualities interacting with light and our eyes.

This distinction profoundly impacted subsequent philosophical thought, particularly in epistemology and the philosophy of mind, questioning the reliability of our sensory experience in grasping objective reality.

The Interplay: Quality, Form, and Metaphysics

The relationship between Quality and Form is intricate and deeply metaphysical. Form often dictates the potential qualities a thing can possess. The Form of a human being, for instance, implies the capacity for reason, morality, and certain physical attributes (qualities). Conversely, the specific qualities we observe in a thing allow us to infer its underlying form or nature.

Consider a piece of marble. Its Form (in the Aristotelian sense) as "marble" gives it certain inherent qualities: hardness, coolness to the touch, specific crystalline structure. If a sculptor then imposes the Form of "statue" upon it, new qualities emerge: beauty, grace, perhaps a narrative quality.

The ongoing philosophical debate explores:

- Can a thing exist without any qualities? (A formless void?)

- Can qualities exist without a substrate or form to which they adhere? (Hume's bundle theory suggested qualities are all we ever perceive, not an underlying substance).

- How do changes in qualities affect the identity of a form? (If a person's qualities change drastically, is it still the same person?)

These questions underscore the enduring relevance of Quality and Form in our continuous attempt to define and comprehend the very nature of existence.

Conclusion: Enduring Pillars of Philosophical Inquiry

The concepts of Quality and Form are more than just philosophical terms; they are essential lenses through which we examine the fundamental structure of reality. From Plato's transcendent Forms to Aristotle's immanent essences, and from Locke's objective primary qualities to his subjective secondary ones, philosophers have continually refined our understanding of what constitutes being. These concepts remain vital tools in metaphysics, guiding our inquiries into identity, change, perception, and the very possibility of knowledge. To engage with Quality and Form is to engage with the core questions that have captivated thinkers for millennia, shaping our understanding of ourselves and the cosmos.

YouTube: Plato's Theory of Forms Explained

YouTube: Locke Primary and Secondary Qualities Philosophy

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "The Definition of Quality and Form philosophy"