The Enduring Enigma: Exploring the Concept of the Soul in Ancient Philosophy

The question of the Soul stands as one of the most profound and persistent inquiries in the history of Philosophy. From the earliest stirrings of rational thought to the sophisticated systems of Plato and Aristotle, ancient thinkers grappled with its nature, origin, and destiny. This pillar page delves into the multifaceted concept of the soul as understood by the foundational minds of antiquity, revealing how their diverse perspectives shaped not only subsequent philosophical discourse but also our very understanding of Being and human nature. We will journey through the Pre-Socratics' initial material explorations, the revolutionary insights of Socrates and Plato, Aristotle's rigorous empirical analysis, and the varied interpretations of later Hellenistic schools, ultimately showcasing the enduring legacy of their Metaphysics on Western thought.

I. The Primordial Question: What is the Soul?

Before diving into specific theories, it's crucial to understand the broad scope of what "soul" (ψυχή, psychē) encompassed in ancient thought. Far from being a mere religious construct, the soul was considered the animating principle of life itself – the source of movement, sensation, thought, and emotion. It was often seen as the essence of a living being, that which distinguished the living from the dead. The inquiry into the soul was, therefore, not just a matter of spirituality, but a fundamental aspect of biology, psychology, ethics, and Metaphysics. How could something so intangible, yet so central to our experience of Being, be understood? This was the challenge that defined much of ancient Philosophy.

II. Whispers of the Soul: Pre-Socratic Explorations

Long before the classical Athenian period, the earliest Greek philosophers, often called the Pre-Socratics, began to speculate about the nature of the soul. Their approaches were diverse, often tied to their theories about the fundamental substance of the cosmos.

Early Materialist Views

- Thales (c. 624 – c. 546 BCE): Believed that "all things are full of gods," suggesting an animating force even in inanimate objects, and that magnets possess a soul because they can move iron. For him, the soul might have been a subtle, life-giving aspect of water, his primary element.

- Anaximenes (c. 586 – c. 526 BCE): Proposed air as the primary substance. He likened the soul to air, stating, "Just as our soul, being air, holds us together, so breath and air encompass the whole world." This implied a material, yet vital, connection between the individual soul and the cosmic breath.

- Heraclitus (c. 535 – c. 475 BCE): Saw fire as the fundamental element, representing constant flux and change. He believed the soul was akin to fire – dry, hot, and rational. A "dry soul" was the wisest and best, while a "wet soul" indicated intoxication or irrationality.

The Pythagoreans and the Immortality of the Soul

A significant departure came with Pythagoras (c. 570 – c. 495 BCE) and his followers. Influenced by Orphic traditions, the Pythagoreans introduced the radical idea of the soul's immortality and its transmigration (metempsychosis) through different bodies, human and animal. For them, the soul was distinct from the body, divine in origin, and subject to a cycle of purification. This concept laid crucial groundwork for later Platonic thought, emphasizing the soul's spiritual nature and its journey beyond mere corporeal existence.

Empedocles' Elemental Soul

Empedocles (c. 494 – c. 434 BCE), known for his theory of the four elements (earth, air, fire, water) and two cosmic forces (Love and Strife), also theorized about the soul. He believed the soul was composed of these four elements, and that it could perceive objects because it contained elements similar to those in the external world. The soul, for Empedocles, was not immortal in the Pythagorean sense, but rather subject to the cosmic cycle of combination and dissolution.

