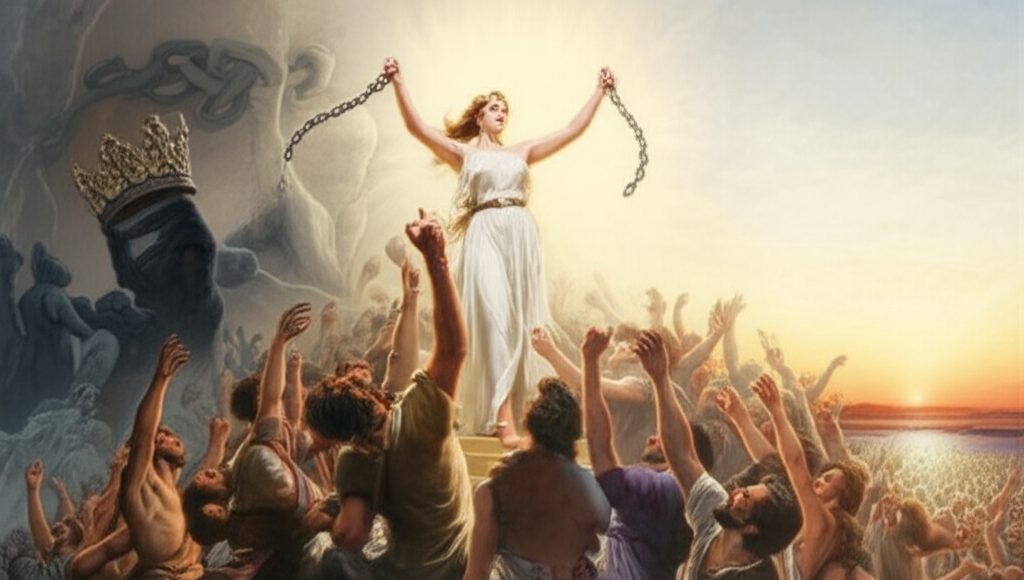

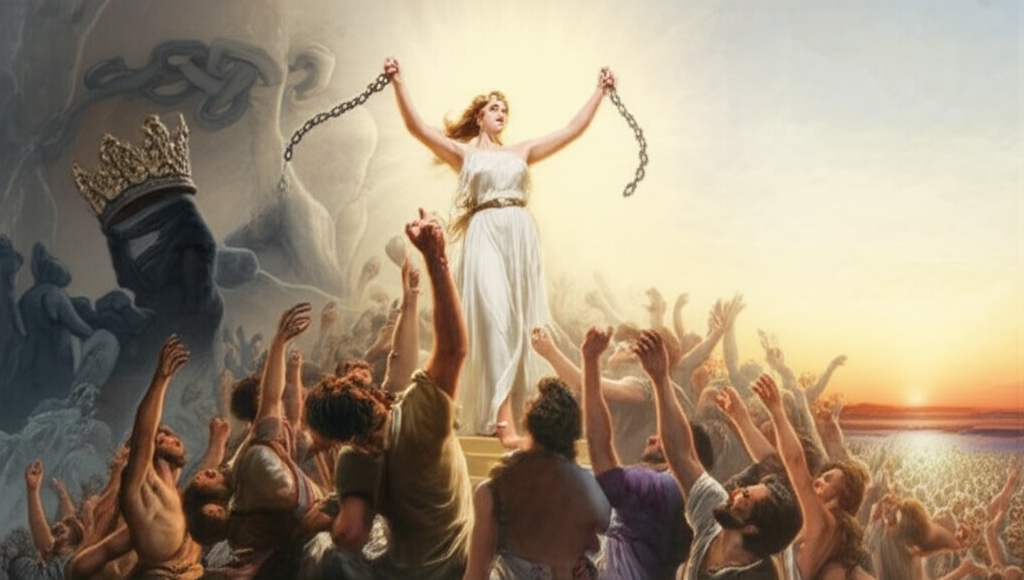

The Inevitable Pendulum: Exploring the Connection Between Tyranny and Revolution

Summary: The intimate connection between tyranny and revolution is one of the most enduring themes in political philosophy. Tyrannical government, characterized by the abuse of power and suppression of individual liberties, often sows the seeds of its own destruction, leading inevitably to popular uprisings and the demand for radical change. This article delves into the philosophical underpinnings of this dynamic, drawing upon the wisdom of the Great Books of the Western World to illuminate the cyclical nature of power, oppression, and rebellion.

I. The Genesis of Discontent: Understanding Tyranny

From the earliest philosophical inquiries, thinkers have grappled with the nature of unjust rule. Tyranny is not merely strong leadership; it is the perversion of legitimate government, where power is exercised for the self-interest of the ruler or a small elite, rather than for the common good.

A. The Philosophical Foundations of Tyranny

Ancient Greek philosophers were among the first to meticulously categorize forms of government and identify the pathologies that lead to tyranny.

- Plato's Republic: Plato famously describes the devolution of ideal states into progressively worse forms, culminating in tyranny. He argues that an oligarchy, driven by insatiable wealth accumulation, breeds a democracy, which in turn, due to its excessive freedom and lack of discipline, opens the door for a demagogue to seize absolute power. The tyrant, initially appearing as a protector, soon becomes a master, enslaving the very people he promised to liberate.

- Aristotle's Politics: Aristotle, in his empirical study of over 150 constitutions, defines tyranny as a deviation from monarchy, where the ruler governs for personal benefit, not the public good. He meticulously details the methods tyrants use to maintain power – sowing distrust, impoverishing the populace, and waging war – all designed to prevent the people from uniting against them. Aristotle also sagely notes that revolutions against tyrannies are often driven by a quest for equality or a reaction to the insolence of the ruler.

