The Perennial Conundrum: Sin, Judgment, and the Human Moral Compass

The concepts of Sin and Moral Judgment stand as towering pillars in the edifice of human thought, profoundly shaping our understanding of Good and Evil, individual responsibility, and societal order. This pillar page delves into the historical evolution and philosophical underpinnings of these intertwined ideas, tracing their origins from ancient religious doctrines to their reinterpretation in secular ethics. We will explore how different traditions define transgression, the mechanisms by which moral accountability is assessed, and the enduring questions these concepts pose about human nature, free will, and the very fabric of our shared moral reality. From the divine pronouncements of Abrahamic faiths to the rigorous ethical frameworks of the Enlightenment, the journey through sin and judgment reveals the perennial human struggle to navigate the complex landscape of right and wrong.

Unpacking "Sin" – A Historical and Philosophical Overview

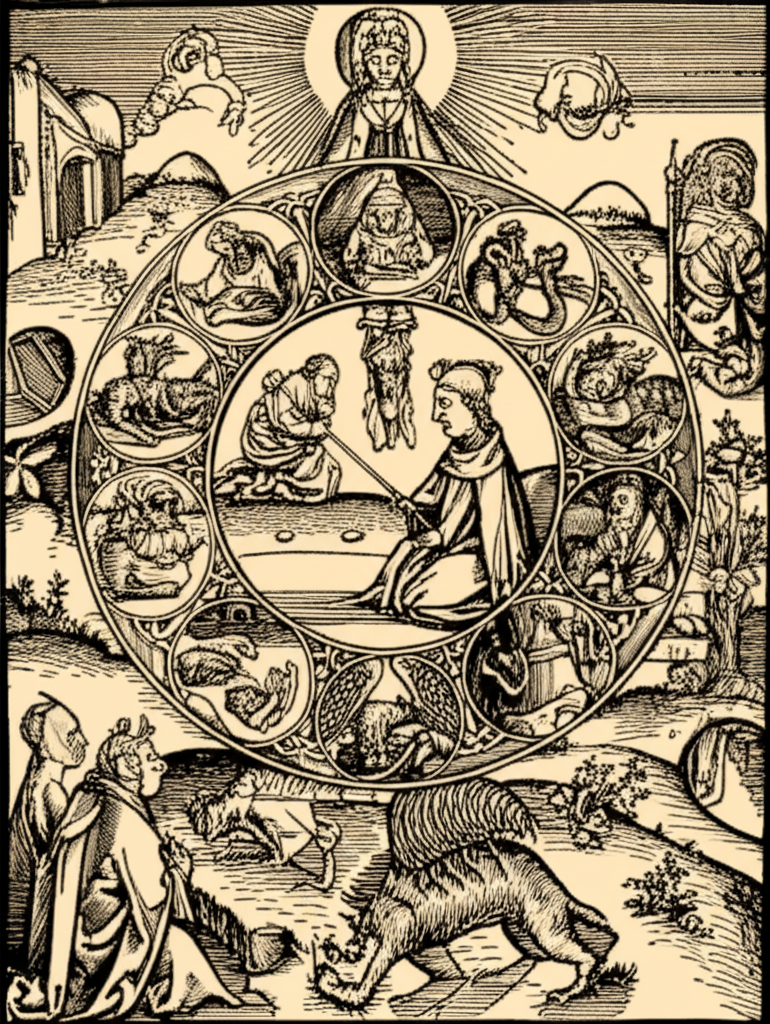

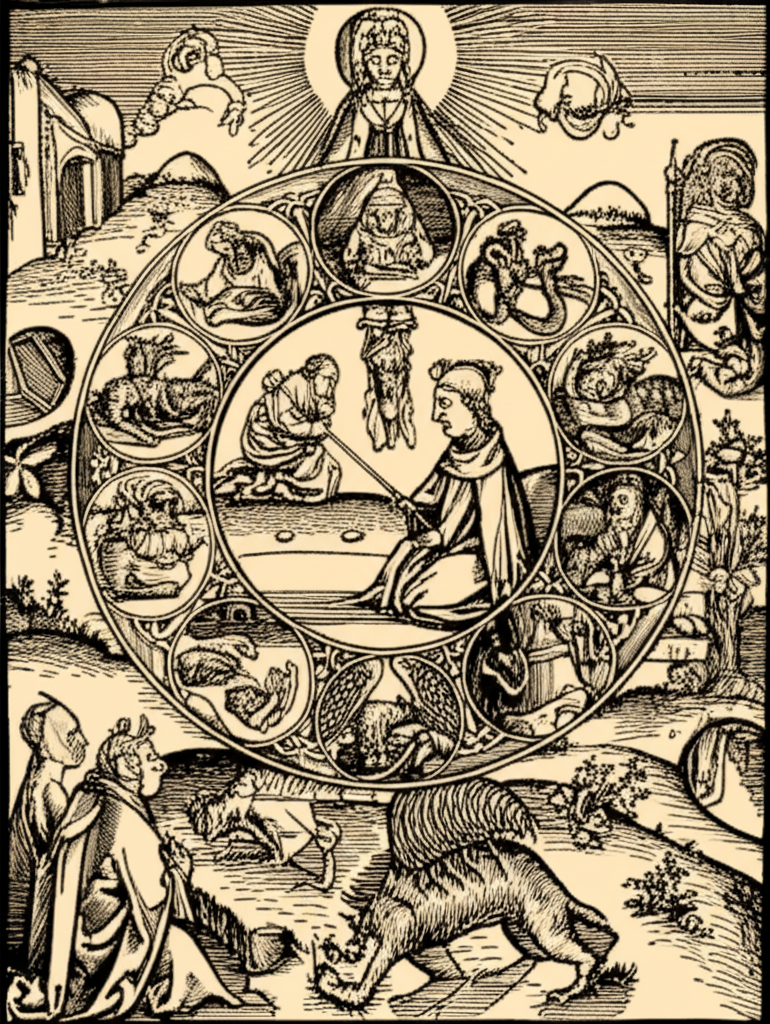

The term "sin" often evokes images rooted deeply in Religion, particularly the Abrahamic traditions, where it signifies a transgression against divine law or a separation from God. Yet, its conceptual lineage is far broader, evolving from ancient notions of ritual impurity and communal offense to profound philosophical inquiries into human nature and existential failing.

From Transgression to Existential Flaw

Historically, the understanding of Sin has undergone significant transformation:

- Ancient Roots: In early societies, wrongdoing was often viewed through the lens of taboo, ritual impurity, or actions that disrupted the cosmic or social order. The emphasis was less on individual guilt and more on collective consequence or the appeasement of deities.