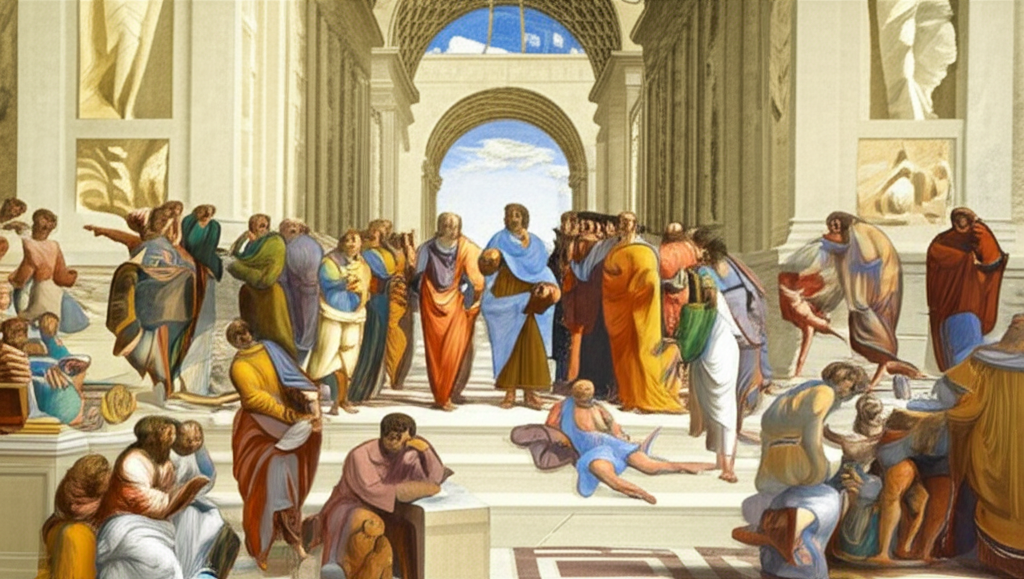

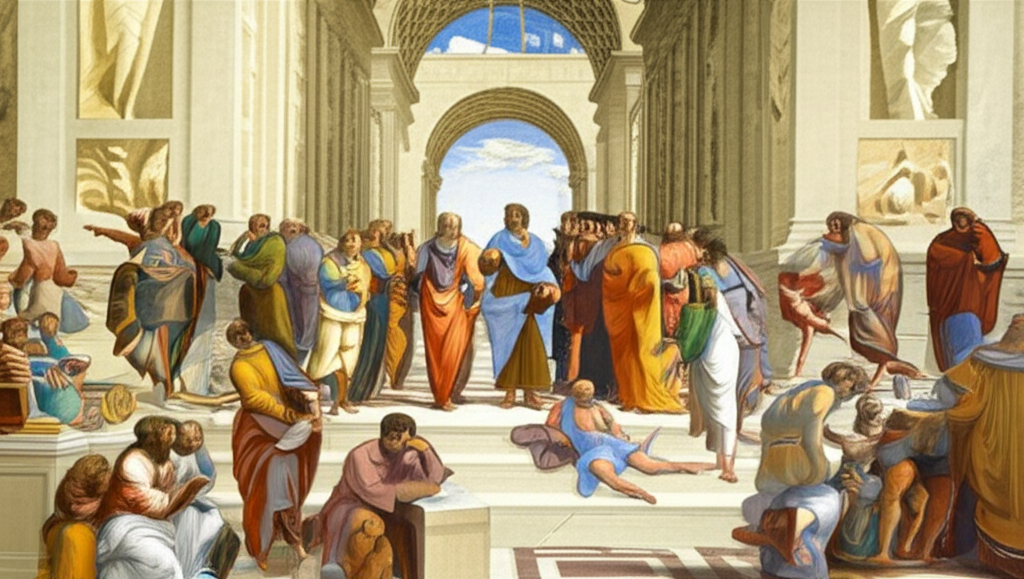

III. The Socratic-Platonic Revolution: Soul as the Seat of Reason and Immortality

The classical period witnessed a profound shift in the understanding of the soul, largely due to Socrates and his most famous student, Plato.

Socrates: "Know Thyself" and the Care of the Soul

Though Socrates (c. 470 – 399 BCE) wrote nothing himself, his teachings, as recorded by Plato, mark a pivotal moment. Socrates famously asserted that "the unexamined life is not worth living," emphasizing that the most crucial task for humans is the care of the soul. For Socrates, the soul was the true self, the seat of character, intellect, and moral judgment. He believed that virtue was knowledge, and vice was ignorance, implying that a well-ordered, rational soul was essential for a good life. He posited that the soul, being divine and intellectual, was superior to the body and capable of discerning universal truths.

