The Indissoluble Knot: Examining the Connection Between Wealth and Justice

The relation between wealth and justice has been a cornerstone of philosophical inquiry since antiquity, a persistent challenge to human societies and the very concept of the State. This article delves into how thinkers across the Great Books of the Western World have grappled with this complex interplay, exploring whether wealth is an impediment or an enabler of justice, and the role of governance in mediating this profound connection. From ancient Greek city-states to the Enlightenment's social contracts, the question of who deserves what, and how resources should be distributed, remains central to our understanding of a just society.

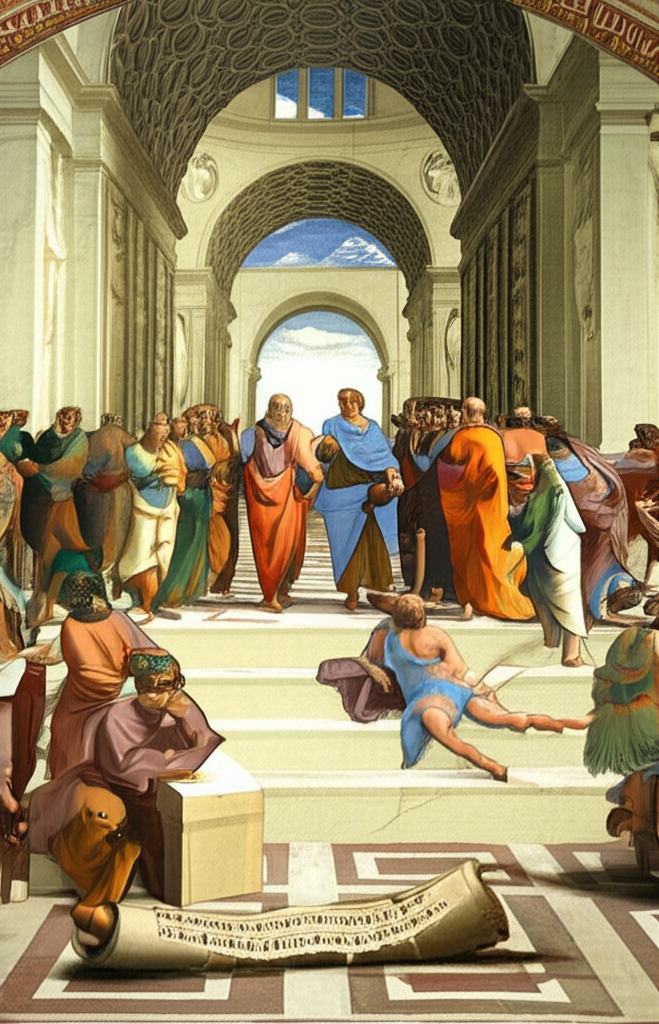

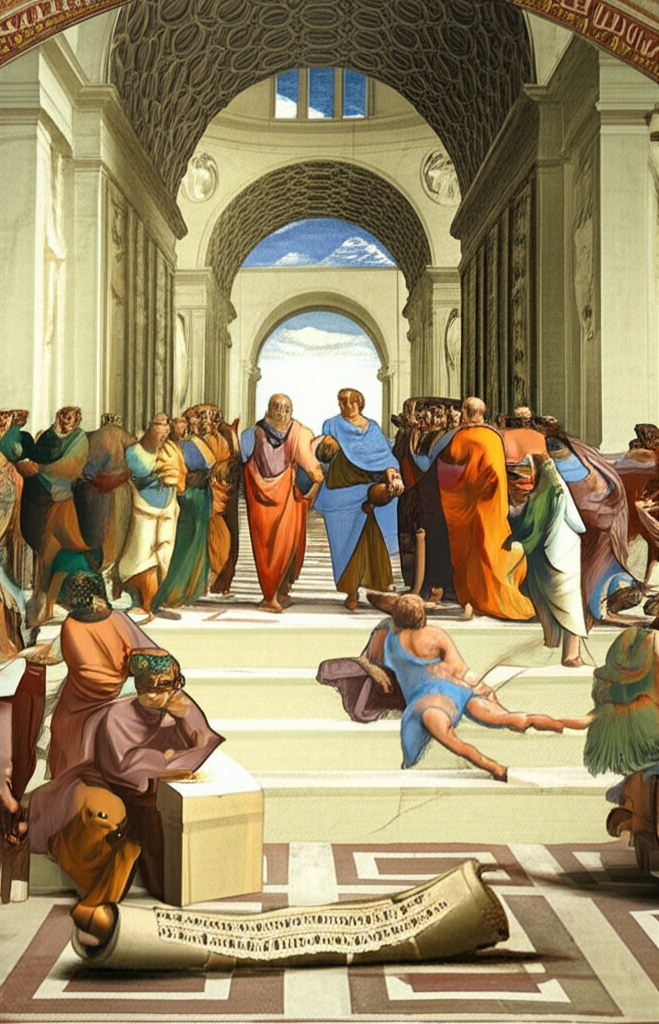

Ancient Roots: Plato, Aristotle, and the Foundations of Justice

Our journey into the relation between wealth and justice must invariably begin with the ancient Greeks, whose foundational texts laid the groundwork for much of Western political thought.

Plato's Ideal State and the Abolition of Private Property

In Plato's Republic, the pursuit of justice is paramount, envisioned as a harmonious balance within the soul and, by extension, within the State. Plato, through Socrates, famously posits that for the guardian class – those responsible for ruling and defending the city – private wealth should be abolished. This radical proposal stems from the belief that private property and the pursuit of riches corrupt the soul, fostering self-interest over the common good.

- Key Idea: Justice in the State is achieved when each class performs its function without interference, and for the rulers, freedom from the distractions of wealth is crucial for impartial governance.

- Plato's Concern: The accumulation of wealth by the ruling class leads to factionalism, greed, and ultimately, the decay of the ideal State into timocracy, oligarchy, democracy, and finally, tyranny.

Aristotle's Practical Justice and Distributive Principles

