The Enduring Connection Between Beauty and Form

The pursuit of understanding beauty has captivated thinkers for millennia, often leading us back to its profound and often elusive connection with form. From the harmonious proportions of ancient architecture to the intricate patterns in nature, beauty frequently emerges not as a mere subjective whim, but as a response to discernible, underlying form. This article explores how Western philosophy, particularly through the lens of the Great Books of the Western World, has grappled with this fundamental connection, revealing form as an essential ingredient, if not the very essence, of what we perceive as beautiful, especially in art.

The Philosophical Roots: Beauty as Ideal Form

The idea that beauty is intrinsically linked to form finds its earliest and most influential expression in ancient Greek philosophy. For many, the very definition of beauty seemed to reside in qualities that could be described, measured, and understood through their structure.

Plato and the Realm of Perfect Forms

Perhaps no philosopher more profoundly shaped our understanding of form than Plato. In his dialogues, particularly in the Symposium and Phaedrus, Plato posits that earthly beauty is merely a pale reflection of transcendent, perfect Forms existing in an ideal realm. A beautiful object – a person, a vase, a melody – is beautiful precisely because it participates in the Form of Beauty itself.

- The Ideal: The

Formof Beauty is eternal, unchanging, and perfect. - The Manifestation: Particular beautiful things in our world derive their

beautyby imperfectly mirroring this idealForm. - The Connection: Our appreciation of

beautyis, in essence, a recognition of this underlying, perfectFormshining through the material.

For Plato, the form of something isn't just its shape, but its essential nature, its ideal blueprint. Art, in this context, when it strives for beauty, is attempting to capture or evoke these ideal Forms, even if it is an imitation of an imitation.

Aristotle's Immanent Form and Purpose

Aristotle, while diverging from Plato's transcendent Forms, nonetheless emphasized the critical role of form in beauty. For Aristotle, form is not separate from matter but is immanent within it, giving shape and purpose (telos) to an object. In his Poetics and Metaphysics, he suggests that beauty arises from qualities like order, symmetry, and a definite magnitude – all aspects of form.

- Wholeness and Unity: A beautiful object possesses internal coherence, where all its parts contribute to a unified whole.

- Proportion and Harmony: The relationships between the parts are balanced and pleasing.

- Magnitude: The object is neither too large to be grasped as a whole nor too small to be appreciated in its detail.

Aristotle's perspective grounds beauty more firmly in the observable world, asserting that the inherent form of a thing, when well-executed and purposeful, naturally leads to beauty.

Medieval Synthesis: Clarity, Integrity, Proportion

The medieval period, notably through thinkers like Thomas Aquinas (drawing heavily on Aristotle), continued to refine the connection between beauty and form. Aquinas, in his Summa Theologica, identified three conditions for beauty:

| Element of Beauty | Description | Connection to Form |

|---|---|---|

| Integrity | Wholeness or perfection; nothing lacking. | The complete and unified form of the object. |

| Proportion | Harmony or right ordering of parts. | The internal form and relational structure of the object's components. |

| Clarity | Radiance or brilliance; the object's essence shining through. | The manifest form making its inherent nature intelligible and perceptible. |

These elements clearly underscore how beauty is perceived when the form of an object is complete, well-ordered, and clearly expressed. The form isn't just a container; it's the very structure that allows beauty to emerge.

Modern Perspectives and the Role of Art

Even as philosophical thought evolved, introducing concepts of subjective taste (e.g., Kant's Critique of Judgment), the underlying connection between beauty and form persisted. While Kant emphasized the "disinterested pleasure" derived from beauty, this pleasure often still arises from a perception of "purposiveness without purpose" – an appreciation of form that seems intrinsically well-designed, even if it serves no practical end.

