Defining the One and the Many: A Core Metaphysical Inquiry

The question of the One and Many stands as a foundational pillar of philosophical inquiry, a persistent enigma that has occupied the greatest minds throughout history. At its heart, this problem asks: How can we reconcile the apparent unity of existence with its undeniable diversity? Is reality fundamentally a single, unified whole, or is it an aggregate of distinct, individual entities? This article delves into the historical and conceptual Definition of this profound Metaphysics problem, exploring the various ways philosophers have grappled with the Relation between unity and multiplicity, drawing extensively from the rich tapestry of the Great Books of the Western World. We shall navigate the intellectual currents that sought to understand how singular identities can partake in universal concepts, and how the vast array of particulars can somehow cohere into a meaningful cosmos.

I. The Enduring Enigma: What is the One and the Many?

The problem of the One and Many is perhaps the central question of Metaphysics, concerning the ultimate nature of reality. It is the quest to understand how the world, which presents itself to us as a bewildering array of distinct objects, events, and qualities (the Many), can also be conceived as a coherent, unified system (the One). This isn't merely an abstract puzzle; it touches upon our very understanding of identity, change, knowledge, and the very fabric of existence.

Consider a single human being: they are one person, yet composed of countless cells, thoughts, experiences, and roles (the Many). Or consider the concept of "justice": it is a singular idea (the One), but manifested in an infinite variety of specific actions, laws, and situations (the Many). How do these poles—unity and multiplicity—interact? What is the Relation that binds them, or separates them? This fundamental tension has driven philosophical discourse for millennia.

II. Ancient Echoes: From Parmenides to Plato

The earliest Western philosophers confronted the One and Many with remarkable directness, laying the groundwork for all subsequent thought.

A. Parmenides and the Unchanging One

Parmenides of Elea, a pre-Socratic thinker, famously argued for the absolute unity and immutability of being. For Parmenides, what is, is; what is not, is not. Change, motion, and multiplicity were mere illusions, products of unreliable sensory perception. True reality, accessible only through reason, was a single, indivisible, unchanging, and eternal One. The Many, in its fragmented and transient form, was fundamentally unreal. This radical monism presented a stark challenge: if only the One exists, how can we account for the apparent diversity we experience?

B. Heraclitus and the Flux of Many

In stark contrast, Heraclitus of Ephesus championed the primacy of change and multiplicity. His famous dictum, "You cannot step into the same river twice," underscored his belief that everything is in a constant state of flux. For Heraclitus, strife and opposition were the very essence of existence, giving rise to the dynamic interplay of the Many. While he posited a unifying Logos (reason or law) that governed this change, his emphasis was firmly on the ceaseless becoming, where stability was an illusion.

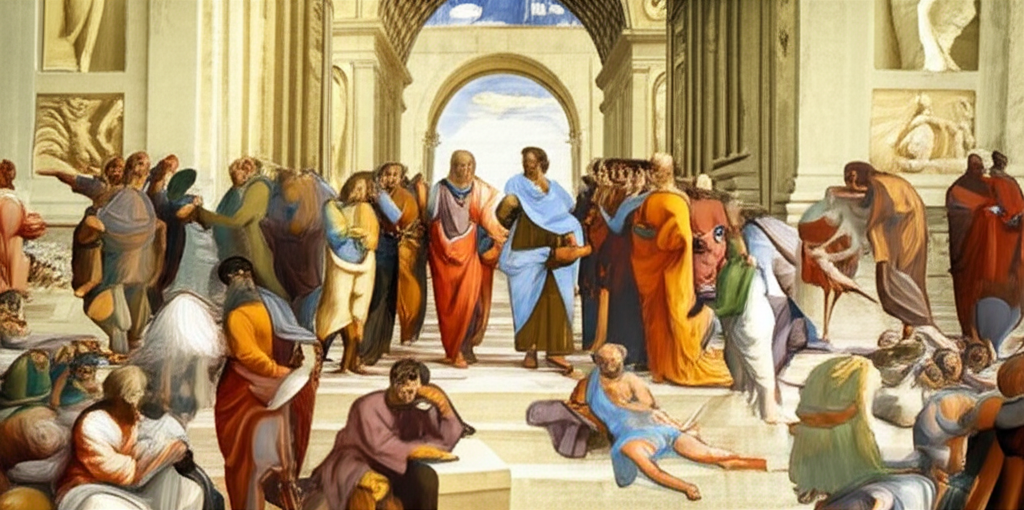

C. Plato's Forms: Bridging the Divide

It was Plato, profoundly influenced by both Parmenides and Heraclitus, who offered perhaps the most enduring attempt to reconcile the One and the Many. Plato proposed his theory of Forms, or Ideas.

For Plato:

- The Forms (the One): These are eternal, unchanging, perfect, and singular essences (e.g., the Form of Beauty, the Form of Justice, the Form of the Good). They exist in a transcendent realm, accessible only through intellect. Each Form is a perfect Definition of a universal concept.