Aristotle, a student of Plato, offered a more pragmatic view, acknowledging the inevitability and even the utility of private property. In his Nicomachean Ethics and Politics, Aristotle distinguishes between different forms of justice:

- Distributive Justice: Concerned with the fair allocation of wealth, honors, and other goods based on merit. Aristotle recognized that different political systems would define "merit" differently (e.g., virtue in an aristocracy, birth in an oligarchy, citizenship in a democracy). The State's role here is to ensure that distributions align with its chosen principle of merit.

- Corrective Justice: Aims to rectify imbalances that arise from voluntary transactions (like contracts) or involuntary ones (like theft or assault), restoring equality. This form of justice is blind to the social standing or wealth of the parties involved.

Aristotle believed that extreme disparities in wealth could destabilize the State, leading to envy among the poor and arrogance among the rich. He advocated for a strong middle class as the foundation of a stable and just polity, where citizens could participate actively without being consumed by either destitution or excessive luxury.

The Medieval Interlude: Divine Law, Property, and Charity

The medieval period, heavily influenced by Christian theology, re-evaluated the relation between wealth and justice through the lens of divine and natural law. Thinkers like Thomas Aquinas, drawing on Aristotle and Christian doctrine, affirmed the right to private property but with significant caveats.

- Private Property for the Common Good: Aquinas argued that private property is permissible and even beneficial for peace and order, as individuals tend to care more for what is their own. However, this right is not absolute. The ultimate purpose of wealth is the common good, and individuals are obligated to use their surplus wealth to aid the needy.

- Theological Justice: For Aquinas, true justice transcended mere legal definitions, encompassing charity and the moral obligation to alleviate suffering. The State, guided by natural law, had a role in upholding a just social order that reflected divine principles, which included ensuring basic needs were met.

