The Noble Pursuit: Unpacking the Aristocratic Idea of the Good Life

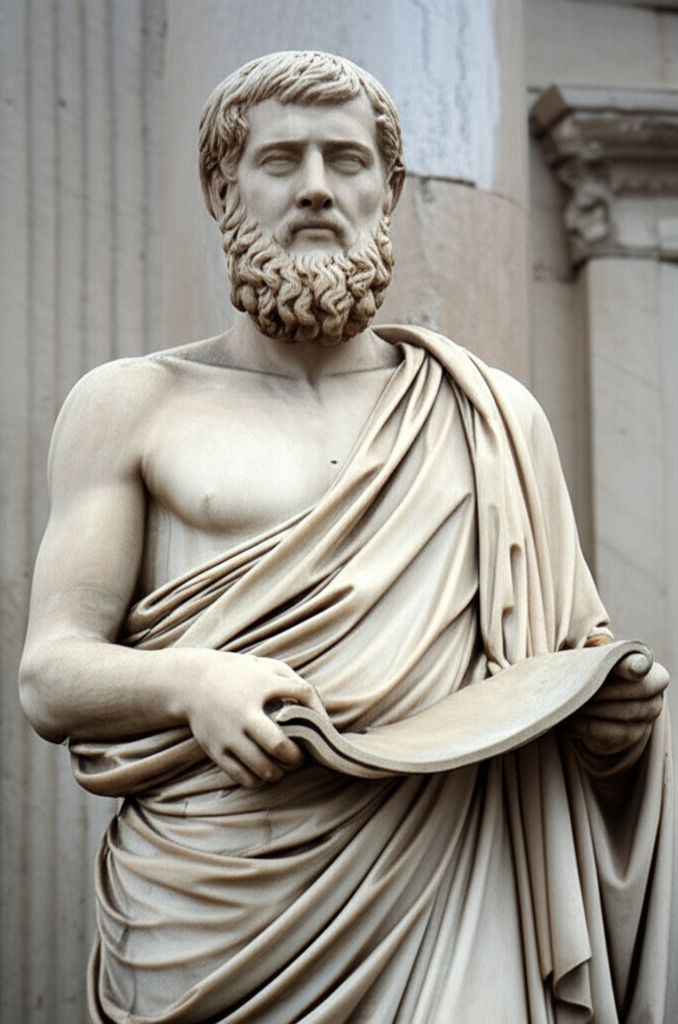

The Aristocratic Idea of the Good Life, as explored within the rich tapestry of the Great Books of the Western World, is far more nuanced than a simple birthright or social standing. It is, at its core, a philosophical framework centered on the cultivation of excellence (arête), virtue, and the pursuit of a profound and enduring form of happiness known as eudaimonia. This isn't merely about pleasure or comfort, but about flourishing as a human being through rational activity and moral integrity. For the ancient thinkers like Plato and Aristotle, the "aristocrat" was not just someone born into privilege, but rather the individual who truly embodied and strived for the best way to live, demonstrating a superior understanding of Good and Evil and a commitment to moral rectitude.

Defining the Aristocratic Ideal: Beyond Lineage

When we speak of Aristocracy in this philosophical context, we're not primarily referring to a system of government or a social class determined by inherited wealth or title. Instead, we delve into the etymological root: aristoi, meaning "the best." The Aristocratic Idea of the Good Life posits that there is an objectively "best" way for humans to live, and that the "good" individual is one who strives to embody this ideal.

- Rule of the Best: In Plato's Republic, the ideal state is governed by "philosopher-kings," individuals whose wisdom and virtue make them uniquely qualified to lead. Their "good life" is intertwined with the good of the polis.

- Excellence as a Goal: Aristotle, in his Nicomachean Ethics, emphasizes arête – excellence or virtue – as the central component of a good life. This excellence applies to all aspects of human endeavor, from craft to character.

This foundational understanding shifts the focus from external circumstances to internal cultivation, framing the good life as an achievement rather than an endowment.

The Pursuit of Eudaimonia: Happiness as Flourishing

At the heart of the aristocratic ideal lies the concept of eudaimonia, often translated as happiness or "flourishing." This is not the fleeting pleasure of sensory gratification, but a state of being that results from living a life of virtue and rational activity.

- Eudaimonia vs. Hedonism: Unlike hedonism, which prioritizes pleasure, eudaimonia is a deeper, more stable state achieved through moral action and the full actualization of one's human potential. It encompasses well-being, living well, and doing well.

- Rational Activity: For Aristotle, human beings are distinguished by their capacity for reason. Therefore, the highest form of eudaimonia is found in living a life guided by reason, engaging in contemplation, and exercising intellectual virtues.

This pursuit of flourishing requires a constant effort to discern and act upon what is truly good, a task that demands intellectual rigor and moral courage.

Virtues of the Aristocratic Soul: Navigating Good and Evil

The aristocratic ideal provides a clear framework for distinguishing Good and Evil through the cultivation of specific virtues. These aren't merely abstract concepts but practical dispositions that guide behavior and shape character.

| Virtue | Description | Philosophical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Sophrosyne | Temperance, self-control, moderation. | The ability to master one's appetites and desires, maintaining balance and avoiding excess. |

| Courage | Bravery in the face of fear, moral fortitude. | Essential for upholding justice and acting virtuously even when it is difficult or dangerous. |

| Justice | Fairness, righteousness, giving each their due. | A cardinal virtue that governs relationships with others and ensures societal harmony. |

| Wisdom | Practical wisdom (phronesis) and theoretical wisdom (sophia). | The ability to discern the appropriate means to a good end, and the understanding of fundamental truths. |

| Magnanimity | Greatness of soul, proper pride, deserving of great honors. | Unique to the aristocratic ideal, it signifies a noble spirit that values honor and acts with a sense of self-respect. |

These virtues are not isolated traits but interconnected aspects of a unified character. The truly "good" person integrates these virtues into a harmonious whole, making virtuous action a natural outflow of their being.

The Challenge and Enduring Relevance of the Idea

While the term "aristocracy" might conjure images of outdated social hierarchies, the philosophical Idea of the "best" life, lived through excellence and virtue, remains profoundly relevant. Critics might argue that such an ideal is elitist or unattainable for the majority. However, its enduring power lies in its challenge to each individual to strive for their highest potential, regardless of their starting point.

The aristocratic ideal compels us to ask:

- What does it mean to live a truly good life, beyond mere survival or comfort?

- How do we cultivate the virtues necessary to achieve genuine happiness?

- What is our responsibility in discerning and pursuing Good and Evil in a complex world?

The Aristocratic Idea of the Good Life, therefore, is not a relic of the past but a timeless invitation to engage in the rigorous and rewarding journey of self-improvement and moral excellence, a journey that ultimately defines human flourishing.

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Aristotle Eudaimonia Explained""

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Republic Philosopher Kings""