- Particulars (the Many): These are the imperfect, changing, and multiple objects and events we perceive in the sensible world (e.g., a beautiful person, a just act, a good meal). They "participate" in or "imitate" the Forms.

Plato's theory established a crucial Relation between the two realms: the Many derive their reality and intelligibility from their connection to the One (the Forms). This allowed for both the stability of universal truths and the diversity of empirical experience.

Key Ancient Approaches to the One and Many

| Philosopher | Primary Stance | Nature of the "One" | Nature of the "Many" | Core Relation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parmenides | Monism | Absolute Being | Illusion | No true relation; Many is unreal. |

| Heraclitus | Pluralism/Flux | Logos (underlying law of change) | Constant Change, Strife | Dynamic interplay within a unified process. |

| Plato | Dualism | Eternal Forms | Imperfect Particulars | Participation, Imitation |

III. Aristotle's Synthesis: Substance and Predication

Aristotle, Plato's most famous student, critically re-evaluated the problem. While acknowledging the need for universal concepts, he rejected Plato's separate realm of Forms. For Aristotle, the One (the universal) and the Many (the particulars) were not separate entities but intrinsically linked within the very fabric of existence.

Aristotle's solution revolved around his concepts of substance and predication.

- Primary Substance: This is the individual, particular thing (e.g., this horse, that human). It is the ultimate subject of predication, the concrete existent. This represents the Many.

- Secondary Substance (Species and Genus): These are the universal categories (e.g., "horse," "animal") that can be predicated of primary substances. They represent the One.

The Relation between the One and the Many, for Aristotle, is found in the way universals are immanent in particulars. The universal "humanity" does not exist in a separate realm but exists in individual humans. We understand the world by abstracting universals from particulars, allowing us to form Definitions and make sense of the diverse world.

IV. Medieval Elaborations: Universals and Particulars

The problem of the One and Many continued to evolve in medieval philosophy, primarily manifesting as the "problem of universals." This debate centered on the ontological status of general concepts (the One) in Relation to individual things (the Many).

- Realism: Argued that universals (like "humanity" or "redness") exist independently of individual things, either as Platonic Forms (extreme realism) or within things themselves (moderate realism, following Aristotle).

- Nominalism: Contended that universals are merely names or mental concepts, with no independent existence outside of the particular things they describe. Only the Many are truly real.

- Conceptualism: A middle ground, suggesting universals exist as concepts in the mind, abstracted from particulars, but without independent external reality.

This medieval discourse further refined the Definition of the problem, exploring the intricate Relation between language, thought, and reality in understanding unity and multiplicity.

V. Modern Perspectives: Identity, Difference, and Systems

The Enlightenment and subsequent philosophical movements brought new dimensions to the One and Many.

- Spinoza's Monism: Baruch Spinoza famously argued that there is only one substance—God or Nature—which is infinite, eternal, and constitutes all reality. Everything we perceive as distinct is merely an attribute or mode of this single, ultimate One.

- Leibniz's Monads: Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, in contrast, proposed a universe composed of countless individual, simple, indivisible substances called monads. Each monad is a "mirror of the universe," reflecting the whole from its unique perspective. Here, the Many are fundamental, yet they operate in a pre-established harmony, hinting at a larger, divine One.

- Hegel's Dialectic: G.W.F. Hegel offered a dynamic understanding of the Relation between the One and Many through his dialectical method. He saw reality as a process of becoming, where the One (thesis) differentiates into the Many (antithesis), only to be synthesized into a higher, more complex unity. This process illustrates how unity and diversity are not static opposites but interdependent moments in the unfolding of truth.

VI. The Metaphysical Relation: Unity Amidst Diversity

Ultimately, the problem of the One and Many is less about choosing one over the other, and more about understanding their intricate Relation. It is the search for a coherent framework that can account for both the distinctness of individual entities and their membership in larger wholes, categories, and systems.

This Metaphysics problem forces us to confront fundamental questions:

- How do we define identity in a world of constant change?

- What constitutes a whole when it is composed of parts?

- How can universal truths apply to particular instances?

The various philosophical attempts, from ancient Greek thought to modern systems, represent a continuous effort to provide a Definition of reality that honors both its unified structure and its diverse manifestations. Whether through transcendent Forms, immanent universals, or dialectical processes, philosophers have sought to map the profound Relation between the singular and the plural, striving to make sense of the cosmos and our place within it.

Conclusion

The journey through the philosophical landscape of the One and Many reveals a persistent and profound inquiry into the very nature of existence. From the rigid monism of Parmenides to the dynamic dialectics of Hegel, thinkers have wrestled with the fundamental paradox of unity amidst diversity. This core Metaphysics problem remains central to our understanding of knowledge, language, ethics, and indeed, reality itself. The ongoing quest for a comprehensive Definition of the Relation between the singular and the plural continues to inspire and challenge, reminding us that the deepest philosophical questions are often those that appear most simple, yet unravel into infinite complexity.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Theory of Forms Explained""

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Aristotle Metaphysics One and Many""