The Enduring Enigma: Exploring the Soul in Ancient Philosophy

The question of what animates us, what constitutes our essential self, has fascinated humanity since time immemorial. Ancient philosophy, particularly that of the Greeks and Romans, grappled profoundly with this concept, developing diverse and often conflicting theories about the nature of the soul. This pillar page delves into the rich tapestry of ancient thought, tracing the evolution of the soul's definition from a mere life-force to an immortal, rational essence, and demonstrating its foundational role in Western metaphysics and our understanding of being. By examining the perspectives of key thinkers from Homer to the Hellenistic schools, we uncover how these foundational ideas shaped not only subsequent philosophical inquiry but also religious and scientific thought. Prepare to embark on a journey into the very core of ancient human understanding, exploring what it meant to possess a soul.

Early Conceptions: The Psyche as Life-Force and Breath

In the earliest Greek traditions, the soul (psyche) was often understood in a much more rudimentary sense than modern interpretations. Homeric epics, for instance, portray the psyche primarily as the breath of life, departing the body at the moment of death. It was a shadowy, insubstantial entity that resided in the underworld, largely devoid of personality or conscious agency. This early conception highlights a primal connection between life and breath, a tangible manifestation of being that animated the body.

The Pre-Socratic philosophers began to imbue the psyche with more complex properties, often linking it to fundamental cosmic elements:

- Thales: Suggested that the soul was a moving force, even attributing souls to magnets due to their power to move iron.

- Anaximenes: Proposed that the soul was made of air, a subtle and pervasive substance, connecting human life to the very atmosphere.

- Heraclitus: Spoke of the soul as fiery and dry, believing that a dry soul was the wisest, capable of discerning the universal logos.

- Empedocles: Conceived of the soul as a mixture of the four elements (earth, air, fire, water), constantly seeking harmony.

These early thinkers, while diverse in their conclusions, shared a common thread: the soul was intrinsically linked to the physical world, a principle of animation that explained life and movement, rather than an entirely separate, spiritual entity.

Socrates and Plato: The Soul as the Seat of Reason and Morality

The true revolution in the concept of the soul arrived with Socrates and his most famous student, Plato. For them, the soul transcended mere life-force; it became the very essence of human identity, the seat of intellect, morality, and personality.

Socrates famously proclaimed that "the unexamined life is not worth living," emphasizing the paramount importance of caring for one's soul. He believed the soul was the intellectual and moral core of a person, distinct from the body, and the true self. For Socrates, virtue was knowledge, and the pursuit of wisdom was the ultimate purification of the soul.

Plato, building upon Socratic insights, developed a highly sophisticated and influential theory of the soul that became a cornerstone of Western metaphysics. He argued for the immortality of the soul and its tripartite nature, as detailed in works like The Republic and Phaedo.

Plato's Tripartite Soul

| Part of the Soul | Location (Metaphorical) | Function | Virtue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reason (λογιστικόν) | Head | Seeks truth, governs the other parts | Wisdom |

| Spirit (θυμοειδές) | Chest | Seeks honor, courage, assists reason | Courage |

| Appetite (ἐπιθυμητικόν) | Belly/Lower Body | Seeks bodily pleasures (food, drink, sex) | Moderation |

Plato believed that a just individual, and a just society, achieved harmony when Reason governed the Spirit and Appetite. Furthermore, for Plato, the soul was not only immortal but also pre-existent, having once dwelled in the realm of the Forms, where it apprehended perfect knowledge. Learning, therefore, was a process of recollection (anamnesis) – remembering the truths the soul already knew. This dualistic view, separating the eternal soul from the perishable body, profoundly influenced subsequent philosophical and theological traditions.

Aristotle: The Soul as the Form of the Body

Aristotle, Plato's most famous student, offered a strikingly different, yet equally influential, perspective on the soul. In his seminal work De Anima (On the Soul), Aristotle rejected Plato's radical dualism, arguing instead for a more integrated view. For Aristotle, the soul (psyche) was not a separate entity inhabiting the body but rather the form or first actuality of a natural body that has life potentially.