The Enlightenment: Property Rights, Liberty, and the Social Contract

The Enlightenment ushered in a new era of thinking, emphasizing individual rights, liberty, and the social contract. The relation between wealth, justice, and the State was re-examined through the lens of nascent capitalism and evolving political structures.

John Locke and the Labor Theory of Property

John Locke, in his Two Treatises of Government, presented a powerful argument for natural rights, including the right to private property. His famous labor theory of value posits that when an individual mixes their labor with unowned resources, they make those resources their own.

- Key Principle: Property is a natural right, predating the State, and the primary purpose of government is to protect these rights, including property.

- Limitations: Locke initially posited limitations on property acquisition (enough and as good left for others, spoilage), but the introduction of money complicated these, allowing for greater accumulation without spoilage.

- Justice as Protection: For Locke, justice is largely about protecting individual liberties and property from infringement by others or by an overreaching State.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the Origins of Inequality

In stark contrast to Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, particularly in his Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men, viewed the institution of private property as the very source of social inequality and injustice.

- The Fall from Nature: Rousseau argued that in the state of nature, humans were essentially equal. The moment someone enclosed a piece of land and declared, "This is mine," and others were foolish enough to believe him, was the moment civil society, with its attendant inequalities and injustices, truly began.

- The Corrupting Influence: For Rousseau, the accumulation of wealth and property leads to competition, vanity, and the creation of laws designed to protect the rich, thereby perpetuating injustice. The State, in this view, often becomes an instrument for maintaining existing inequalities rather than correcting them.

- Social Contract for Equality: Rousseau's Social Contract sought to create a political order where the general will would guide laws, aiming to restore a measure of equality and true liberty, suggesting a more active role for the State in shaping economic outcomes for the sake of justice.

Modern Dilemmas: Wealth, Inequality, and the State's Ongoing Role

The dialogue initiated by these historical figures continues to shape contemporary discussions about the relation between wealth and justice. Modern philosophy grapples with questions of economic inequality, global justice, and the appropriate extent of State intervention.

- Utilitarianism and Welfare: Thinkers like Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill proposed that justice is achieved by maximizing overall happiness or utility. This perspective can justify wealth redistribution if it leads to greater aggregate well-being, even if it means infringing on absolute property rights.

- Rawls's Theory of Justice: John Rawls, in A Theory of Justice, introduced the "difference principle," stating that social and economic inequalities are permissible only if they benefit the least advantaged members of society. This places a strong emphasis on the State's role in creating a just basic structure that mitigates the effects of unequal wealth distribution.

- Nozick's Entitlement Theory: Robert Nozick, in Anarchy, State, and Utopia, offers a powerful counterpoint, arguing that justice in holdings is entirely about how wealth is acquired and transferred, not its final distribution. Any State intervention beyond protecting property and enforcing contracts is seen as unjust, infringing on individual liberty.

These diverse perspectives highlight the enduring complexity. Is justice about equality of outcome, equality of opportunity, or simply the protection of justly acquired property? The State's role shifts dramatically depending on which philosophical framework is adopted: from a minimalist protector of property to an active agent of redistribution and social welfare.

Conclusion: The Unending Quest for a Just Distribution

The relation between wealth and justice is not a static concept but a dynamic philosophical challenge that has evolved with human society. From Plato's ideal State devoid of private property for its guardians, to Aristotle's balanced middle ground, Locke's emphasis on natural rights, and Rousseau's critique of property as the root of inequality, the Great Books offer a rich tapestry of thought.

Ultimately, the quest for justice in the face of wealth disparities remains one of humanity's most pressing concerns. The role of the State in mediating this relation is constantly debated, reflecting our ongoing struggle to define what it truly means to live in a fair and equitable society. The historical dialogue reminds us that understanding this connection is not merely an academic exercise, but a fundamental prerequisite for building a flourishing human community.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Plato Republic Justice Wealth"

-

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Aristotle Nicomachean Ethics Distributive Justice"