The Unbreakable Nexus: Exploring the Connection Between Revolution and Justice

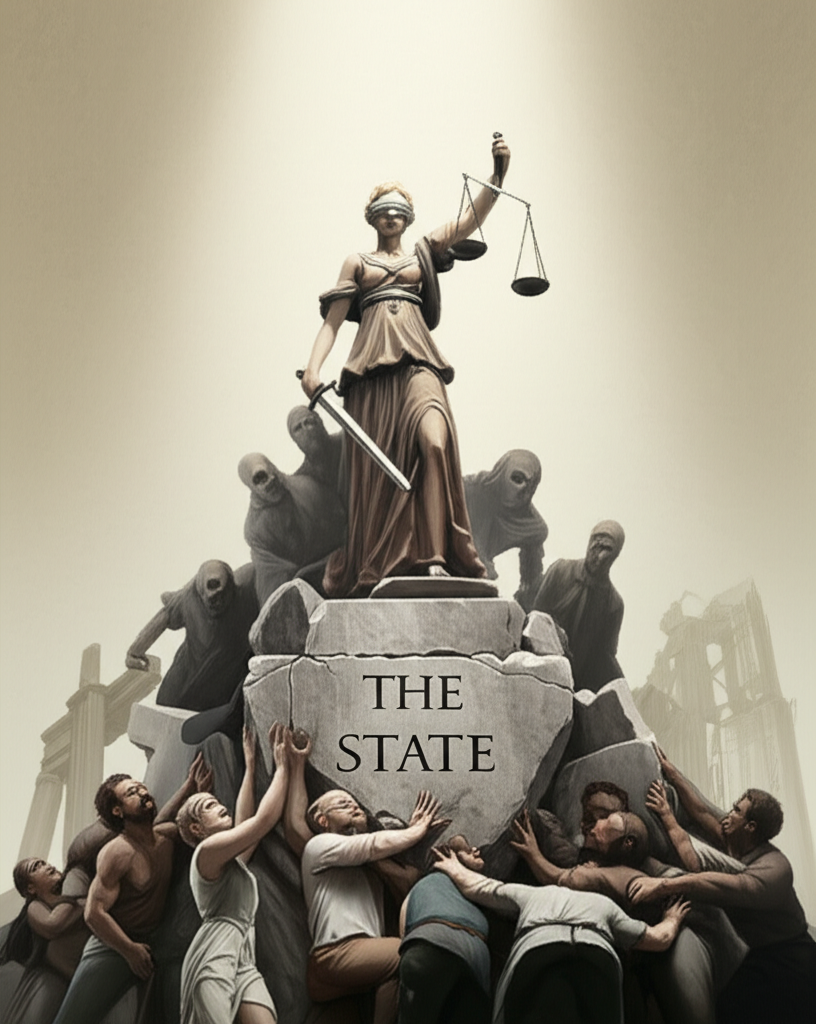

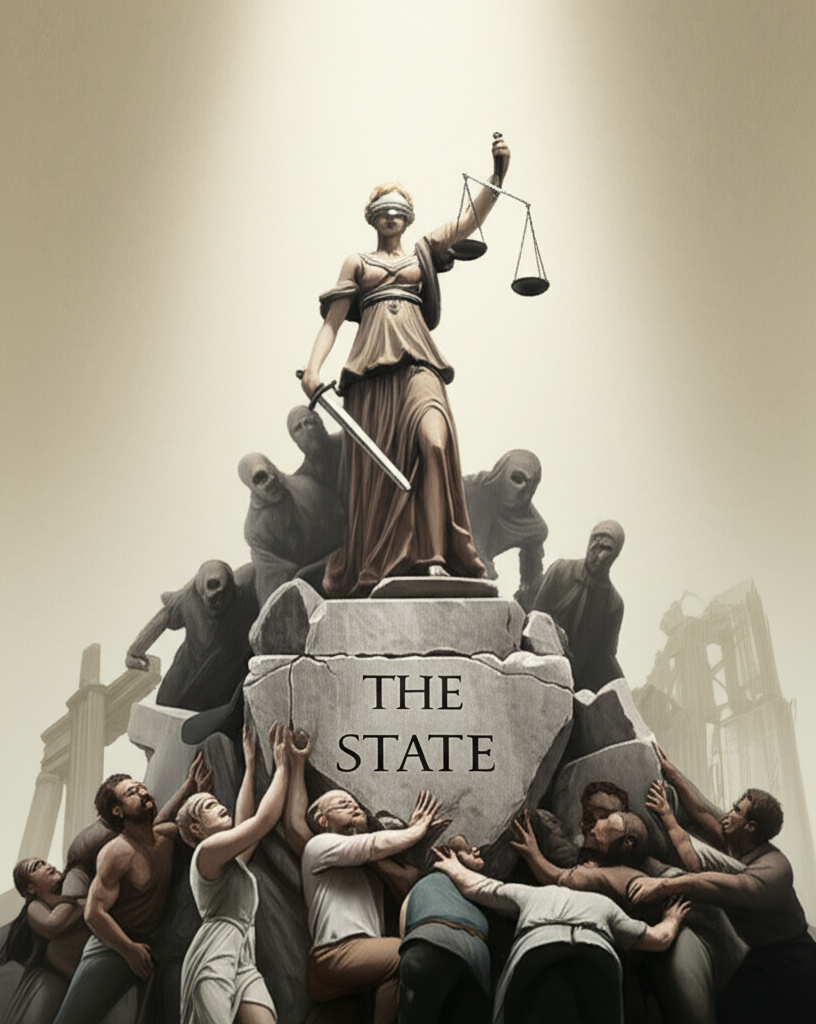

In the annals of human history, few concepts are as intertwined, yet as fraught with tension, as revolution and justice. At its core, this article posits that revolution, often a violent and disruptive upheaval, is frequently conceived and enacted as a desperate, ultimate measure to achieve justice where existing systems, particularly the State, have demonstrably failed. We will delve into the philosophical underpinnings drawn from the Great Books, exploring how thinkers from antiquity to modernity have grappled with the legitimacy and necessity of overthrowing established orders in pursuit of a more equitable world.

