From the Archives of Ancient Greece: Sugrue’s commentary on Plato’s mistrust of poets. Insights from the Dialogues: The poet’s role in society (Republic, 595a-608b). Chance and Fate: The symbolic role of art and poetry in ancient games.

Dr. Michael Sugrue provides a profound analysis of Plato’s mistrust of poets in The Republic, focusing particularly on Book X. Sugrue emphasizes that Plato’s critique is not an outright condemnation of art but a caution against its potential to mislead. For Plato, poets and artists create imitations that appeal to the emotions, bypassing rational judgment. This is evident in Plato’s claim that poets are imitators of appearances rather than creators of truth. Dr. Sugrue articulates Plato’s concern that poetry stirs emotions, leading individuals away from the rational path towards virtue and the Good.

Sugrue further explains how Plato’s critique is rooted in the distinction between the three parts of the soul: the rational, the spirited, and the appetitive. Poetry, for Plato, engages primarily with the appetitive and spirited parts of the soul, which are prone to desire and emotional excitement. This becomes problematic when such engagement leads people away from rational deliberation. Sugrue suggests that this tension between philosophy and poetry is not about rejecting the arts entirely, but about questioning their purpose and influence on society’s moral framework.

A relevant modern example can be drawn from the proliferation of social media and the arts today. How often do we encounter narratives, videos, or even memes that appeal directly to our emotions rather than to our reason? Plato’s warning about the persuasive power of poetry extends to our contemporary media landscape, where emotional appeals often overshadow reasoned discourse. This concern makes Plato’s critique as relevant as ever.

Insights from the Dialogues: Quoting Plato

In Republic, Book X (595a-608b), Plato argues that poets are like painters who create images that resemble reality but are not true reality. He famously describes poetry as “a shadow of a shadow,” distancing it from the realm of truth. Plato’s metaphor of the bed—the one made by the carpenter, the one painted by the artist, and the one created by the divine—illustrates his idea of imitative art. The divine bed represents the Form of the bed, the carpenter’s bed is its practical manifestation, and the artist’s painting is merely a superficial imitation of the carpenter’s work. This hierarchy reveals Plato’s distrust of art’s capacity to convey truth.

Plato’s critique culminates in the famous expulsion of poets from his ideal city. He argues that poets, by appealing to the irrational parts of the soul, can lead citizens astray. The Republic makes it clear that Plato’s ideal society is one where the arts are subjected to rational oversight to ensure that they contribute to the cultivation of virtue. This raises a provocative question: If art is not aligned with moral truth, does it have a place in society?

Such a notion may seem extreme, but consider the influence of popular media on collective perceptions today. When powerful narratives shape our understanding of reality, Plato’s critique becomes an invitation to critically assess the stories we embrace. The question isn’t whether art should exist, but how it should align with the values and virtues we seek to cultivate in our lives.

Chance and Fate: Exploring Ancient Games

Art and poetry in ancient cultures were intertwined with symbolic games and rituals, reflecting broader narratives of fate, fortune, and human agency. The Greeks played games of chance, such as knucklebones (astragali), not only as entertainment but as metaphors for life’s uncertainties. In this way, the outcomes of these games were seen as reflections of divine will or fate, closely paralleling the role of art in reflecting and influencing the human experience.

Much like these games, art and poetry could be seen as symbolic reflections of life’s unpredictability. When poets crafted their verses, they played a game with fate and human emotions, shaping perceptions and guiding actions in subtle yet profound ways. Just as in knucklebones, where the players’ skill and fate intertwine, art presents a duality of craftsmanship and unforeseen impact. Plato recognized this duality and sought to ensure that art’s influence on society would lean toward enlightenment rather than emotional manipulation.

Explore the Mystical World of Astraguli: Ancient Games of Chance with Cultural Significance.

This raises an interesting connection: What if our modern games—whether board games, video games, or social dynamics—function similarly to art in their capacity to shape perceptions? In ancient Greece, rituals surrounding games and art were opportunities for reflection on luck, skill, and the human condition. Plato’s critique invites us to consider what narratives our games and art are telling today and whether they align with our aspirations for the good life.

Virtues Revisited: Practical Lessons for Today

This week, let’s explore the virtue of prudence, or phronesis. In the context of Plato’s critique, prudence involves the careful discernment of truth amidst the allure of imitation. Plato urges us to develop an awareness of how art and narratives shape our beliefs and values. It’s not about rejecting artistic expression but approaching it with a critical eye. Plato’s idea of prudence challenges us to be mindful of the media we consume and the emotions they evoke.

