The Enduring Nexus: Exploring the Connection Between Beauty and Form

The pursuit of understanding beauty has captivated philosophers for millennia, often leading us to a profound realization: beauty is not merely a subjective sensation, but is inextricably linked to Form. From the classical ideals of ancient Greece to the intricate compositions of modern Art, the connection between an object's structure, arrangement, and inherent grace remains a cornerstone of aesthetic inquiry. This article delves into how philosophers, particularly those whose works comprise the Great Books of the Western World, have illuminated this fundamental relationship, revealing that Form is often the very architecture of Beauty.

Ancient Foundations: Plato and the Ideal Form

For many of us, the concept of Beauty feels intuitive, an immediate response to something pleasing. However, ancient Greek thinkers, particularly Plato, challenged us to look beyond the surface. In his dialogues, Plato introduces the revolutionary idea of Forms (or Ideas) as the ultimate reality, existing independently of the physical world. For Plato, true Beauty is not found in a fleeting sunset or a perfectly sculpted statue, but in the eternal, unchanging Form of Beauty itself.

- The World of Forms: Our physical world, with all its beautiful objects, is merely an imperfect reflection or "participation" in these perfect, non-physical Forms.

- Beauty as Participation: A beautiful person, a beautiful melody, or a beautiful piece of Art is beautiful precisely because it partakes, however dimly, in the Form of Beauty.

- The Connection: Here, the connection is profound: Form is not just a characteristic of beauty; it is the essence of beauty, with physical manifestations being mere shadows. The structured, harmonious aspects we perceive in beautiful things are echoes of a higher, perfect Form.

Plato's philosophy, deeply explored in works like The Symposium and The Republic, suggests that our aesthetic appreciation is, in essence, a recollection of these divine Forms.

Aristotle's Empirical Perspective: Order, Proportion, and Wholeness

While Plato ascended to the realm of ideal Forms, his student Aristotle brought philosophy back down to earth, focusing on the observable world. For Aristotle, Beauty was not a transcendental entity, but an immanent quality found within objects themselves, discernible through our senses and intellect. Yet, even in this empirical approach, Form remained central.

Aristotle's analysis of beauty, particularly in Poetics and Metaphysics, emphasizes specific qualities that contribute to it:

- Order (Taxis): A harmonious arrangement of parts.

- Proportion (Symmetria): The correct relationship of parts to each other and to the whole.

- Definite Magnitude (Horismenon Megethos): Being neither too large nor too small, allowing the whole to be grasped.

These qualities are, fundamentally, attributes of Form. A beautiful object possesses a well-defined Form that exhibits these characteristics. The connection here is that Beauty is the perceptual experience of a well-ordered and proportioned Form.

Table: Contrasting Platonic and Aristotelian Views on Beauty and Form

| Aspect | Plato (Idealist) | Aristotle (Empiricist) |

|---|---|---|

| Locus of Beauty | Transcendent, in the Form of Beauty | Immanent, in the object itself |

| Role of Form | The essence of Beauty; objects participate | The structure embodying qualities like order/proportion |

| Perception | Recollection of ideal Forms | Sensory and intellectual apprehension of qualities |

| Connection | Beauty is the Form | Beauty arises from well-structured Form |

The Role of Art: Crafting Form, Revealing Beauty

The realm of Art provides perhaps the most tangible evidence of the connection between Beauty and Form. Artists, whether painters, sculptors, architects, or musicians, are essentially manipulators of Form. They arrange lines, colors, sounds, and masses to create structures that evoke aesthetic responses.

Consider the Renaissance masters, whose works are deeply embedded in the Great Books tradition of humanism and classical revival. They meticulously studied anatomy, perspective, and composition – all aspects of Form – to achieve breathtaking Beauty.

- Sculpture: The balanced musculature and elegant posture of a classical statue owe their Beauty to their carefully sculpted Form.

