The Enduring Connection: Unraveling Custom and Law in the Fabric of the State

The relationship between custom and law is not merely one of historical curiosity but a connection fundamental to the very architecture of human society and the legitimate functioning of the State. At its core, this intricate dance between unwritten social norms and codified legal statutes dictates how we live, govern ourselves, and define justice. Understanding this profound interdependency is crucial for anyone seeking to comprehend the philosophical underpinnings of social order, political legitimacy, and the evolution of governance. This pillar page delves into the historical evolution, philosophical discourse, and contemporary relevance of custom and law, drawing insights from the enduring wisdom contained within the Great Books of the Western World. We will explore how customs often precede, inform, and sometimes challenge formal laws, and how the State acts as both a product and a shaper of this dynamic relationship.

Defining the Terrain: Custom, Convention, and Law

To appreciate the connection, we must first delineate the distinct yet often overlapping concepts of custom, convention, and law. These terms represent different layers of social regulation, each playing a vital role in the cohesion of any community.

Custom: The Unwritten Architect of Society

Custom refers to a long-established practice or usage that, by its continuous observance, has acquired the force of an unwritten rule. It is organic, evolving naturally within a community, often without conscious design. Customs are deeply embedded in the cultural and moral fabric of a society, guiding behavior through social expectation and tradition rather than explicit command. Think of ancient tribal practices, rites of passage, or even common courtesies – these are the silent architects of social order.

Key Characteristics of Custom:

- Organic Growth: Develops naturally over time.

- Voluntary Adherence: Maintained by social pressure and tradition.

- Unwritten: Not formally codified.

- Community-Specific: Often varies greatly between different groups.

Law: The Formal Framework of the State

Law, in contrast, is a system of rules that a society or State creates and enforces to regulate the actions of its members. Laws are typically written, formally enacted, and backed by the coercive power of the State. They are deliberate creations, designed to achieve specific social, political, or economic objectives. From criminal codes to property rights, laws provide a formal, often rigid, structure for society.

Key Characteristics of Law:

- Deliberate Creation: Enacted by a recognized authority (legislature, sovereign).

- Binding Force: Enforceable through sanctions and the power of the State.

- Written: Codified and publicly accessible.

- Universal Application: Intended to apply equally to all within its jurisdiction.

Convention: Bridging the Gap

Convention often acts as a bridge or a broader category encompassing both custom and certain aspects of law. It refers to a widely accepted principle or rule that guides behavior, often based on common agreement or general consent. While customs are often unthinking traditions, and laws are explicit commands, conventions can be explicit agreements (like international treaties) or implicit understandings (like dress codes). In many ways, customs are a subset of conventions, and laws often formalize or codify conventions.

Philosophical Roots: Ancient Insights into the Nexus

The Great Books of the Western World offer profound insights into the foundational connection between custom and law, demonstrating that this dialogue is as old as philosophy itself.

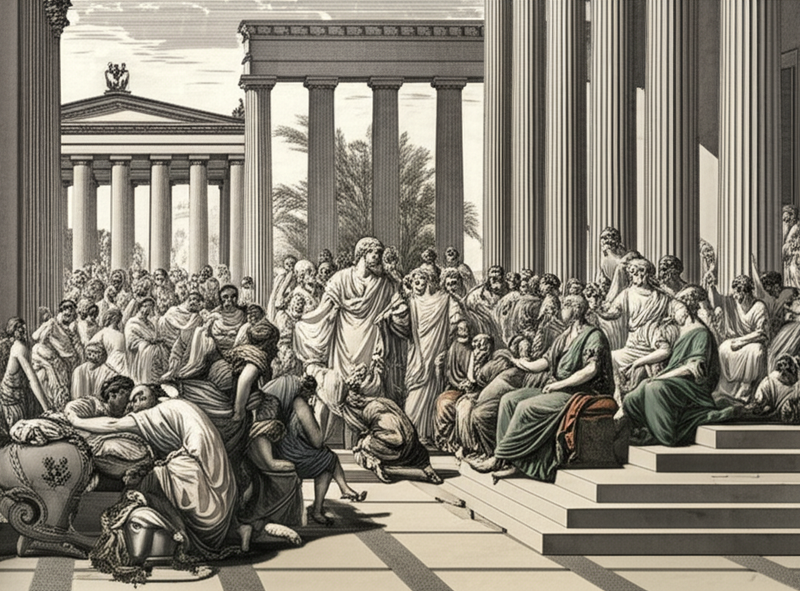

Aristotle and the Polis: Ethos as Foundation

For Aristotle, particularly in his Nicomachean Ethics and Politics, the character (ethos) of citizens, shaped by custom and habituation, was paramount to the well-being of the polis (city-state). He argued that good laws could only be effective if the citizens possessed good habits and virtues, which were primarily cultivated through custom and education. The laws of a State, therefore, were not merely external impositions but reflections of, and instruments for shaping, the community's established ways of life. Aristotle saw a natural progression where virtuous customs could inform just laws, leading to a flourishing society.

Plato's Ideal State and the Role of Tradition

While Plato, in his Republic and Laws, envisioned an ideal State governed by philosopher-kings and meticulously designed laws, he also implicitly acknowledged the role of existing traditions and the need for laws to gradually guide citizens towards an ideal ethos. His extensive discussions on education and the shaping of character underscore the understanding that laws cannot operate in a vacuum but must interact with the prevailing customs and moral sensibilities of the people.

