Causality's Enduring Enigma: Bridging Physics and Metaphysics

Causality, the fundamental relationship between a cause and its effect, forms the bedrock of our understanding of the universe. From the simplest observation of a pushed object moving to the most intricate scientific theories, we instinctively seek the cause behind every phenomenon. Yet, this seemingly straightforward concept unravels into profound complexities when examined through the twin lenses of Physics and Metaphysics. This article delves into how these distinct yet intertwined disciplines approach causality, exploring the descriptive power of scientific laws alongside the deep philosophical questions about the very nature of cause, the necessity and contingency of events, and the ultimate fabric of reality.

The Physical Lens: Describing "How" the Universe Unfolds

In the realm of Physics, causality primarily concerns the observable, measurable relationships between events. It seeks to establish predictive models and laws that describe how one event leads to another.

Classical Determinism: Predictable Chains of Events

For centuries, classical physics, epitomized by Isaac Newton's laws of motion and universal gravitation, presented a deterministic view of the universe. Here, every effect has a preceding cause, and given sufficient knowledge of initial conditions, the future state of the universe could, in principle, be predicted with absolute certainty.

- Newtonian Mechanics: A force (cause) applied to an object results in acceleration (effect). The trajectory of a projectile is precisely determined by its initial velocity and the force of gravity. This framework emphasizes efficient cause – the agent or event that brings about a change.

- Conservation Laws: Energy, momentum, and charge are conserved, implying a continuous, causal chain where properties are transferred or transformed, never arbitrarily appearing or disappearing.

This perspective imbues causality with a strong sense of necessity: if the cause occurs, the effect must follow. The universe is a grand, intricate clockwork mechanism.

Quantum Challenges: Probability and Indeterminacy

The advent of quantum physics in the 20th century introduced a radical shift, challenging the classical notion of deterministic causality. At the subatomic level, events often appear probabilistic rather than absolutely determined.

- Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle: Certain pairs of properties (like position and momentum) cannot be known with perfect precision simultaneously. This isn't just a limitation of measurement; it suggests an inherent indeterminacy.

- Wave Function Collapse: The act of observation seems to "collapse" a particle's wave function into a definite state, raising questions about whether the observation itself is a cause or merely reveals a pre-existing (but indeterminate) reality.

- Probabilistic Outcomes: Radioactive decay, for instance, cannot be predicted for an individual atom, only for a large ensemble. We know the cause (unstable nucleus) but the effect (decay at a specific time) is fundamentally uncertain.

While quantum physics doesn't abandon causality entirely (events don't happen without any reason), it suggests a more nuanced, probabilistic form of causal connection, where necessity is replaced by statistical likelihood, and some events might be truly contingent in their specific manifestation.

The Metaphysical Lens: Probing "Why" and "What" is a Cause

Where physics describes the mechanisms of causality, metaphysics delves into its deeper nature: What is a cause? Does it exist independently of our perception? What kind of necessity binds cause and effect?