B. Characteristics of a Tyrannical Government

A tyrannical government exhibits specific traits that systematically erode the social contract and foster resentment:

- Suppression of Dissent: Free speech, assembly, and opposition are ruthlessly crushed.

- Arbitrary Rule: Laws are applied inconsistently or ignored entirely by the ruler.

- Economic Exploitation: Resources are often diverted to benefit the ruling class, leaving the populace impoverished.

- Fear and Surveillance: The populace lives under constant threat and observation, fostering a climate of terror.

- Lack of Accountability: The ruler is above the law and cannot be challenged or removed through legitimate means.

II. The Inevitable Spark: The Rise of Revolution

When the bonds of legitimate government are severed by tyranny, the stage is set for revolution. This is not merely a spontaneous outburst but often the culmination of prolonged suffering and a philosophical re-evaluation of the ruler's legitimacy.

A. The Social Contract Betrayed

The Enlightenment thinkers profoundly articulated the philosophical grounds for revolution when tyranny takes hold.

- John Locke's Two Treatises of Government: Locke posits that government derives its legitimacy from the consent of the governed, based on a social contract to protect life, liberty, and property. When a ruler acts contrary to this trust, becoming a tyrant who violates these natural rights, the people retain the right—indeed, the duty—to resist and overthrow that government. For Locke, tyranny is the exercise of power beyond right, and against it, there is no appeal but to Heaven (i.e., force).

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau's The Social Contract: Rousseau argues that legitimate government must reflect the "general will" of the people. When a ruler usurps power and imposes their particular will over the general will, the social contract is broken. Though Rousseau was wary of violent revolution, his philosophy provides a powerful justification for popular sovereignty and the right of the people to reconstitute their government when it becomes tyrannical.

B. Catalysts for Revolutionary Action

While tyranny provides the underlying conditions, specific catalysts often ignite the flame of revolution:

- Gross Injustice: Pervasive legal inequality, corrupt courts, or targeted oppression of specific groups.

- Economic Hardship: Famine, crippling taxes, or widespread poverty exacerbated by the regime's mismanagement.

- Loss of Trust: When the government's actions are consistently perceived as deceitful, self-serving, or fundamentally hostile to the people.

- Intellectual Ferment: The spread of ideas that challenge the legitimacy of the tyrannical regime and offer alternative visions of government.

III. The Intertwined Dance: Connection and Consequences

The connection between tyranny and revolution is cyclical, often leading to a complex dance of power, resistance, and the potential for new forms of oppression.

A. Revolution as the Ultimate Response to Tyranny

Revolution is often the violent redress for the grievances accumulated under tyranny. It represents a societal reset, an attempt to dismantle the old, oppressive structures and build a new, more just government. However, the path from tyranny to a stable, free society is fraught with peril.

Table 1: Philosophical Perspectives on Tyranny and Revolution

| Philosopher | View on Tyranny | Justification for Revolution | Key Contribution to the Connection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plato | Degenerate form of state; rule by personal desire. | Not explicitly, but implicitly by the state's inherent instability. | Showed how excessive freedom/license can lead to tyranny. |

| Aristotle | Perversion of monarchy; rule for self-interest. | When rulers act unjustly or for private gain. | Detailed causes of revolutions against tyrannies. |

| Locke | Exercise of power beyond right; violation of natural rights. | An inherent right of the people when the government breaks the social contract. | Established the right to revolution as a check on tyrannical power. |

| Rousseau | Usurpation of popular sovereignty; subversion of general will. | When the particular will replaces the general will; implies right to reconstitute government. | Emphasized popular sovereignty as the ultimate authority against tyranny. |

| Machiavelli | A means to acquire and maintain power, often necessary. | Not a moral justification, but an observation of power dynamics and popular discontent. | Analyzed the practical causes of rebellion and how rulers avoid it. |

B. The Cycle of Power and Rebellion

- Niccolò Machiavelli's The Prince and Discourses: Machiavelli, ever the pragmatist, understood that rulers, whether tyrannical or not, must contend with the populace. He observed that tyranny often creates its own enemies, and while a prince might rule by fear, he must avoid being hated, lest he face revolution. He also recognized the cyclical nature of government, where one form can naturally decay into another, implying that revolutions are an inherent part of the political landscape.

- Thomas Hobbes' Leviathan: Hobbes, deeply scarred by the English Civil War, argued for an absolute sovereign to prevent the chaos of the "state of nature." While he saw tyranny as a lesser evil than anarchy, his work implicitly highlights the extreme pressures that can lead to revolution – specifically, the breakdown of order and the failure of government to provide security. The very fear he sought to alleviate through absolute power is often the fuel for rebellion when that power becomes oppressive.

The historical record is replete with examples of this connection: from the Roman Republic's overthrow of its kings to the American and French Revolutions, and countless others across the globe. Each instance underscores the precarious balance between the authority of government and the fundamental rights of its citizens. When that balance tips decisively towards tyranny, revolution often emerges as the painful, yet sometimes necessary, mechanism for recalibrating the scales of justice and freedom.

Conclusion: The Enduring Connection

The connection between tyranny and revolution is not merely a historical coincidence but a profound philosophical insight into the nature of political power. As the Great Books reveal, tyranny is an inherently unstable form of government, fostering the very conditions—injustice, oppression, and the betrayal of public trust—that inevitably lead to its violent overthrow. While revolution is a tumultuous and often destructive process, it frequently arises as the ultimate recourse against a regime that has forfeited its legitimacy. Understanding this enduring dynamic is crucial for any society seeking to build and maintain a just and stable government that truly serves its people.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Republic: The Decline of the State and Tyranny Explained""

2. ## 📹 Related Video: KANT ON: What is Enlightenment?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""John Locke and the Right to Revolution: Social Contract Theory""