Plato: The Tripartite Soul and the Realm of Forms

Plato (c. 428 – c. 348 BCE), deeply influenced by Socrates and the Pythagoreans, developed a comprehensive theory of the soul, central to his entire philosophical system. In works like the Phaedo, Republic, and Timaeus, he articulated the soul's nature, its relation to the body, and its destiny.

Key Platonic Concepts of the Soul:

- Immortality: Plato argued passionately for the soul's immortality. In the Phaedo, he presents several arguments, including the argument from recollection (that learning is remembering innate knowledge of Forms) and the argument from opposites (life comes from death). The soul, being akin to the eternal Forms, cannot perish.

- Tripartite Structure: In the Republic, Plato famously divides the soul into three distinct parts, analogous to the three classes in his ideal state:

- Rational Part (λογιστικόν, logistikon): Located in the head, this is the divine, immortal part, responsible for reason, wisdom, and the pursuit of truth. It should govern the other parts.

- Spirited Part (θυμοειδές, thumoeides): Located in the chest, this is the mortal part associated with emotions like anger, courage, honor, and ambition. It acts as an ally to reason.

- Appetitive Part (ἐπιθυμητικόν, epithumetikon): Located in the belly/lower torso, this is also mortal and deals with bodily desires such as hunger, thirst, and sexual urges. It needs to be controlled by reason.

Plato's Tripartite Soul

| Part of the Soul | Function | Virtue | Location | Analogy (Republic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rational | Reason, intellect, wisdom | Wisdom | Head | Philosopher King |

| Spirited | Emotion, courage, honor | Courage | Chest | Guardians |

| Appetitive | Desires, bodily urges, pleasure | Temperance/Moderation | Belly/Lower Torso | Producers |

For Plato, true justice and happiness (εὐδαιμονία, eudaimonia) in an individual arise when the rational part of the soul rules the spirited and appetitive parts, achieving internal harmony. The soul, in its highest form, strives to ascend from the sensory world to grasp the eternal Forms, revealing its deep connection to Metaphysics and the nature of ultimate Being.

IV. Aristotle's Empirical Lens: The Soul as the Form of the Body

Plato's most brilliant student, Aristotle (384 – 322 BCE), offered a radically different, yet equally influential, account of the soul. Moving away from his teacher's dualism and emphasis on separate Forms, Aristotle adopted a more biological and empirical approach, primarily articulated in his seminal work, De Anima (On the Soul).

Aristotle rejected the idea of the soul as a separate, independently existing entity that merely inhabits a body. Instead, he proposed that the soul is the form or essence of a living body. His famous definition states: "The soul is the first actuality of a natural body having life potentially within it."

Key Aristotelian Concepts of the Soul:

- Hylomorphism: For Aristotle, every substance is a composite of matter (body) and form (soul). The soul is not a distinct substance but rather the organizing principle, the structure, and the function of the body. Just as the shape of an axe is its form, enabling it to cut, the soul is the form of the body, enabling it to live, perceive, and think. They are inseparable.

- Hierarchical Faculties: Aristotle identified a hierarchy of soul faculties, corresponding to different levels of life:

- Nutritive Soul (Vegetative Soul): The most basic form, responsible for growth, reproduction, and nourishment. Found in plants, animals, and humans.

- Sensitive Soul (Appetitive Soul): Possesses the nutritive faculties plus sensation (perception) and locomotion. Found in animals and humans.

- Rational Soul (Intellectual Soul): The highest form, unique to humans. It encompasses the nutritive and sensitive faculties, plus the capacity for thought, reason, and deliberation. This is the part that allows us to engage in Philosophy and understand Metaphysics.

Aristotle's Hierarchy of Souls

| Type of Soul | Characteristics | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Nutritive | Growth, nutrition, reproduction | Plants |

| Sensitive | Nutritive + Sensation, desire, locomotion | Animals |

| Rational | Nutritive + Sensitive + Reason, thought, deliberation | Humans |

The Question of Immortality

Aristotle's view of the soul as the form of the body presented a challenge to the concept of immortality. If the soul is inseparable from the body, then it would seem to perish with the body. However, in De Anima, Aristotle hints at a possible exception for the active intellect (νοῦς ποιητικός, nous poietikos) – the highest part of the rational soul. He describes it as "separable, impassible, unmixed, being in essence activity." This enigmatic statement has led to centuries of debate among scholars, some interpreting it as a path to individual immortality, others as a reference to a universal, impersonal intellect that survives the individual. Regardless, Aristotle's profound analysis grounded the discussion of the soul firmly in the realm of natural Being and empirical observation.