This means the soul is to the body what the shape is to a statue, or the function is to an eye. It is the organizing principle, the essence that makes a body a living being. The soul is what gives a living thing its characteristic activities and properties.

Aristotle's Hierarchy of Souls

Aristotle identified a hierarchy of souls, each possessing the capacities of the lower forms:

- Nutritive Soul (Plants): Responsible for growth, reproduction, and nourishment.

- Sensitive Soul (Animals): Possesses the capacities of the nutritive soul, plus sensation, desire, and self-motion.

- Rational Soul (Humans): Possesses the capacities of the sensitive soul, plus the unique ability to reason, think, and engage in intellectual activity.

For Aristotle, the soul and body are two aspects of a single being. While he allowed for the possibility that the highest part of the rational soul (the "active intellect") might be separable and immortal, his primary focus was on the soul's function within the living organism. His approach provided a biological and empirical foundation for understanding the soul, deeply impacting later scientific and philosophical inquiries into life and consciousness.

Hellenistic Perspectives: Stoics, Epicureans, and Skeptics

Following the classical period, Hellenistic schools of philosophy continued to debate the nature of the soul, often with a focus on its implications for ethics and human tranquility.

Hellenistic Views on the Soul

| School | Key Concept of the Soul | Immortality? | Ethical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stoicism | Pneuma (fiery breath), a material substance, part of the divine logos | Generally mortal, though some believed it could survive briefly after death. | Focus on living in accordance with reason and nature; apathy (freedom from passion). |

| Epicureanism | Collection of fine, smooth atoms, dispersed at death. | Absolutely mortal. | Seek pleasure (absence of pain) and tranquility; avoid fear of death. |

| Skepticism | Questioned the possibility of certain knowledge about the soul. | Undecidable. | Suspension of judgment (epochē) leads to tranquility (ataraxia). |

These schools, while diverging in their conclusions, collectively shifted the emphasis from the metaphysical nature of the soul itself to its practical implications for human flourishing and ethical conduct. Whether the soul was material or immaterial, mortal or immortal, the central concern was how understanding it could lead to a good life.

The Enduring Legacy of Ancient Soul Concepts

The diverse and profound inquiries into the soul by ancient philosophers laid the essential groundwork for millennia of Western thought. From the earliest breath-soul to Plato's eternal Forms and Aristotle's integrated essence, these concepts shaped not only philosophy but also theology, science, and psychology. The ancient debates about the soul's nature, its relation to the body, its mortality, and its capacity for reason continue to resonate, informing contemporary discussions on consciousness, artificial intelligence, and the very definition of human being.

Key Takeaways

- Evolution of Concept: The soul evolved from a simple life-force (Homer, Pre-Socratics) to the core of identity and reason (Socrates, Plato), and then to the animating form of the body (Aristotle).

- Metaphysical Significance: Ancient discussions of the soul were central to understanding metaphysics, particularly the nature of reality, existence, and the relationship between mind and matter.

- Ethical Foundation: For many ancient philosophers, particularly Socrates, Plato, and the Hellenistic schools, understanding the soul was crucial for living a virtuous and fulfilling life.

- Diverse Views: There was no single, unified concept of the soul in ancient philosophy, but rather a rich spectrum of ideas that often stood in stark contrast to one another.

Explore Further

The journey into the concept of the soul in ancient philosophy is a deep dive into the very foundation of Western thought. Each philosopher offers a unique lens through which to view human existence and our place in the cosmos. We encourage you to delve deeper into the primary texts and engage with these profound ideas.

