Astronomy and the Concept of the World

From the earliest stargazers to the modern astrophysicist, astronomy has relentlessly reshaped our understanding of the "World" – not merely as the Earth we inhabit, but as the grand cosmic stage upon which existence unfolds. This article explores how our evolving astronomical insights have profoundly influenced philosophical thought, forcing us to redefine Space, Time, and ultimately, our place within the universe. Through the lens of historical shifts, we will see how the celestial dance has consistently challenged and expanded humanity's most fundamental metaphysical and epistemological assumptions about reality itself.

The Ancient Cosmos: A Finite, Earth-Centric World

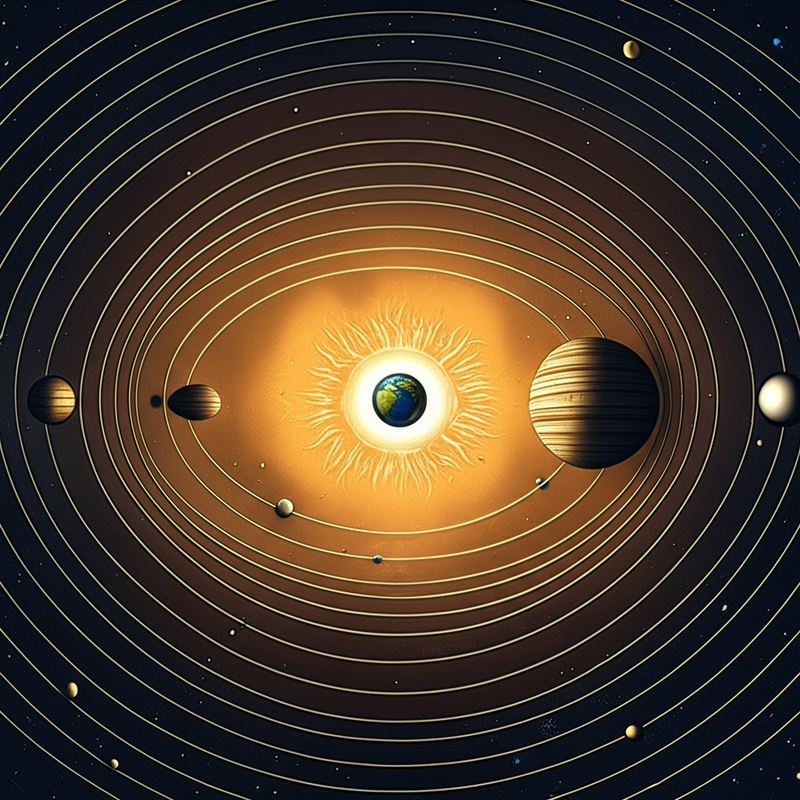

For millennia, the "World" was understood through the elegant, if ultimately incorrect, model of a geocentric universe. Rooted in the philosophies of Aristotle and meticulously codified by Ptolemy in his Almagest (a foundational text within the Great Books of the Western World), this view placed Earth, and by extension humanity, at the unmoving center of creation.

- Aristotelian Cosmology: The cosmos was divided into two distinct realms:

- Sublunary Sphere: Imperfect, changeable, composed of earth, water, air, and fire. This was our World.

- Supralunary Sphere: Perfect, immutable, composed of a divine fifth element (aether), where celestial bodies moved in perfect circles around the Earth.

- Concept of Space: Finite, hierarchical, and qualitative. The "natural place" of elements defined its structure.

- Concept of Time: Often seen as cyclical, tied to the predictable motions of the heavens, yet also linear within the sublunary realm.

This model provided a comforting, ordered "World" where divine purpose was evident in the celestial machinery. Humanity, positioned at the center, held a special, if fallen, status.

The Copernican Revolution: A World Displaced

The 16th and 17th centuries witnessed a paradigm shift that irrevocably shattered the ancient geocentric "World." Nicolaus Copernicus, in his De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, dared to propose a heliocentric model, placing the Sun, not the Earth, at the center of the planetary system. This wasn't merely an astronomical adjustment; it was a profound philosophical earthquake.