- Abrahamic Traditions: Here, Sin crystallizes as an act of disobedience against God's commandments (e.g., the Ten Commandments), a failure to live up to divine expectations, or an inherent flaw (Original Sin in Christianity, as explored by St. Augustine in his Confessions). It’s a willful turning away from the Good, leading to spiritual estrangement and requiring atonement or redemption.

- Philosophical Interventions: While not always using the term "sin," philosophers like Plato in The Republic grappled with concepts of injustice and the corruption of the soul, seeing vice as a deviation from reason and the ideal form of the Good. Aristotle, in his Nicomachean Ethics, focused on moral error as a failure to achieve eudaimonia (flourishing) through virtuous action, a misstep in the pursuit of the mean.

- The Modern Shift: As societies became more secular, the notion of Sin often transmuted into "moral wrong," "ethical failing," or "harm." The focus shifted from divine displeasure to the impact on human well-being, rights, and societal cohesion.

The Architecture of Moral Judgment

If Sin defines the transgression, Judgment is the process by which that transgression is recognized, evaluated, and addressed. This process can be external (divine or societal) or internal (self-judgment), and its criteria are as varied as the moral systems that underpin them.

Who Judges? What is Judged?

- Divine Judgment: Central to many Religions, this refers to the ultimate assessment by a deity or deities of an individual's life, actions, and intentions, often determining their eternal fate. This concept, powerfully articulated in texts like the biblical Book of Revelation or Dante Alighieri's The Inferno from the Great Books of the Western World, posits an absolute moral arbiter.

- Societal Judgment: This encompasses the formal and informal ways communities evaluate behavior. Legal systems represent formal societal judgment, enforcing laws that often have roots in moral principles concerning Good and Evil. Informal judgment manifests through public opinion, social ostracization, or the bestowal of honor and shame.

