The Ever-Shifting Sands of Morality: Deconstructing Good and Evil

The concepts of Good and Evil form the very bedrock of human civilization, shaping our laws, our cultures, and our personal consciences. Yet, defining them objectively has been one of philosophy's most enduring and perplexing challenges. This article delves into how various moral systems, drawing heavily from the Western philosophical tradition, have grappled with these fundamental ideas, exploring the roles of Duty, Sin, and the cultivation of Virtue and Vice in our understanding of what it means to live a moral life. From ancient Greek ideals of flourishing to theological imperatives and Enlightenment reason, we’ll trace the evolution of these concepts, revealing their profound impact on our ethical landscape.

The Enduring Question: What is Good? What is Evil?

Across millennia and myriad cultures, humanity has sought to delineate the acceptable from the abhorrent, the praiseworthy from the blameworthy. This universal impulse to categorize actions and intentions as Good and Evil speaks to a deep-seated need for order and meaning. However, the exact nature of these categories remains a subject of intense debate. Is "good" an intrinsic quality, a divine command, a societal construct, or a path to personal fulfillment? And conversely, does "evil" represent a deviation from a natural order, a transgression against God, or simply an act that causes harm? The answers, as we shall see, are as diverse as the minds that have pondered them.

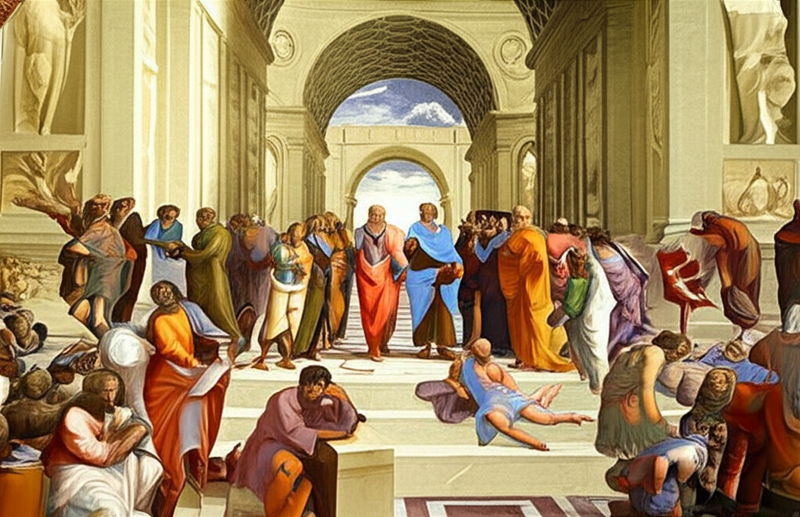

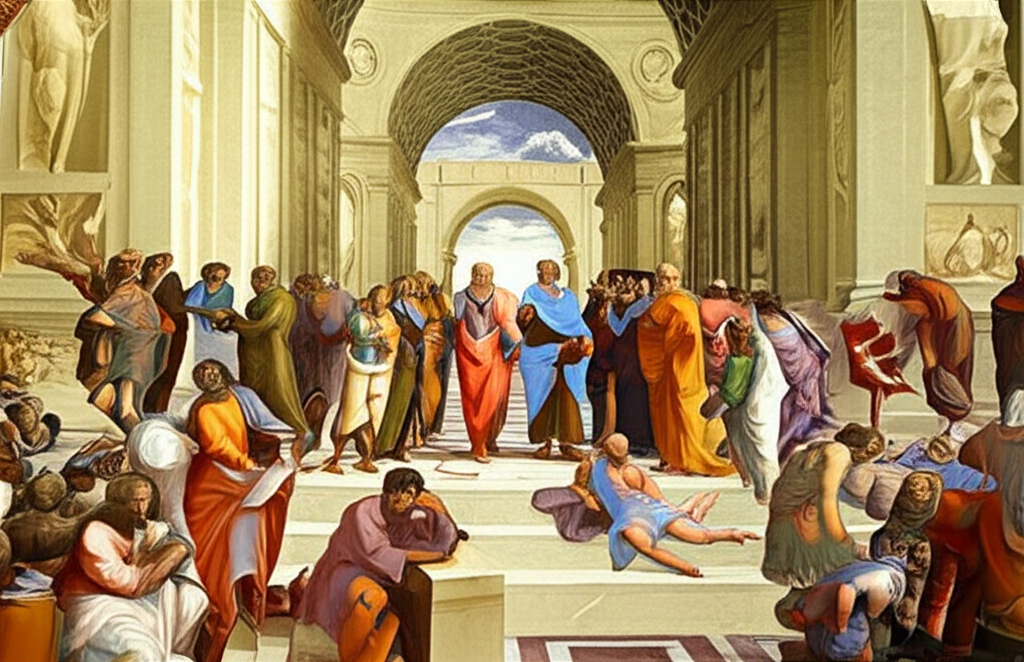

Ancient Foundations: Virtue, Character, and the Good Life

For the ancient Greeks, particularly Plato and Aristotle, the notion of Good was inextricably linked to human flourishing and the development of character.