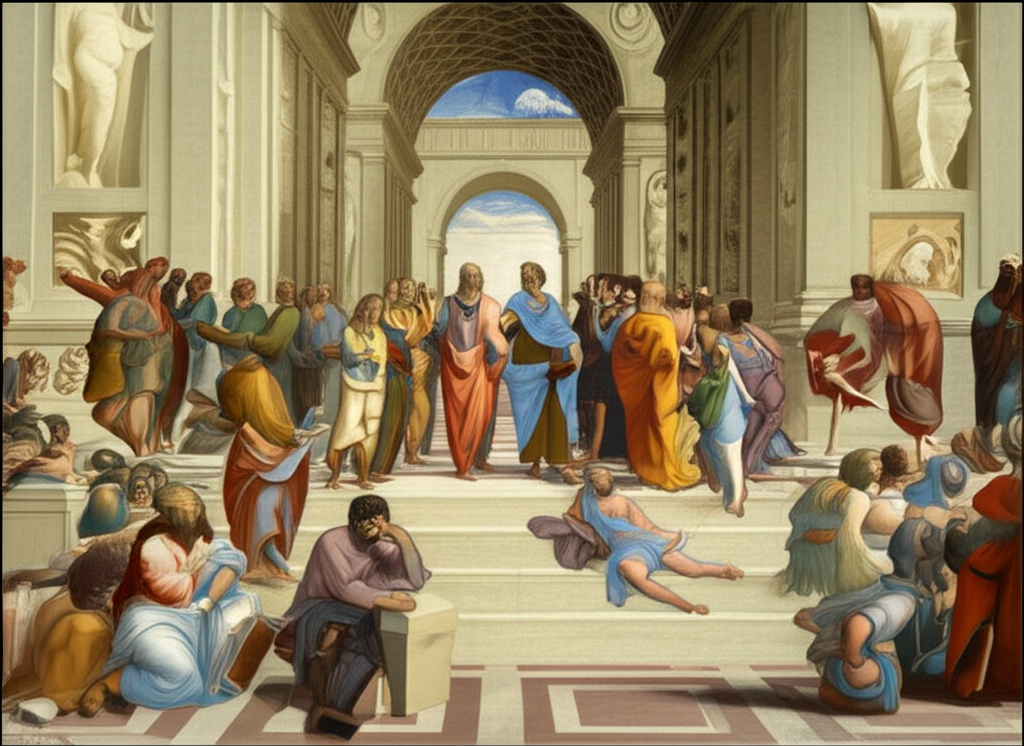

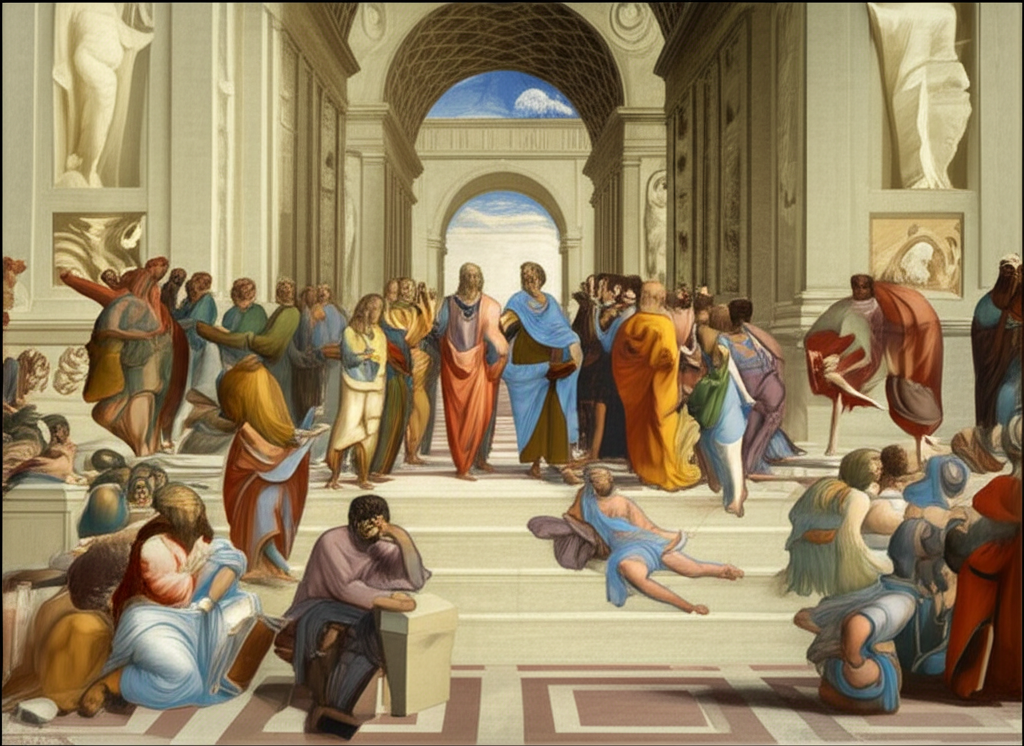

Aristotle's Four Causes: A Comprehensive Framework

One of the earliest and most enduring metaphysical explorations of cause comes from Aristotle, whose framework, detailed in works like Physics and Metaphysics (part of the Great Books of the Western World), identifies four distinct types of causes:

| Type of Cause | Description | Example (Sculpture) |

|---|---|---|

| Material Cause | That out of which something is made. | The bronze or marble used for the statue. |

| Formal Cause | The essence or blueprint; the shape or structure. | The idea or design of the statue in the artist's mind. |

| Efficient Cause | The primary source of the change or rest; the agent. | The sculptor carving or casting the material. |

| Final Cause | The end, purpose, or goal for which something exists or is done. | The statue's purpose: to honor a hero, to be beautiful. |

Aristotle's schema highlights that understanding a phenomenon fully requires considering multiple causal factors, moving beyond just the immediate efficient cause that physics often focuses on. His final cause, in particular, introduces the idea of teleology – purpose-driven causality – which has been a major point of philosophical debate.