- Self-Judgment (Conscience): Perhaps the most intimate form, this is the individual's internal assessment of their own actions against their personal moral code or conscience. Philosophers like Immanuel Kant, in his Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, emphasized the role of practical reason in formulating moral laws that we impose upon ourselves, leading to a sense of duty and self-accountability.

- Criteria for Judgment:

- Actions: What was done or not done?

- Intentions: Why was it done? (e.g., Kant's focus on good will).

- Consequences: What were the outcomes of the action? (e.g., Utilitarian perspectives like John Stuart Mill's Utilitarianism).

- Character: Does the action reflect a virtuous or vicious disposition? (e.g., Aristotelian ethics).

Sin and Morality – A Complex Interplay

The relationship between Sin and broader morality is intricate. While Sin is typically a religious concept, its influence on secular ethics is undeniable. Many moral prohibitions, even in non-religious contexts, echo ancient proscriptions against actions once considered sinful.

Beyond the Sacred: Secular Ethics and the Shadow of Transgression

The transition from a religiously framed understanding of wrongdoing to a secular one involves a re-evaluation of foundations:

| Feature | Religious "Sin" | Secular "Moral Wrong" |

|---|---|---|

| Source | Divine law, sacred texts, revelation | Reason, human flourishing, social contract, empathy |

| Consequence | Spiritual estrangement, divine punishment, eternal damnation | Harm to others, societal breakdown, personal guilt, legal penalty |

| Motivation | Disobedience to God, spiritual impurity | Violation of rights, injustice, suffering, irrationality |

| Remedy | Repentance, atonement, grace, forgiveness | Restitution, justice, rehabilitation, self-improvement |

Even without the concept of Sin, the human need to distinguish between Good and Evil persists. Secular ethics grapples with questions of universal moral principles, the nature of justice, and the justification for moral rules. Thinkers like Friedrich Nietzsche, in On the Genealogy of Morality, critically examined the historical development of moral concepts, suggesting that many "moral" values originated from power dynamics rather than inherent truths, challenging the very notion of absolute Good and Evil.

The Problem of Evil and the Nature of Human Agency

The existence of Sin and moral failing inevitably leads to the philosophical problem of evil: if a benevolent, omnipotent God exists, why does evil persist? This question, a cornerstone of theological and philosophical inquiry, particularly for figures like Augustine and Leibniz (in his Theodicy), deeply implicates human free will.

Free Will, Responsibility, and the Burden of Choice

- Freedom to Choose: The capacity for Sin is often seen as a direct consequence of human free will. If individuals are truly free to choose their actions, they must also be free to choose wrongly. This freedom is what imbues moral choices with significance and makes Judgment meaningful.

- Responsibility and Guilt: With freedom comes responsibility. When an individual commits a Sin or a moral wrong, they are held accountable. This accountability can manifest as external punishment or the internal experience of guilt, which can be a powerful motivator for change or a crushing psychological burden.

- Redemption and Forgiveness: The possibility of redemption, forgiveness, and moral reform is a crucial counterpoint to the concept of Sin. Whether through divine grace or human effort, the path back from transgression is a testament to the belief in human capacity for growth and the transformative power of mercy.

Contemporary Perspectives and Enduring Questions

In the 21st century, while explicit discussions of Sin may be less prevalent in mainstream discourse, the underlying concerns persist. We grapple with systemic injustices, environmental degradation, and the ethical implications of rapidly advancing technology. These contemporary challenges force us to reconsider the scope of our moral responsibility and the nature of collective Judgment.

- Collective Sin/Responsibility: Modern thought often extends moral responsibility beyond individual acts to collective actions and systemic failures. Is there such a thing as "societal sin" or "structural evil"? How do we assign Judgment in cases of historical injustice or environmental harm?

- The Evolving Moral Landscape: As our understanding of the world changes, so too do our moral frameworks. What was once considered acceptable might now be seen as deeply unethical, and vice versa. The ongoing dialogue about Good and Evil remains as vital as ever, prompting continuous reflection on our values and the principles that guide our actions.

The concepts of Sin and Moral Judgment are not relics of a bygone era but dynamic, evolving ideas that continue to shape our personal lives, our communities, and our philosophical quest to understand what it means to live a Good life.

Further Exploration:

- YouTube: "Philosophy of Sin and Evil"

- YouTube: "Moral Philosophy Explained: Kant vs. Mill"

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "The Concept of Sin and Moral Judgment philosophy"