The Unfolding Tapestry: Navigating the Citizen's Relationship to the State

Summary:

Our journey through political philosophy invariably leads us to the intricate, often tumultuous, relationship between the Citizen and the State. This article delves into the historical foundations of this bond, drawing from the Great Books of the Western World to explore concepts of Law, Duty, and the evolving understanding of governance. From ancient Greek ideals of civic participation to Enlightenment theories of social contract, we examine how thinkers have grappled with the rights and responsibilities that bind individuals to their governing structures, and why this dialogue remains perpetually relevant.

Introduction: The Enduring Question of Belonging

Grace Ellis here, inviting you to ponder a question as old as organized society itself: What truly defines the connection between an individual and the collective entity that governs? It's a relationship fraught with both profound responsibility and inherent tension, a dance between individual liberty and collective order. To truly grasp its complexities, we must turn to the venerable voices that have shaped our understanding of the Citizen and the State, exploring how Law mediates their interactions and what Duty compels each to uphold.

Foundations from the Great Books: A Historical Lens

The philosophical bedrock of the citizen-state relationship is deep and varied, reflecting the diverse political landscapes from which these ideas emerged. The Great Books of the Western World offer an unparalleled exploration of this fundamental dynamic.

-

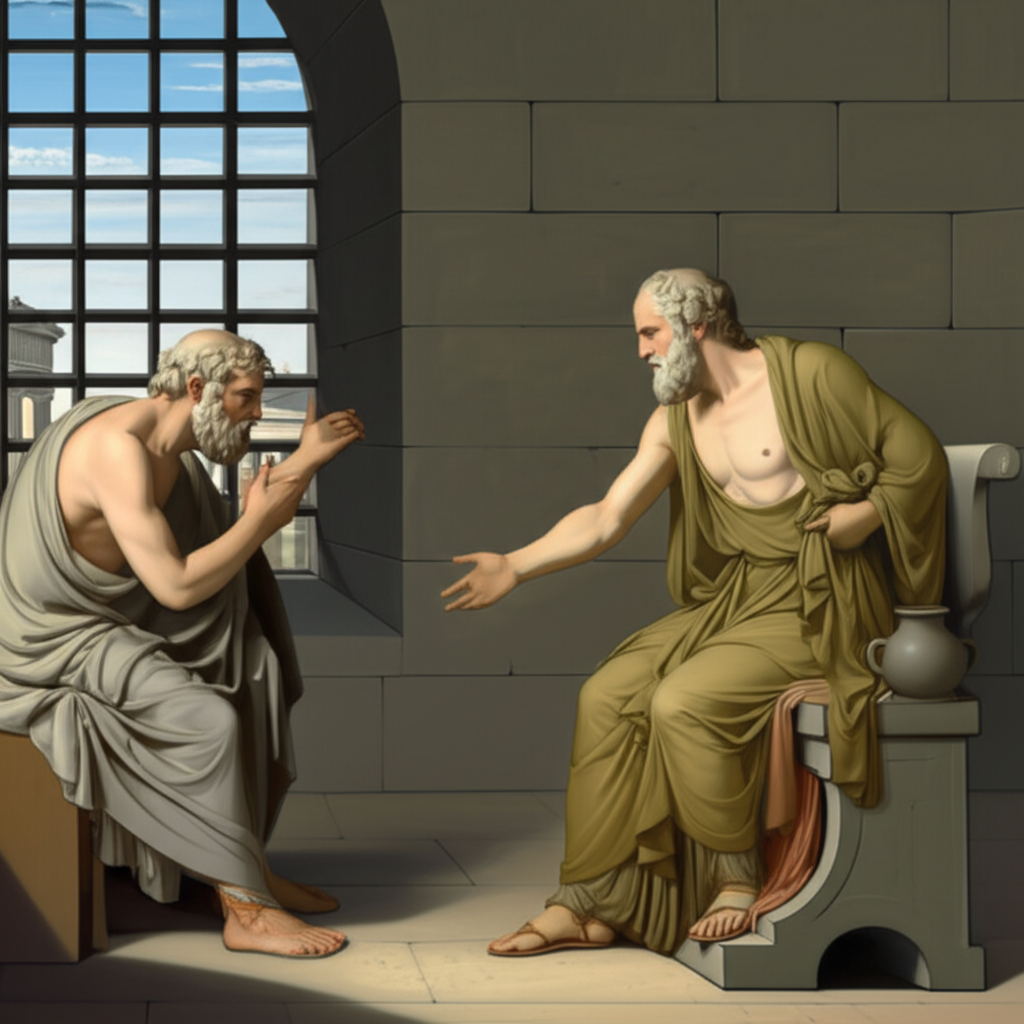

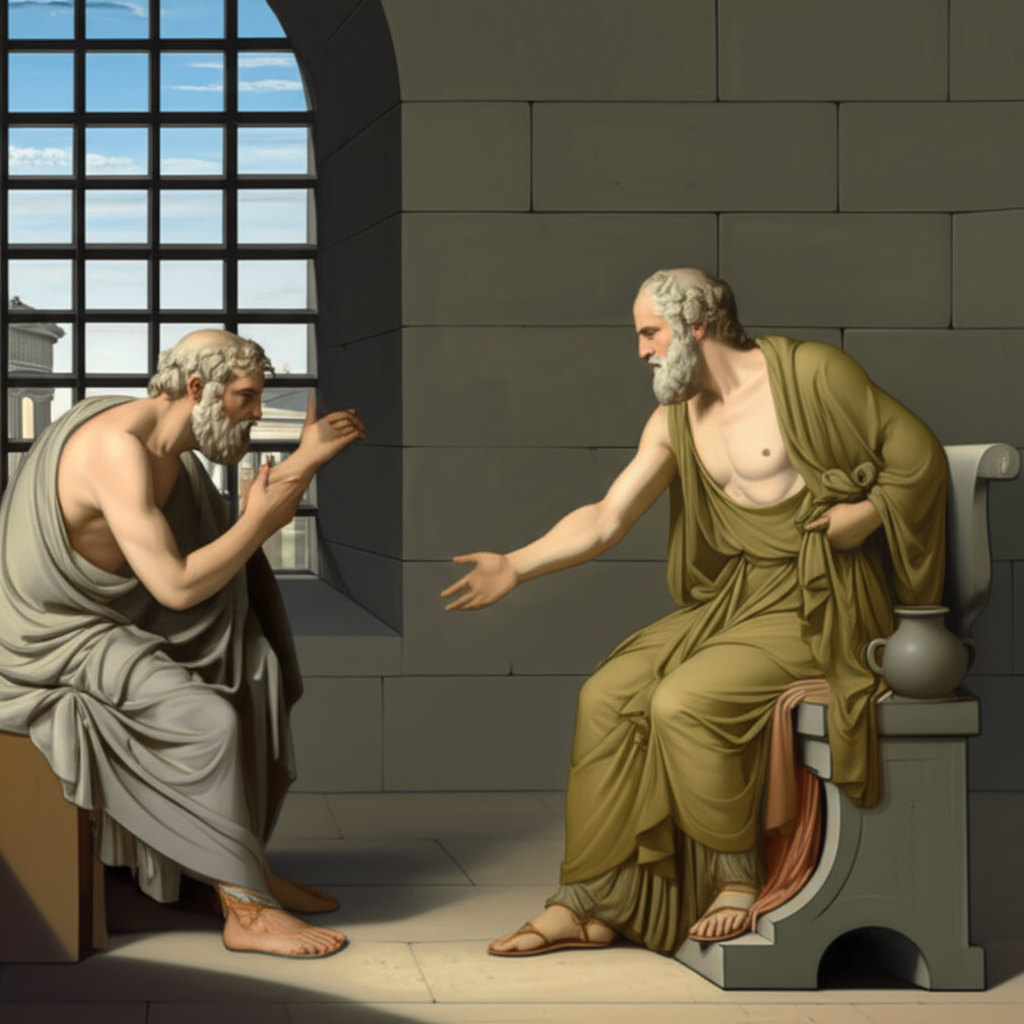

Plato and the Ideal Polis:

In ancient Greece, particularly within Plato's Republic, the citizen's role is intrinsically linked to the pursuit of justice within the State. For Plato, the ideal State is a harmonious organism where each part (including the citizen) performs its designated duty. His dialogue Crito powerfully illustrates the dilemma of individual conscience versus the Law of the State, as Socrates chooses to accept his sentence rather than defy Athenian law, arguing that having lived under and benefited from the city's laws, he implicitly agreed to abide by them, even unto death. This highlights a profound sense of civic duty and obligation. -