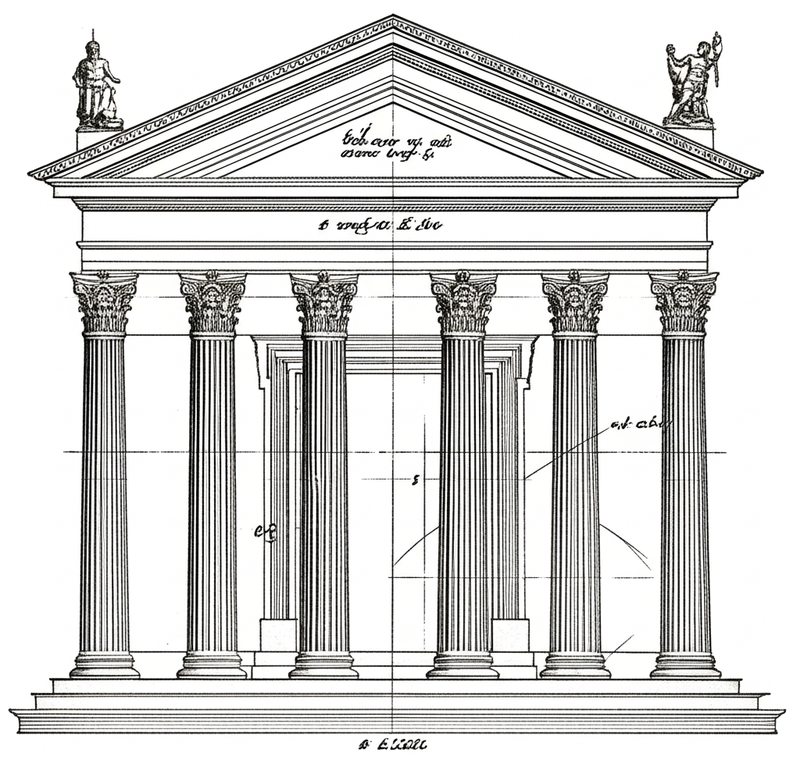

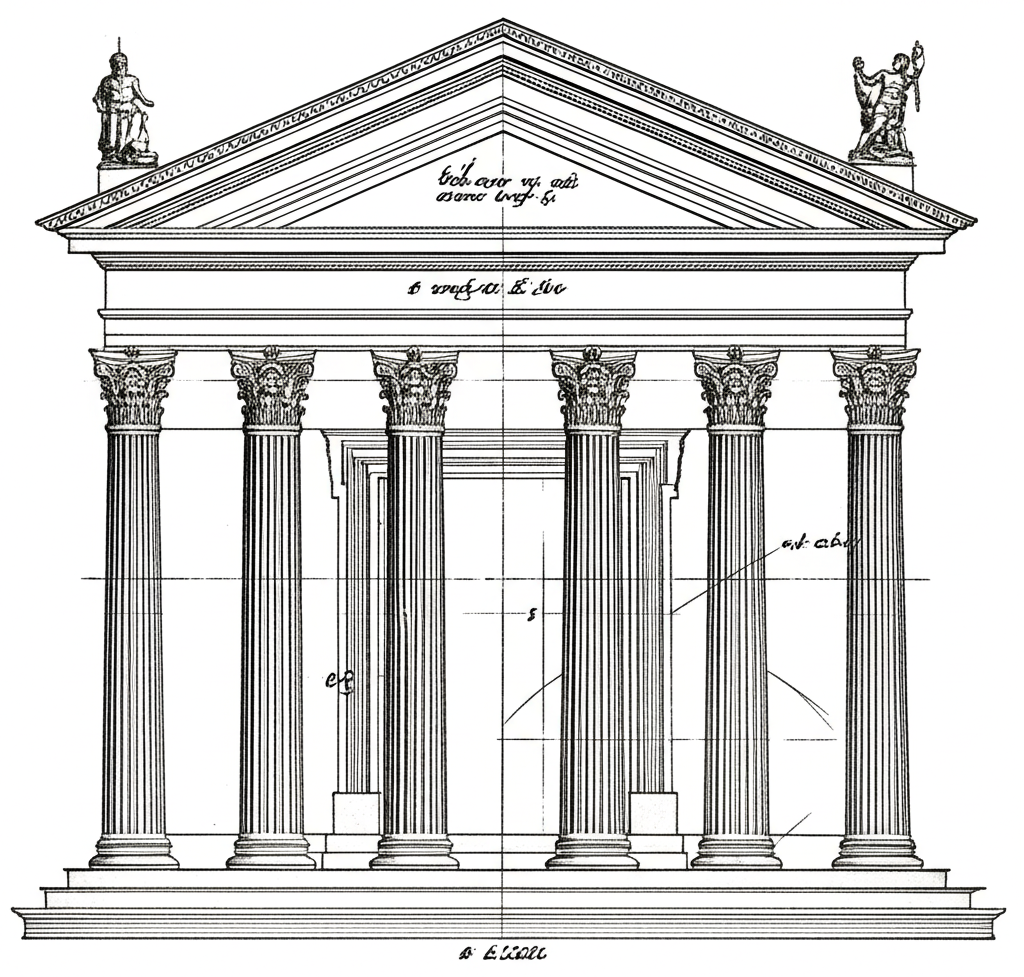

- Architecture: The harmonious proportions, symmetry, and rhythmic repetition in a building's design are what elevate it from mere shelter to a work of Art.

- Painting: Composition, the arrangement of elements within the frame, is a fundamental aspect of Form that guides the viewer's eye and creates aesthetic impact.

In each instance, the artist's mastery of Form is what unlocks the object's potential for Beauty. The connection is not coincidental; it is foundational to the creation and appreciation of Art.

Enduring Resonance: The Universal Language of Form

The philosophical inquiry into the connection between Beauty and Form is not confined to ancient texts; it resonates through subsequent philosophical and artistic movements. From the neo-Platonists to Kant's critiques of aesthetic judgment, and even into modern theories of Art, the dialogue continues. What remains constant is the recognition that Form provides the framework, the structure, and often the very definition within which Beauty can manifest and be apprehended. Whether seen as an echo of a divine ideal or an emergent property of harmonious design, Form is the silent language through which Beauty speaks to us across cultures and centuries.

YouTube video suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Plato Symposium Beauty Forms Philosophy Explained"

2. ## 📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Aristotle Poetics Aesthetics Form Proportion Art"