Art as the Embodiment of Form and Beauty

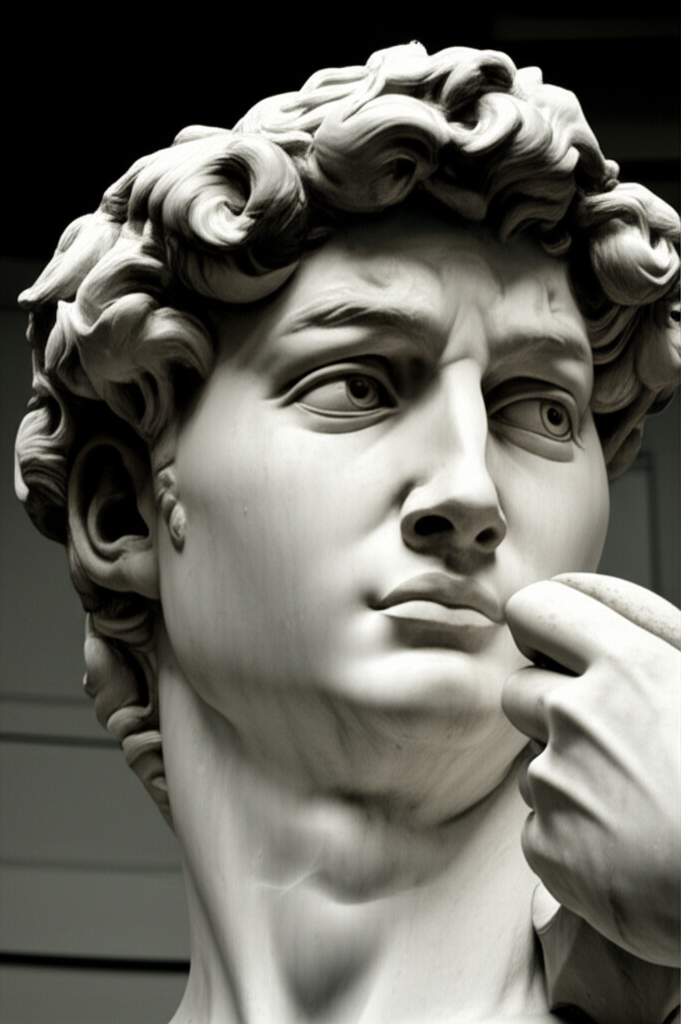

Art serves as a powerful testament to this enduring connection. From the sculptural perfection of Michelangelo's David, where the human form is rendered with divine beauty through meticulous proportion and detail, to the architectural grandeur of a Gothic cathedral, whose intricate forms reach skyward in a symphony of light and shadow, art consistently explores and celebrates the interplay of these concepts.

Even in abstract art, where representational forms are eschewed, the connection remains. Abstract painters and sculptors often explore beauty through the pure manipulation of line, shape, color, and texture – fundamental elements of form. The arrangement of these elements, their balance, rhythm, and contrast, create a new kind of form that evokes aesthetic pleasure.

Consider the following ways art illuminates this connection:

- Classical Sculpture: Emphasizes ideal human

form, proportion, and symmetry to achievebeauty. - Renaissance Painting: Utilizes perspective, composition, and anatomical accuracy to create harmonious and beautiful

forms. - Architecture: Manipulates spatial

form, structuralform, and decorativeformto create aesthetically pleasing and functional spaces. - Abstract Art: Explores the inherent

beautyin pureform– geometric shapes, organic lines, and color relationships.

Conclusion: An Enduring Dialogue

The connection between beauty and form is not a simple equation but a rich, ongoing dialogue that has shaped Western thought for millennia. From Plato's transcendent ideals to Aristotle's immanent structures, and through the meticulous analyses of medieval and modern philosophers, the consensus remains: beauty is often, if not always, rooted in the apprehension of form. Whether it's the form of an ideal, the inherent structure of an object, or the deliberate construction in art, our aesthetic appreciation is deeply tied to how form is manifested, organized, and perceived. To truly understand beauty, we must learn to see and appreciate the form from which it springs.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Plato's Theory of Forms Explained"

-

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "The Philosophy of Beauty and Aesthetics"