The Evolution of Legal Thought: From Customary Practice to Codified Rule

The historical development of legal systems further illuminates the dynamic connection.

The Roman Jurists and Jus Gentium

Roman law, a cornerstone of Western jurisprudence, provides a clear example of custom's influence. While the Romans developed sophisticated codified laws (jus civile), they also recognized jus gentium – the law of nations – which was largely derived from customs and practices common to various peoples. This demonstrated an early understanding that certain universal principles, often rooted in common human customs, could transcend specific state laws.

Medieval Common Law: Custom as Precedent

The development of English Common Law, especially during the medieval period, is perhaps the most direct illustration of customary law's power. Common Law emerged not from legislative decree but from the decisions of judges who, in resolving disputes, often looked to local customs and established practices. These judicial decisions then became precedents (stare decisis), effectively formalizing custom into law. The State, through its courts, thus recognized and solidified the unwritten rules of the community.

The Enlightenment and the Social Contract: Rationalizing Law

The Enlightenment brought a new perspective to the connection, emphasizing reason and individual rights, yet still grappling with the legacy of custom.

Locke, Rousseau, and the Will of the People

Philosophers like John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, proponents of the social contract theory, argued that legitimate law derives its authority from the consent of the governed. While they focused on rational principles, this consent often implicitly or explicitly referred to the existing customs, values, and shared understandings of a people. For Rousseau, the "general will" that informed just laws was deeply intertwined with the moral and social customs of a community, shaping what was perceived as good and desirable for all. The State, in this view, was created to uphold these collective values and ensure liberty within a framework of law derived from the people's will.

Montesquieu: Climate, Mores, and Legislation

In The Spirit of the Laws, Montesquieu famously argued that laws should not be arbitrary but should be adapted to the particular "spirit" of a nation, which included its climate, religion, commerce, and, crucially, its mores and customs. He believed that laws were most effective when they harmonized with the established ways of life, recognizing the deep-seated connection between a people's traditions and the legal structures that govern them. Any attempt by the State to impose laws contrary to these deeply ingrained customs was likely to fail.

Modern Jurisprudence: The Dynamic Interplay

In the contemporary world, the connection between custom and law remains robust, albeit with new complexities.

International Law and Customary Norms

Even in the realm of international relations, customary international law plays a significant role. Practices consistently followed by States out of a sense of legal obligation (opinio juris) can evolve into binding international norms, demonstrating that customary practices among nations can transcend formal treaties and agreements.

Indigenous Law and Plural Legal Systems

Many modern States increasingly recognize and integrate indigenous customary laws into their broader legal frameworks. This acknowledges the unique cultural heritage and long-standing traditions of indigenous peoples, creating pluralistic legal systems where custom and formal law coexist, sometimes in harmony, sometimes in tension.

The State as Arbiter and Codifier

Today, the State often acts as the primary arbiter of custom. It can:

- Codify: Transform established customs into formal statutes.

- Legitimize: Grant legal recognition to existing customary practices.

- Reform: Amend or abolish customs deemed harmful or outdated.

- Enforce: Use its power to ensure adherence to laws, which may or may not align with all existing customs.

Tensions and Transformations: When Custom and Law Collide

While often complementary, the connection between custom and law is not without friction.

The Challenge of Harmful Customs

One of the most significant tensions arises when deeply entrenched customs conflict with universal human rights or modern ethical standards. Practices like child marriage, female genital mutilation, or caste discrimination, while historically customary in some societies, are increasingly challenged and outlawed by States and international bodies. Here, formal law often acts as a tool for social reform, seeking to override customs deemed unjust or harmful.

The Lag Between Custom and Law

Laws can sometimes lag behind evolving social customs. As societies change rapidly, new customs and social norms emerge (e.g., regarding digital privacy, LGBTQ+ rights). The legal system, often slow and deliberate, may struggle to keep pace, leading to a disconnect between what is socially accepted and what is legally sanctioned. This can create a sense of injustice or irrelevance for the law.

The Perils of Over-Codification

Conversely, an over-reliance on formal law to regulate every aspect of life can stifle the organic development of custom and community norms. When the State attempts to legislate too minutely, it can undermine the self-regulating capacity of communities and reduce the sense of shared responsibility that customs foster.

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Aristotle on Law and Justice" - Look for videos that discuss Aristotle's political philosophy, his views on natural law, and the role of habituation and character in the polis."

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""History of Common Law vs Civil Law" - Search for content explaining the origins and evolution of legal systems, focusing on how customary practices influenced common law traditions."

Concluding Reflections: The Enduring Dialogue

The connection between custom and law is a testament to the complex, evolving nature of human governance. Custom, born from the collective habits and shared values of a community, provides the bedrock upon which formal legal systems are often built. Law, in turn, provides the structure, clarity, and enforcement mechanism necessary for a large and diverse State to function effectively.

From the ancient polis to modern international relations, this dialogue between the unwritten and the written, the organic and the deliberate, continues to shape our societies. A truly just and stable State recognizes this intricate interdependency, understanding that while law must sometimes reform custom, it is most potent when it reflects and respects the deeper currents of a people's established ways. The ongoing challenge for governance is to navigate this connection wisely, balancing the need for stability and tradition with the imperative for progress and justice.