Key Shifts Initiated by Heliocentrism:

| Feature | Geocentric "World" (Ptolemy/Aristotle) | Heliocentric "World" (Copernicus/Galileo) |

|---|---|---|

| Center of Cosmos | Earth | Sun |

| Humanity's Place | Central, special | Peripheral, less unique |

| Nature of Heavens | Perfect, immutable, divine | Imperfect, material, subject to change |

| Space | Finite, qualitative, hierarchical | Potentially infinite, uniform, quantitative |

| Time | Linked to divine order, cyclical/linear | More mechanistic, measurable, linear |

Galileo Galilei's telescopic observations, documenting lunar craters and Jupiter's moons, provided empirical evidence that directly contradicted Aristotelian perfection. Johannes Kepler's laws of planetary motion, describing elliptical orbits, further dismantled the notion of perfect circles, introducing mathematical elegance that defied intuitive perfection. The "World" was no longer a divinely ordered hierarchy but a dynamic, physically governed system.

Newton's Universe: A Clockwork World in Infinite Space

Isaac Newton's Principia Mathematica (another cornerstone of the Great Books) synthesized these discoveries into a grand, mechanistic worldview. His law of universal gravitation explained the motions of both celestial bodies and earthly objects with a single, elegant principle.

- The "World" as a Machine: Newton's universe was a vast, orderly, and predictable machine, governed by universal, immutable laws. This concept of the "World" fostered a sense of rational comprehension and predictability.

- Absolute Space and Time: Newton posited the existence of absolute Space – an infinite, unmoving container – and absolute Time – a uniformly flowing duration, independent of events. This provided a rigid framework for understanding the cosmos.

- Philosophical Impact: This mechanistic "World" fueled the Enlightenment, emphasizing reason, empirical observation, and the search for universal laws. It profoundly influenced thinkers like Locke and Kant, who grappled with the implications for human knowledge and freedom within such a deterministic universe.

The Modern Cosmos: Relativity, Quantum, and the Expanding World

The 20th century, propelled by Albert Einstein's theories of relativity and the advent of quantum mechanics, once again shattered our stable "World" concepts.

- Relativistic Space-Time: Einstein's work dissolved Newton's absolute Space and Time into a unified, dynamic space-time fabric, warped by mass and energy. The "World" became relative, observer-dependent, and far more intricate.

- An Expanding Universe: Edwin Hubble's observations of distant galaxies moving away from us revealed that the entire "World" – the universe itself – is expanding. This added a dynamic, evolving dimension to our cosmic understanding, challenging static models.

- The Quantum World: On the smallest scales, quantum mechanics introduced probabilities, uncertainty, and non-local connections, suggesting that our intuitive understanding of reality breaks down. The "World" at its most fundamental level is stranger than we could have imagined.

- Exoplanets and Multiverses: Contemporary astronomy continues to push boundaries. The discovery of thousands of exoplanets suggests that Earth-like worlds might be common, broadening our concept of "World" to include countless potential habitats. Theoretical physics even entertains the notion of multiverses, hinting at a reality far grander and more diverse than our single universe.

Conclusion: An Ever-Evolving Concept of the World

From the finite, Earth-centric cosmos of the ancients to the expanding, relativistic, and quantum-infused universe of today, astronomy has been the primary driver of humanity's evolving concept of the "World." Each new discovery has forced philosophy to re-evaluate our notions of Space, Time, causality, and our own significance. The journey from Ptolemy's spheres to the contemplation of dark matter and exoplanets is not just a scientific progression, but a continuous philosophical re-imagining of what constitutes "the World" – a testament to the enduring human quest to understand the vastness both without and within.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Cosmos Carl Sagan Pale Blue Dot"

2. ## 📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Brian Greene fabric of the cosmos"