Aristocracy, Honor, and the Fabric of Society

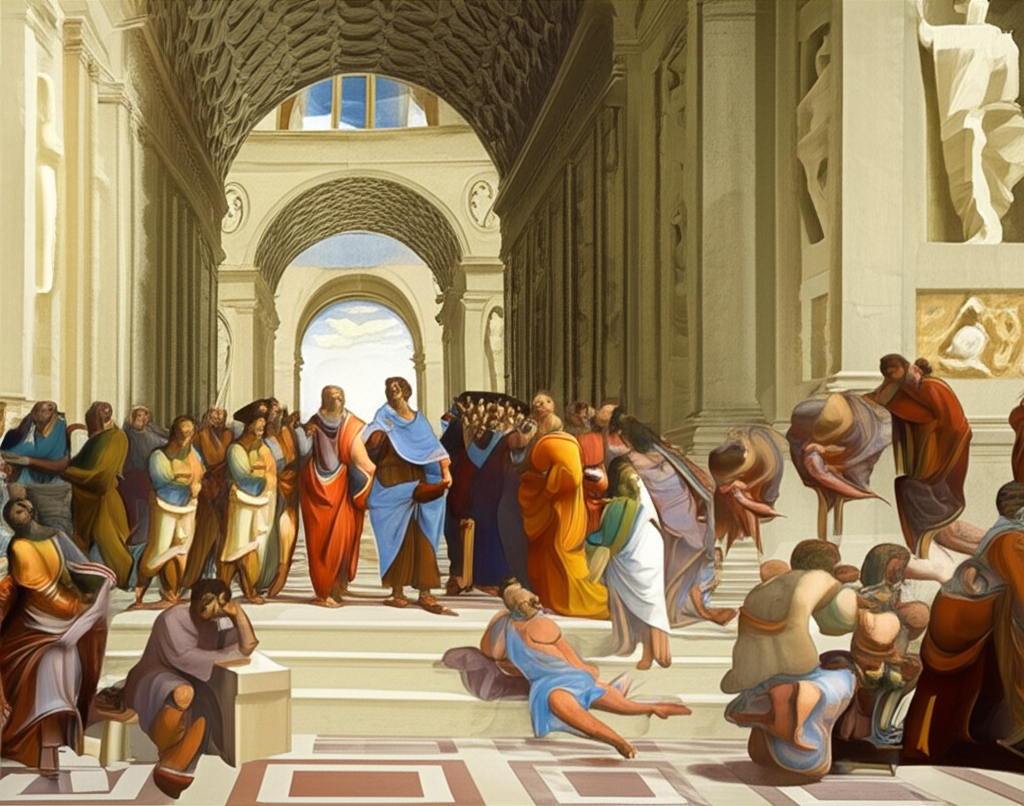

The concept of aristocracy, often misconstrued as mere rule by birthright, originally signified governance by the "best" – those deemed most virtuous, wise, and courageous. Central to this ideal form of government was an intricate and demanding code of honor, which served not only as a personal moral compass but also as the bedrock of custom and convention within society. This article explores the profound interrelationship between aristocracy and honor, drawing insights from the foundational texts of the Great Books of the Western World, revealing how this powerful combination shaped political thought, social structures, and individual conduct for centuries.

The Etymology of Excellence: What is Aristocracy?

At its root, aristocracy stems from the Greek words aristoi (the best) and kratos (rule), literally meaning "the rule of the best." This definition immediately elevates the concept beyond simple hereditary privilege, pointing instead to a meritocratic ideal where leadership is entrusted to those possessing superior qualities – intellectual, moral, or martial.

Plato, in his seminal work The Republic, envisioned an ideal state governed by philosopher-kings, individuals whose wisdom and virtue made them uniquely qualified to lead. While he also described a "timocracy" as a government motivated by honor and ambition, his highest form of rule, the aristocracy, was predicated on the pursuit of justice and truth. Aristotle, in his Politics, likewise distinguished between the virtuous forms of government and their corrupt counterparts, classifying aristocracy as a just rule by a few for the common good, as opposed to oligarchy, which served only the wealthy elite. The "best" were those whose character and actions aligned with the highest ideals of the community.

Honor: The Guiding Star of the Elite

Within an aristocratic framework, honor was not merely a desirable trait; it was an indispensable qualification, a currency of social standing, and a deeply internalized code of conduct. It encompassed a complex web of personal integrity, public reputation, and an unwavering commitment to duty.

Personal Virtue and Public Esteem

For the aristoi, honor was a constant challenge to live up to a higher standard. It demanded:

- Integrity and Truthfulness: A man of honor was expected to be true to his word, his oaths, and his principles, even at great personal cost.