The Inherent Tension: When Justice Demands Change

The connection between revolution and justice is not merely incidental; it is often foundational. When a society or a State becomes so entrenched in injustice—be it economic disparity, political oppression, or systemic denial of rights—the very idea of justice itself can become a rallying cry for radical change. Philosophers have long debated whether such a rupture is ever justifiable, and if so, under what conditions.

- Plato's Vision of the Just State: In The Republic, Plato outlines an ideal State where justice is achieved through a harmonious balance of its parts, each performing its proper function. Deviation from this ideal, leading to tyranny or oligarchy, inherently represents injustice. While Plato did not explicitly advocate for popular revolution in the modern sense, his work implicitly suggests that a deeply unjust State is illegitimate and inherently unstable.

- Aristotle on the Causes of Stasis: Aristotle, in Politics, meticulously dissects the causes of political instability and revolution (stasis). He identifies inequality and injustice as primary drivers. When one group feels unfairly treated or deprived of its due share, or when rulers govern in their own interest rather than the common good, the seeds of rebellion are sown. For Aristotle, a State that fails to uphold a measure of distributive justice is ripe for overthrow.

The Social Contract and the Right to Revolution

The Enlightenment era brought forth explicit philosophical justifications for revolution as a means to restore justice, particularly against an oppressive State.

John Locke and the Consent of the Governed

John Locke's Second Treatise of Government is perhaps the most influential text in articulating a "right to revolution." Locke argues that government derives its legitimacy from the consent of the governed, forming a social contract to protect individuals' natural rights to life, liberty, and property.

- Breach of Trust: When the State (or the sovereign) acts contrary to the trust placed in it by the people—by infringing upon their rights or failing to protect them—it effectively dissolves the social contract.

- Return to Nature: In such a scenario, the people revert to a state of nature, regaining their inherent right to form a new government that will uphold justice. This was a profound philosophical justification for the American Revolution.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the General Will

Rousseau, in The Social Contract, similarly posits that legitimate government flows from the "general will" of the people. While he emphasizes civic participation and legislative power, his work also provides a framework for understanding when a State loses its legitimacy.

- Usurpation of Sovereignty: If the government (the executive) usurps the sovereignty of the people (the legislative), it becomes tyrannical.

- Reclaiming Liberty: The people, as the ultimate sovereign, have the right—and perhaps the duty—to reclaim their liberty and establish a government that truly reflects the general will, thereby restoring justice.

Revolution as the Engine of Historical Justice

Moving into the 19th century, thinkers like Karl Marx saw revolution not just as a right but as an inevitable historical force, driven by inherent contradictions within economic systems and the class struggle.

- Marx's Dialectical Materialism: In The Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels argue that history is a series of class struggles, with each epoch's dominant class eventually overthrown by the oppressed. The capitalist State, they contended, is merely an instrument of the ruling bourgeoisie, perpetuating injustice against the proletariat.

- Proletarian Revolution: For Marx, the ultimate revolution would be the overthrow of the capitalist State by the working class, leading to a classless society where true justice (in the form of economic equality and the abolition of exploitation) could finally be achieved. This vision sees revolution as a necessary, even violent, midwife for a new, more just historical stage.

The Paradox of Revolutionary Justice

The connection between revolution and justice is rarely straightforward. Revolutions, by their very nature, are disruptive and often violent, leading to temporary injustices and suffering. This raises a critical philosophical dilemma: can justice truly be born from actions that inherently involve injustice?

- Means and Ends: Is the pursuit of a greater justice sufficient to justify the often brutal means of revolution? This question has plagued philosophers and revolutionaries alike.

- The Problem of the Aftermath: Even successful revolutions can fail to deliver on their promise of justice, sometimes replacing one form of oppression with another. The challenge lies not just in overthrowing the unjust State, but in building a truly just one in its place.

Key Tensions in the Revolution-Justice Connection:

- Legitimacy vs. Illegitimacy: When does a State's injustice become so profound that revolution transitions from an illegitimate act of rebellion to a legitimate demand for justice?

- Violence vs. Peace: Can true justice ever be achieved through violent means, or does violence inherently corrupt the pursuit of justice?

- Individual vs. Collective Justice: Does revolutionary justice prioritize the collective good, potentially at the expense of individual rights, or vice-versa?

Conclusion: An Enduring Philosophical Debate

The connection between revolution and justice remains one of philosophy's most enduring and vital debates. From the ancient Greek city-states to modern global movements, the cry for justice has often been the spark that ignites revolution against an unresponsive or tyrannical State. While the path of revolution is fraught with peril and ethical complexities, history demonstrates that when the established order fails utterly to provide justice, humanity's inherent yearning for fairness can, and often does, lead to a demand for radical transformation. The question for each generation, then, is not whether revolution and justice are connected, but under what circumstances that connection becomes an imperative.

📹 Related Video: KANT ON: What is Enlightenment?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""John Locke Right to Revolution Explained""

📹 Related Video: KANT ON: What is Enlightenment?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Karl Marx Class Struggle and Revolution Summary""