The Concept of Sin and Moral Judgment: A Philosophical Inquiry

The concepts of sin and moral judgment lie at the very heart of human civilization, shaping our laws, our cultures, and our individual consciences. Far from being mere theological constructs, they represent humanity's enduring struggle to define Good and Evil, to understand transgression, and to establish frameworks for accountability. This pillar page will delve into the multifaceted nature of sin and judgment, exploring their historical evolution, philosophical underpinnings, and their profound impact on how we perceive ourselves and the world around us. From ancient Greek inquiries into virtue to the rigorous ethical systems of the Enlightenment and the critiques of modernity, we will navigate the complex tapestry of these fundamental ideas, drawing insights from the enduring wisdom of the Great Books of the Western World.

I. Defining Sin: More Than Just "Bad Behavior"

To speak of sin is to immediately engage with deep-seated assumptions about right and wrong, often invoking spiritual or religious frameworks. However, the concept extends beyond strictly theological definitions, touching upon universal human experiences of fault, error, and transgression.

A. Etymology and Early Understandings

The word "sin" itself, derived from Old English, originally meant "offence," "misdeed," or "injury." In its earliest forms, across various cultures, it often signified missing the mark, an archery metaphor for failing to hit the target of what is considered right or proper.

B. Sin as Transgression Against Divine Law (Religious Perspective)

Within most religious traditions, sin is fundamentally understood as an act or thought that violates divine law or goes against the will of God. This perspective is prominent in the Abrahamic religions, where Judgment is often seen as emanating from a transcendent authority.

- Judaism and Christianity: The concept of sin is central, often linked to the story of Adam and Eve's disobedience in the Garden of Eden – the "original sin" that, for many Christians, tainted humanity. Saint Augustine, in his Confessions and City of God, extensively grappled with the nature of evil and the human will, famously defining evil not as a substance, but as a privation of good.

- Islam: Sin (dhanb, khati'a, ithm) is a deviation from the path of Allah, leading to spiritual impurity and requiring repentance.

C. Sin as a Deviation from Reason or Nature (Philosophical Perspective)

Philosophers, even outside explicit religious frameworks, have explored concepts akin to sin by examining failures of reason, virtue, or natural law.

- Aristotle: In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle discusses moral error as a failure to achieve the "mean" between excess and deficiency, a deviation from virtue. While not using the term "sin," his analysis of vice as a habituated bad character aligns with the idea of a moral failing.

- Thomas Aquinas: Building on Aristotle and Augustine, Aquinas in his Summa Theologica integrated Christian theology with Aristotelian philosophy. He defined sin as "a word, deed, or desire contrary to the eternal law," linking it to both divine command and the dictates of natural reason, which reflects divine wisdom. For Aquinas, Good and Evil are intrinsically tied to human nature and its ultimate telos (purpose).

II. The Intertwined Nature of Judgment

If sin is the transgression, then judgment is the assessment and pronouncement on that transgression. This, too, manifests in various forms, from the personal to the cosmic.

A. Moral Judgment: The Human Faculty

Moral judgment refers to the human capacity to evaluate actions, intentions, character, and policies as morally good or bad, right or wrong. It is a fundamental aspect of human rationality and social interaction.

- Immanuel Kant: In his ethical works like the Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, Kant emphasized the role of reason in moral judgment, proposing the categorical imperative as a universal principle from which all duties can be derived. An action is morally right only if its maxim could be willed to become a universal law.

- David Hume: While not denying moral distinctions, Hume, in A Treatise of Human Nature, argued that moral judgment is ultimately rooted in sentiment and feeling rather than pure reason. We approve of actions that evoke pleasant sentiments and disapprove of those that cause unpleasant ones.

B. Divine Judgment: The Ultimate Arbiter

In religious contexts, divine judgment is the belief that a supreme being or beings will ultimately assess human actions and dispense justice, often in an afterlife. This belief is a powerful motivator for moral behavior within many faiths.

C. Societal Judgment: Laws, Norms, and Their Enforcement

Beyond individual and divine judgment, societies establish systems of judgment through laws, social norms, and cultural expectations. These collective judgments define what is acceptable or unacceptable behavior within a community.

Table: Types of Judgment and Their Sources

| Type of Judgment | Primary Source(s) | Scope of Authority | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moral | Individual Reason, Conscience, Empathy | Personal conduct, individual ethical decisions | Deciding whether to lie to protect someone's feelings. |

| Divine | God/Gods, Sacred Texts, Religious Doctrine | Spiritual standing, eternal consequences | Belief in an afterlife reckoning for sins committed. |

| Societal | Laws, Cultural Norms, Public Opinion, Institutions | Collective behavior, legal consequences, social standing | Legal prosecution for theft, social ostracization for breaking taboos. |

III. Historical and Philosophical Perspectives on Good and Evil

The concepts of Good and Evil are the bedrock upon which sin and judgment are constructed. Throughout history, philosophers have offered diverse and often conflicting views on their nature.