- Courage and Martial Prowess: Especially in earlier aristocratic societies, honor was inextricably linked to bravery in battle and the defense of one's community. Homer's Iliad is replete with heroes like Achilles and Hector whose entire existence is defined by their pursuit and defense of honor (kleos, or undying glory).

- Generosity and Magnanimity: An honorable aristocrat was often expected to be a patron of the arts, a benefactor to the less fortunate, and to display a noble spirit in victory and defeat.

- Dignity and Self-Respect: Maintaining an outward demeanor of composure and self-possession, even under duress, was a hallmark of honorable conduct.

Duty, Sacrifice, and Kleos

The pursuit of honor often meant prioritizing the collective good over individual comfort or even life. The concept of noblesse oblige – the unspoken obligation of the nobility to act honorably and responsibly – exemplified this duty. An aristocrat's honor was not solely their own; it was tied to their family, their lineage, and their community. To dishonor oneself was to dishonor all who came before and would come after. This profound sense of duty, often demanding sacrifice, was a core tenet of aristocratic honor.

Government by the Honorable: Ideal and Reality

The belief that honor was essential for good government meant that the ruling class was theoretically bound by a higher moral standard. Montesquieu, in The Spirit of the Laws, argued that honor was the animating principle of monarchies, which often relied on an aristocratic class. He posited that the unique demands of honor – the pursuit of distinction, the fear of shame, and adherence to specific codes – could serve as a check on the monarch's power and motivate the nobility to public service.

Table: Aristocratic Honor in Governance

| Aspect of Honor | Impact on Government | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Integrity | Fosters trust in leadership; discourages corruption. | Ideal Platonic Guardian |

| Duty & Service | Motivates public service; prioritizes common good. | Roman Cincinnatus returning to farm after dictatorship |

| Courage | Ensures defense of the state; decisiveness in crisis. | Homeric heroes leading in battle |

| Reputation (Fear of Shame) | Acts as a powerful deterrent against tyranny or injustice. | Montesquieu's principle for monarchy |

While the ideal was a government guided by selfless honor, reality often diverged. The hereditary nature of many aristocracies could lead to rule by the unworthy, where privilege overshadowed actual virtue. Yet, even in its corrupted forms, the language and expectation of honor persisted, providing a framework against which rulers could be judged.

Custom and Convention: Weaving Honor into Daily Life

The abstract concept of honor found its concrete expression through custom and convention. These societal norms, rituals, and unwritten rules served to uphold and reinforce the aristocratic code.

- Chivalric Codes: In medieval Europe, the intricate codes of chivalry dictated the behavior of knights and nobles, encompassing bravery, courtesy, loyalty, and protection of the weak. Jousts, tournaments, and courtly love were all conventions designed to display and reinforce these honorable traits.

- Duelling: Though often violent and ultimately outlawed, the practice of duelling was a stark manifestation of honor culture. It represented a personal defense of one's reputation against perceived insult or slander, demonstrating a willingness to risk life for one's standing.

- Etiquette and Protocol: Elaborate rules of social interaction, from courtly manners to formal addresses, served to maintain social hierarchy and reinforce the dignity associated with aristocratic status. Deviations could be seen as dishonorable and lead to social ostracism.

- Lineage and Heritage: Custom and convention dictated that an aristocrat's honor was deeply intertwined with their ancestors. Upholding family honor meant living in a way that reflected credit upon one's heritage and ensuring a good name for future generations.

These conventions, passed down through generations, created a powerful social pressure to conform. The fear of shame, disgrace, or social ruin was a potent motivator, often more compelling than legal sanctions, in maintaining the aristocratic order.

The Enduring Legacy of Honor

While traditional aristocracies have largely faded from the political landscape, the concept of honor they championed has not entirely disappeared. It has transmuted into various forms, influencing military codes, professional ethics, and even personal moral frameworks. The questions posed by the Great Books of the Western World regarding the ideal ruler, the nature of virtue, and the role of the individual in society remain profoundly relevant, prompting us to consider what qualities we truly value in our leaders and ourselves. The historical interplay of aristocracy and honor offers a rich tapestry for understanding the evolution of governance and the enduring human quest for excellence.

Conclusion: A Reflection on Nobility

The historical relationship between aristocracy and honor is a complex narrative of ideals and imperfections. While the aristocratic ideal of "rule by the best" often succumbed to the realities of inherited privilege and power, the accompanying code of honor provided a powerful, if sometimes rigid, framework for government, custom and convention. From the heroic quests for kleos in ancient epics to the intricate social rituals of later centuries, honor served as the animating spirit, demanding integrity, courage, and a profound sense of duty. Reflecting on this historical connection allows us to critically examine the virtues and vices inherent in systems that place a premium on a select few, and to ponder what true nobility might entail in our own time.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Republic Aristocracy Philosophy" "Montesquieu Honor Principle Monarchy""