Aristotle and the Political Animal:

Aristotle, in his Politics, views man as a "political animal" (zoon politikon), inherently designed to live in a polis (city-state). For him, citizenship isn't merely residence but active participation in the affairs of the State – in deliberating, judging, and holding office. The State exists not just for life, but for the "good life," and the citizen's duty is to contribute to this flourishing, guided by Law that aims at the common good. -

Hobbes and the Social Contract Born of Fear:

Moving into the Enlightenment, Thomas Hobbes's Leviathan presents a stark vision. In his view, the "state of nature" is a "war of all against all." To escape this brutal existence, individuals enter into a social contract, surrendering some of their absolute freedom to a sovereign State in exchange for security and order. The citizen's duty here is primarily obedience to the Law established by the sovereign, as defiance risks a return to chaos. The power of the State is absolute, necessary to maintain peace. -

Locke and Rights-Based Governance:

John Locke, in his Two Treatises of Government, offers a more optimistic, yet equally foundational, perspective. He posits natural rights—life, liberty, and property—that pre-exist the State. The State is formed through a social contract to protect these rights, with its authority derived from the consent of the governed. Here, the citizen's duty is to obey just Law, but also possesses the right, and perhaps even the duty, to resist tyranny when the State oversteps its legitimate bounds and infringes upon natural rights. -

Rousseau and the General Will:

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in The Social Contract, introduces the concept of the "general will." For Rousseau, true liberty is found not in individual caprice, but in obedience to laws that citizens collectively impose upon themselves for the common good. The citizen is both subject and sovereign, participating in the creation of the Law to which they are bound. The State is an expression of this general will, and the citizen's duty is to actively engage in shaping it.

Key Concepts in Focus

To truly understand this relationship, we must dissect its core components:

- The Citizen: More than just an inhabitant, a citizen is an individual endowed with specific rights and responsibilities within a State. This status often implies legal recognition, political participation, and a reciprocal relationship of protection and obligation.

- The State: This refers to the organized political community under one government. It encompasses institutions, laws, and the apparatus of governance that exercises authority over a defined territory and its population.

- Law: The system of rules that a particular country or community recognizes as regulating the actions of its members and which it may enforce by the imposition of penalties. Law is the primary mechanism through which the State interacts with its citizens.

- Duty: A moral or legal obligation; a responsibility. For the citizen, duty often includes obeying laws, paying taxes, and participating in civic life. For the State, duty can involve protecting its citizens, upholding justice, and ensuring the common welfare.

The Dynamic Tension: Rights and Responsibilities

The relationship between the Citizen and the State is rarely static or perfectly harmonious. It's a dynamic interplay marked by:

| Aspect | Citizen's Perspective | State's Perspective |

|---|---|---|

| Rights | Demand protection of fundamental liberties | Obligation to secure and uphold individual rights |

| Duties | Obligation to obey laws, pay taxes, participate | Expectation of civic responsibility and compliance |

| Power | Exercise of voice, vote, and potential resistance | Authority to legislate, enforce, and govern |

| Legitimacy | Derived from consent, justice, and effective governance | Maintained through adherence to established laws and principles |

This tension is precisely where philosophical inquiry thrives. When does a citizen's duty to the State become oppressive? When does the State's power infringe upon the citizen's fundamental rights? These are not easily answered questions, and they form the perennial debate at the heart of political philosophy.

Contemporary Echoes and Enduring Relevance

Even in our modern, globally interconnected world, the foundational questions posed by the Great Books remain acutely relevant. Debates over surveillance, civil disobedience, taxation, voting rights, and the role of government in individual lives are all contemporary manifestations of the age-old dialogue between the Citizen and the State.

Understanding these historical perspectives provides us with a critical framework to analyze current events and participate more thoughtfully in our own political communities. It reminds us that the balance between individual freedom and collective order is a delicate, ongoing negotiation, shaped by our understanding of Law, Duty, and the very nature of human society.

**## 📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Social Contract Theory Explained" and "Plato Crito Summary""**

In essence, the relationship between the Citizen and the State is a continuous philosophical project. It demands our attention, our critical engagement, and our willingness to delve into the wisdom of those who came before us, to better navigate the complexities of our shared political existence.