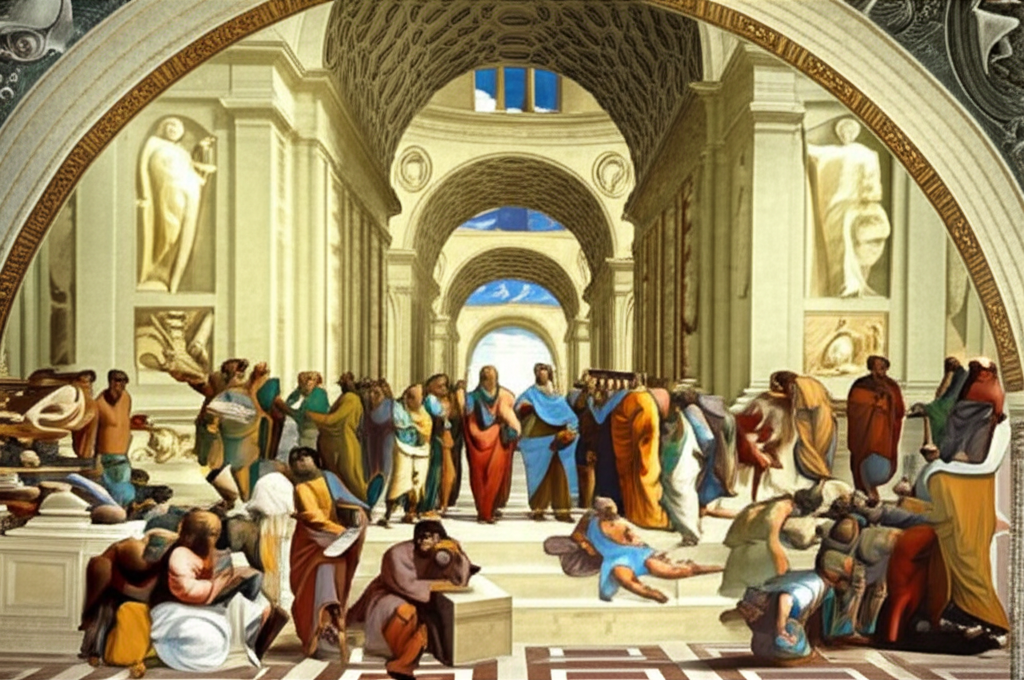

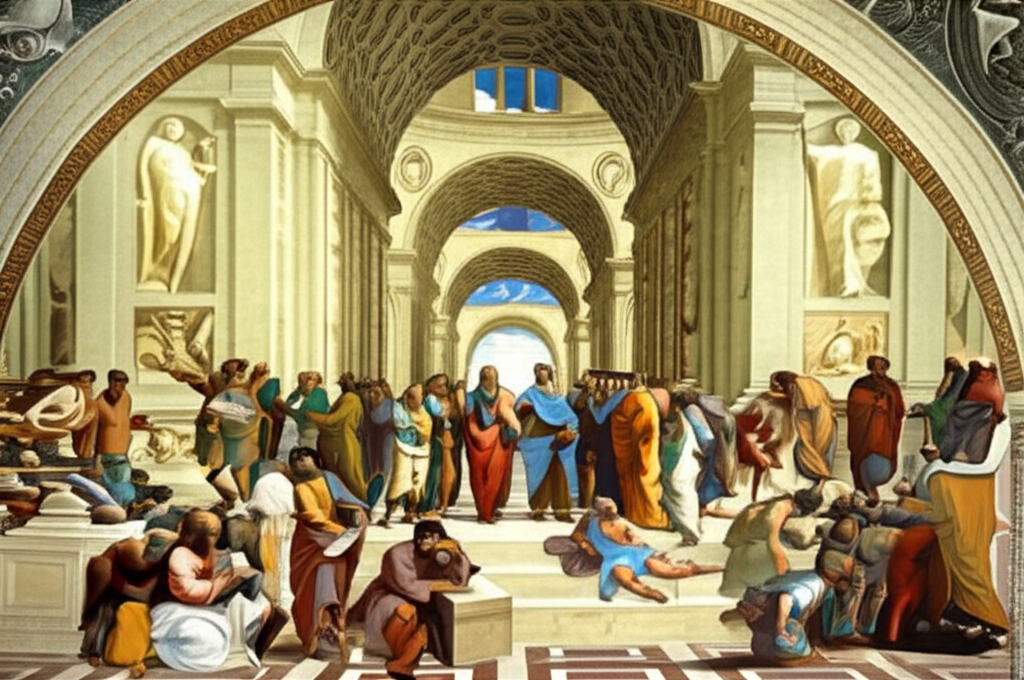

A. Ancient Greek Foundations

- Plato: For Plato, as explored in dialogues like The Republic, Good is an ultimate, transcendent Form, the Form of the Good, which illuminates all other knowledge and reality. Evil often stemmed from ignorance, a lack of understanding of the true Good. The good life, therefore, involved aligning oneself with this ultimate truth through reason.