- Plato's Ideal of the Good: In Plato's philosophy, Good is not merely an attribute but an ultimate Form, the highest reality, illuminating all other Forms and making knowledge possible. To live a good life was to align oneself with this ultimate Good, striving for wisdom and justice. Evil, in this view, often stemmed from ignorance or a lack of understanding of the true Good.

- Aristotle and Eudaimonia: Aristotle, ever the pragmatist, focused on eudaimonia – often translated as flourishing or living well – as the ultimate aim of human life. For him, Virtue and Vice were central. Virtues were character traits, cultivated through habit and reason, that enabled an individual to achieve eudaimonia.

- Virtues like courage, temperance, justice, and wisdom represented a "golden mean" between two extremes of vice (e.g., courage is the mean between cowardice and recklessness).

- Vices, therefore, were deficiencies or excesses of these character traits that hindered one's ability to live a fulfilling, rational life.

- The "good" action was one performed by a virtuous person acting from a virtuous character.

This emphasis on character and the cultivation of virtue laid a foundational understanding of what it means to be a moral agent, where the internal state of the individual was paramount.

Divine Commands and Moral Imperatives: The Role of Duty and Sin

With the rise of monotheistic religions, particularly Christianity, the understanding of Good and Evil took on a new dimension, rooted in divine will and the concept of Duty.

-

Augustine and Aquinas: Theological Ethics:

- For thinkers like Augustine and Aquinas, Good was ultimately defined by God's nature and commands. Evil was understood primarily as Sin – a transgression against God's law, a turning away from the divine Good.

- Augustine famously grappled with the problem of evil, suggesting it was not a substance but a privation of good. Original Sin further complicated human morality, positing an inherent inclination towards evil that required divine grace to overcome.

- Aquinas, integrating Aristotelian thought with Christian theology, developed Natural Law theory, arguing that God's eternal law is knowable through human reason. Our Duty to God and to our fellow humans is derived from understanding this natural law, which guides us towards the good and away from evil.

-

Kant's Deontological Ethics: Duty for Duty's Sake:

Immanuel Kant, a towering figure of the Enlightenment, sought to ground morality in pure reason, independent of theological dictates or outcomes. For Kant, the Good resides in the Good Will – the intention to act out of Duty alone, rather than inclination or consequence.- Categorical Imperative: Kant's ethical framework is built upon the Categorical Imperative, a universal moral law that dictates how one should act. It has several formulations, including:

- Universalizability: Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law. If an action cannot be universalized without contradiction, it is morally wrong (Evil).

- Humanity as an End: Treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, always at the same time as an end, never merely as a means.

- Thus, for Kant, an action is Good if it is performed purely out of Duty to the moral law, regardless of the outcome. An action is Evil if it violates this moral law, treating others as mere means, or if its underlying maxim cannot be rationally universalized.

- Categorical Imperative: Kant's ethical framework is built upon the Categorical Imperative, a universal moral law that dictates how one should act. It has several formulations, including:

Contrasting Ethical Frameworks: A Snapshot

| Ethical Framework | Primary Definition of "Good" | Primary Definition of "Evil" | Motivator for Moral Action | Key Philosophers (Great Books) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virtue Ethics | Living a flourishing life (Eudaimonia) through character traits. | Failure to achieve flourishing; acting from vice. | Cultivation of Virtue. | Plato, Aristotle |

| Divine Command Theory | Adherence to God's will and divine law. | Sin (transgression against God's commands). | Duty to God; hope of salvation. | Augustine, Aquinas |

| Deontology (Kant) | Acting from a Good Will in accordance with moral Duty. | Acting against the Categorical Imperative; treating others as means. | Duty for duty's sake; reason. | Immanuel Kant |

The Relativist Challenge and Beyond

While these philosophical titans sought universal truths, the modern era has seen increasing challenges to objective definitions of Good and Evil. Cultural relativism suggests that moral norms are products of specific societies, making universal judgments problematic. Friedrich Nietzsche, a provocative figure often found in the Great Books, famously titled one of his works Beyond Good and Evil, arguing for a "revaluation of all values." He critiqued traditional morality, particularly Christian ethics, as a "slave morality" that repressed human potential, advocating for individuals to create their own values and embrace a "will to power." This perspective pushes us to question the very foundations of our moral systems, highlighting how definitions of Good and Evil can be culturally constructed and historically contingent.

Synthesizing the Threads: Modern Perspectives

Today, the debate over Good and Evil continues to evolve. Contemporary ethicists often draw from, and synthesize, these historical frameworks. We grapple with utilitarian calculations (the greatest good for the greatest number), rights-based ethics, and the complexities of applied ethics in a globalized world. Yet, the core questions remain:

- Are Good and Evil objective realities or subjective constructs?

- How do we balance individual autonomy with collective well-being?

- What is our Duty to ourselves, to others, and to the planet?

Understanding the historical philosophical journey through Virtue and Vice, Duty, and the concept of Sin provides an invaluable framework for navigating these contemporary dilemmas. It reminds us that while the answers may be elusive, the pursuit of understanding Good and Evil is an inherently human and necessary endeavor, shaping not just our individual lives but the very fabric of our shared existence.

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Introduction to Ethics: Virtue Ethics vs. Deontology""

📹 Related Video: KANT ON: What is Enlightenment?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""What is Good and Evil? Exploring Philosophical Concepts""