In a world flooded with visual and emotional stimuli, prudence calls for a balance between emotional engagement and rational deliberation. For example, while a powerful film or song might stir deep feelings, Plato would encourage us to reflect on the underlying message and its alignment with our values. He might ask, “Does this piece of art move you towards the Good, or does it appeal to desires that could lead you astray?”

At planksip.org, this concept of prudence is essential to our community’s exploration of ancient wisdom. By encouraging critical engagement with art and narratives, we strive to embody the ideal of Plato—a philosopher devoted to the pursuit of truth and the cultivation of the soul.

Engage with Us: Reader’s Corner

This week, we invite you to reflect on Plato’s critique of poets and artists. Do you think art should be held to a moral standard, or does such a constraint limit creative expression? Are there parallels between Plato’s critique and the way we engage with modern media today? Join the conversation on planksip.org, where we reimagine Plato as an ideal worth striving for. Share your reflections with us, and we may feature your insights in an upcoming issue!

Closing Reflection: Socrates’ Enduring Legacy

Plato’s critique of poets, though seemingly harsh, stems from a deep concern for the soul’s alignment with truth and virtue. In questioning the role of art, he follows Socrates’ legacy of challenging accepted norms and encouraging thoughtful self-examination. Just as Socrates urges us to examine our lives, Plato urges us to examine the stories and narratives we accept as truth.

In this way, Plato’s critique becomes not just a rejection of art, but an invitation to engage more deeply with the world around us. By questioning the narratives that shape our beliefs, we can cultivate a more thoughtful and deliberate approach to the pursuit of the Good. Let’s continue this legacy of thoughtful examination together.

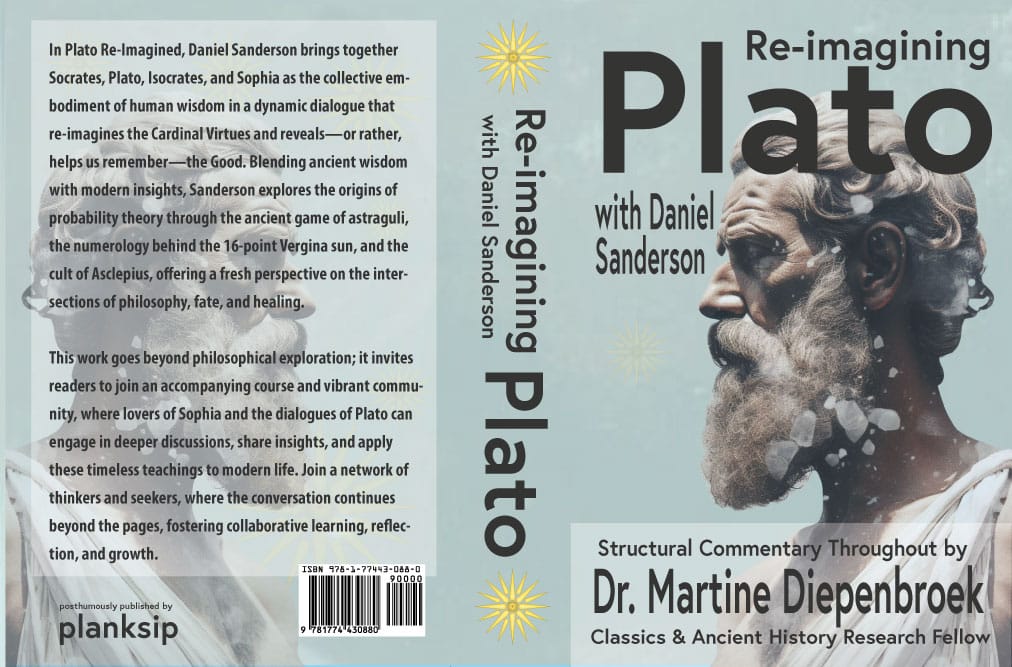

Plato Re-Imagined

This course offers 32 comprehensive lectures exploring most of Plato's dialogues. These lectures guide students toward a consilient understanding of the divine—a concept that harmonizes knowledge across disciplines and resonates with secular and religious leaders. As a bonus, Lecture #33 focuses on consilience, demonstrating how different fields of knowledge can converge to form a unified understanding.