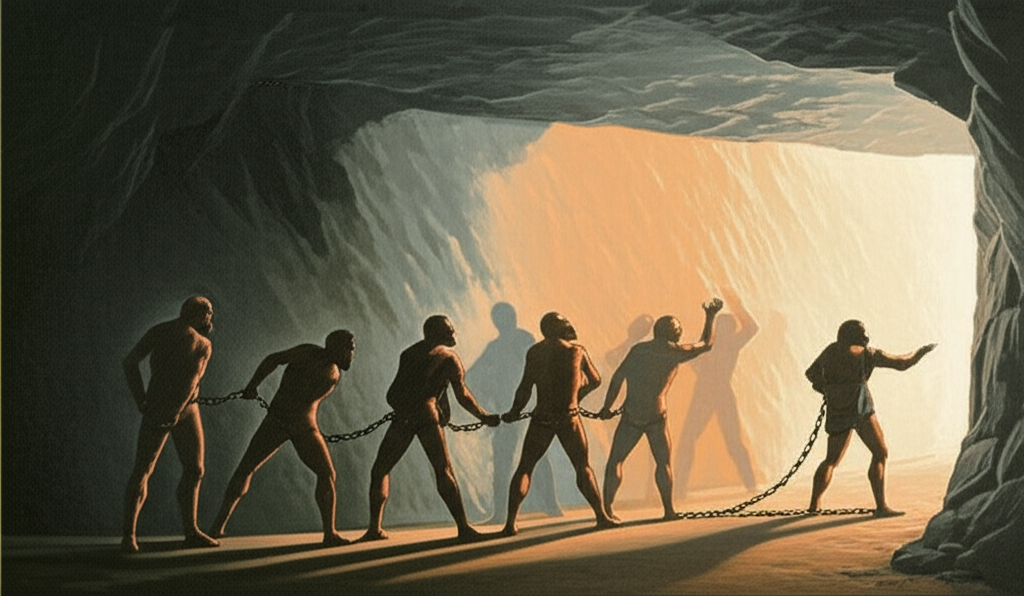

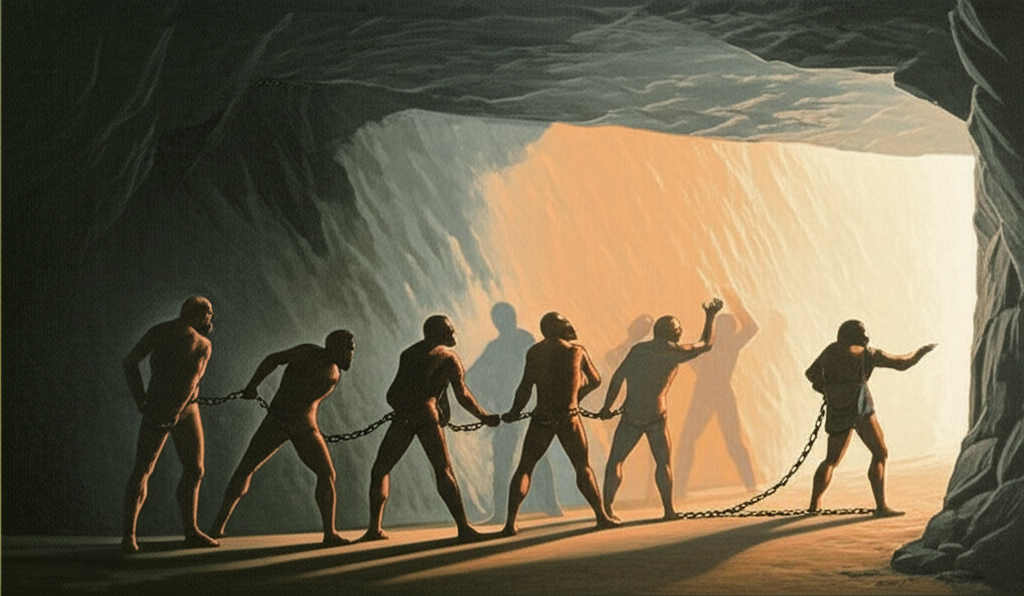

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Plato's Theory of the Soul Explained"

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Aristotle De Anima Summary"