Hume's Skepticism: Custom, Not Necessity

David Hume, an 18th-century Scottish philosopher, launched a profound challenge to the notion of causal necessity. In his An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (also a Great Book), Hume argued that we never actually observe a "necessary connection" between a cause and its effect.

- Constant Conjunction: We only ever perceive that event A is regularly followed by event B. The billiard ball striking another (A) is always followed by the second ball moving (B).

- No Sensory Impression of Necessity: We don't have a sensory impression of the "power" or "force" that necessitates B following A.

- Habit and Expectation: Our belief in causality, Hume concluded, is largely a product of custom and habit. After repeated observations, our minds develop an expectation that B will follow A, but this is a psychological phenomenon, not an objective feature of the world.

For Hume, the link between cause and effect is ultimately contingent – it just so happens to be that way, and we cannot logically prove that it must be that way in the future. This raised the specter of radical skepticism, questioning the very foundation of scientific induction.

Kant's Response: Causality as a Category of Understanding

Immanuel Kant, deeply influenced by Hume, sought to rescue causality from skepticism. In his Critique of Pure Reason (Great Books), Kant argued that causality is not something we derive from experience, but rather a fundamental category of understanding that our minds impose upon experience to make sense of it.

- A Priori Condition: For Kant, the principle that every event must have a cause is an a priori truth, meaning it's known independently of experience and is a necessary condition for our experience of an objective, ordered world.

- Synthetic A Priori Judgment: It's a "synthetic" judgment because it adds new information (that events are necessarily connected), but it's "a priori" because it's universally and necessarily true for all rational beings.

- Structuring Experience: We don't find causality in the world, but rather, we perceive the world through the lens of causality. Without this innate mental structure, experience would be a chaotic, meaningless succession of events.

For Kant, the necessity of the causal link is not out there in things-in-themselves, but rather in the very structure of our minds, allowing us to construct a coherent, objective reality.

Intersections and Divergences: A Shared Inquiry

The relationship between physics and metaphysics concerning causality is one of constant dialogue and tension.

- Physics informs Metaphysics: Scientific discoveries, particularly in quantum mechanics, force metaphysicians to re-evaluate traditional notions of necessity and contingency, determinism, and the very nature of reality. If quantum events are truly probabilistic, what does that mean for free will or the predictability of the universe?

- Metaphysics underpins Physics: Even the most empirical physics relies on certain metaphysical assumptions. The belief that the universe is orderly, that natural laws are consistent, and that experiments can reveal objective truths about cause and effect are all, at some level, metaphysical commitments. The very act of seeking explanations implies a belief in causal structure.

- The Unanswered "Why": While physics excels at describing how gravity causes objects to fall, metaphysics continues to ask why there is gravity at all, or what it fundamentally means for one thing to "cause" another. The deep questions about the ultimate nature of force, energy, and spacetime remain fertile ground for philosophical inquiry.

The concept of cause thus serves as a crucial bridge and a persistent battleground between scientific description and philosophical understanding. It challenges us to look beyond immediate observations and ponder the deeper structures of reality and our minds.

Conclusion: The Enduring Mystery of the Causal Link

From the predictable dance of planets to the probabilistic flicker of subatomic particles, and from Aristotle's fourfold analysis to Hume's skepticism and Kant's transcendental synthesis, causality remains one of philosophy's most profound and enduring mysteries. Physics provides us with powerful tools to predict and manipulate the world by understanding causal mechanisms. Yet, it is metaphysics that continuously pushes us to question the very essence of that causal link, probing its necessity and contingency, and asking what it truly means for one thing to bring another into being. As we continue to explore the universe, the quest to understand cause will undoubtedly remain at the heart of both scientific and philosophical endeavor.

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Hume's problem of induction and causality explained""

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Aristotle's Four Causes explained simply""