- Aristotle: Aristotle's ethical framework is teleological, meaning it focuses on purpose or end. The ultimate Good for humans is eudaimonia (often translated as flourishing or living well), achieved through the cultivation of virtues (e.g., courage, temperance, justice) via habit and practical wisdom. Evil or vice is a failure to achieve this flourishing.

B. Judeo-Christian Theology

The Judeo-Christian tradition profoundly shaped Western understanding of Good and Evil, introducing concepts of divine command and original sin.

- The Fall and Redemption: The narrative of Adam and Eve introduces the idea of inherent human fallibility and the consequences of disobedience. The concept of God as the ultimate source of Good and the lawgiver provides a clear demarcation for sin.

- Augustine: His theological framework, influenced by Neoplatonism, saw Evil not as a positive force but as a privation or absence of Good. Sin is a turning away from God, the ultimate Good.

- Aquinas: Synthesizing faith and reason, Aquinas argued that human reason, through natural law, can discern much of Good and Evil. Sin is thus not only against God's direct command but also against the rational order inherent in creation.

C. Enlightenment and Beyond

The Enlightenment brought a shift towards reason and individual autonomy, influencing how Good and Evil were understood, often moving away from solely theological explanations.

- Immanuel Kant: Kant's ethical system is deontological, focusing on duty and moral rules. An action is Good if it is done from a sense of duty, out of respect for the moral law, and if its maxim can be universalized. Evil or immorality arises from acting on maxims that cannot be universalized or from treating others merely as means to an end.

- Friedrich Nietzsche: A radical critic of traditional morality, Nietzsche, in works like On the Genealogy of Morality, famously argued that concepts of Good and Evil (especially "good" as selflessness and "evil" as pride) were historically constructed, particularly by what he termed "slave morality" in reaction to "master morality." He called for a "revaluation of all values," questioning the inherent goodness of traditional virtues and suggesting that what was traditionally labeled sin might, in fact, be a manifestation of strength.

IV. The Psychology and Sociology of Moral Transgression

Beyond philosophical and theological definitions, understanding sin and moral failure requires examining human psychology and societal structures. Why do individuals commit acts deemed wrong, and how do societies define and respond to these transgressions?

- Intent vs. Outcome: A crucial aspect of moral judgment is the role of intent. Is an accidental harm as blameworthy as an intentional one? Philosophers like Kant emphasize the purity of the will, while consequentialists like John Stuart Mill (though not in the Great Books collection, he represents a significant counterpoint to Kantian thought) focus on outcomes.

- Conscience: The "inner voice" that guides moral decisions and produces feelings of guilt or remorse is a powerful internal mechanism related to sin and judgment. Many philosophers, from Augustine to Kant, have explored its nature and authority.

- Societal Norms and Deviance: What is considered sin or moral transgression is heavily influenced by cultural and historical context. Societal norms, laws, and educational systems play a critical role in shaping what individuals perceive as Good and Evil and how they react to Judgment.

V. Contemporary Challenges and Nuances

In the modern world, the concepts of sin and judgment continue to evolve, facing new challenges and interpretations.

- Secular Ethics vs. Religious Ethics: As societies become more pluralistic, the tension between moral frameworks rooted in Religion and those derived from secular reason (humanism, utilitarianism, contractualism) becomes more pronounced. Can a society maintain a shared sense of Good and Evil without a common religious foundation?

- Relativism vs. Universal Moral Truths: The rise of cultural relativism questions the existence of universal moral truths, suggesting that sin and judgment are entirely culturally determined. This stands in stark contrast to universalist claims, whether religious or rationalist (like Kant's).

- The Problem of Evil (Theodicy): For religious frameworks, the existence of suffering and evil in a world supposedly created by an omnipotent, omnibenevolent God remains a profound philosophical challenge, leading to ongoing theological and philosophical debates.

VI. Conclusion: Navigating the Moral Labyrinth

The journey through the concepts of sin and moral judgment reveals not only the enduring concerns of humanity but also the remarkable diversity of thought dedicated to understanding Good and Evil. From the divine pronouncements of ancient faiths to the rigorous logical deductions of philosophers, the quest to define transgression and establish frameworks for accountability remains central to the human condition. Whether viewed as an offense against God, a failure of reason, or a deviation from societal norms, sin prompts judgment, forcing individuals and communities to constantly re-evaluate their values, their actions, and their very purpose. As we continue to grapple with complex ethical dilemmas, the insights gleaned from these timeless philosophical inquiries remain an indispensable guide in navigating the intricate moral labyrinth of our existence.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Plato's Allegory of the Cave moral implications"

-

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Kantian ethics categorical imperative explained"