V. Beyond Athens: Diverse Ancient Perspectives

The rich debates between Plato and Aristotle set the stage for subsequent philosophical schools, each developing its own unique understanding of the soul.

Stoicism: The Soul as Pneuma

The Stoics, founded by Zeno of Citium (c. 334 – c. 262 BCE), believed in a material universe permeated by a divine, rational principle called logos. The human soul, for the Stoics, was a fragment of this universal logos, a material substance called pneuma (a subtle fiery breath). It was considered rational, mortal, and divisible into eight parts (the ruling faculty, five senses, speech, and reproduction). The goal of Stoic Philosophy was to live in accordance with nature and reason, cultivating virtue and achieving apatheia (freedom from passion), thereby aligning one's individual pneuma with the cosmic logos. While generally considered mortal, some Stoics believed the soul might survive the body for a period before being reabsorbed into the cosmic fire.

Epicureanism: The Soul as a Collection of Atoms

Epicurus (341 – 270 BCE), building on the atomist theories of Democritus, held a thoroughly materialistic view of the soul. He taught that the soul was composed of very fine, smooth atoms dispersed throughout the body. These atoms were responsible for sensation and thought. When the body died, the soul-atoms dispersed, meaning the soul was inherently mortal. For Epicurus, this understanding was liberating: there was no afterlife to fear, and the goal of life was to achieve ataraxia (tranquility) and aponia (freedom from pain) through a simple, virtuous life, free from fear of death or divine punishment. His Metaphysics provided a foundation for a life focused on present well-being.

Neoplatonism: The Soul's Ascent to the One

Centuries later, Plotinus (c. 204 – 270 CE), the founder of Neoplatonism, revitalized and reinterpreted Plato's ideas, creating a highly influential mystical and metaphysical system. For Plotinus, the soul was an emanation from the divine "One" (the ultimate source of all Being), mediating between the intelligible world and the material world. The human soul, though fallen into a body, retains a longing for its divine origin. It is immortal and capable of purification and ascent back to the One through intellectual and spiritual contemplation. Plotinus's Philosophy profoundly influenced early Christian thought and medieval Metaphysics, emphasizing the soul's transcendent nature and its potential for union with the divine.

VI. The Enduring Legacy: Why the Ancient Soul Still Matters

The ancient Greek philosophers, from the early materialists to the sophisticated Platonists and Aristotelians, laid the groundwork for virtually every subsequent inquiry into the Soul. Their diverse theories reveal a profound engagement with questions that remain central to Philosophy today: What is consciousness? What is the nature of personal identity? Is there life after death? What is the relationship between mind and body?

Their contributions, preserved in the "Great Books of the Western World," continue to provoke thought and inspire debate. Whether viewed as an immortal, divine essence, the functional form of a living body, a material breath, or a collection of atoms, the concept of the soul has been an indispensable tool for understanding human Being, morality, and our place in the cosmos. The ancient quest to understand the soul is, in essence, the timeless human quest for self-knowledge and meaning, a journey that continues to unfold in the ever-evolving landscape of Metaphysics and modern thought.

Conclusion

The concept of the soul in ancient Philosophy is a rich tapestry woven from diverse threads of speculation, observation, and profound insight. From the elemental theories of the Pre-Socratics to Plato's eternal Forms and Aristotle's immanent forms, and onward to the practical ethics of the Stoics and Epicureans, and the mystical heights of Neoplatonism, ancient thinkers relentlessly pursued the fundamental questions surrounding human Being. Their enduring legacy reminds us that the inquiry into the Soul is not merely an academic exercise, but a deeply personal and universal journey into the essence of what it means to be alive, to think, to feel, and to exist within the grand scheme of Metaphysics.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Phaedo Summary and Analysis""

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Aristotle De Anima Explained""