Aristocracy and the Concept of Honor: A Philosophical Reflection

Summary

Historically, the concept of aristocracy was deeply intertwined with an idealized notion of honor. Far from simply denoting inherited status, genuine aristocracy—meaning "rule by the best"—was envisioned as a form of government guided by a moral imperative, where the ruling elite were bound by a strict code of honor. This code, enforced through custom and convention, served as both a personal virtue and a public standard, theoretically ensuring justice, courage, and integrity in governance. This article explores the philosophical underpinnings of this connection, drawing insights from the Great Books of the Western World.

The Noble Ideal: Defining Aristocracy Beyond Birthright

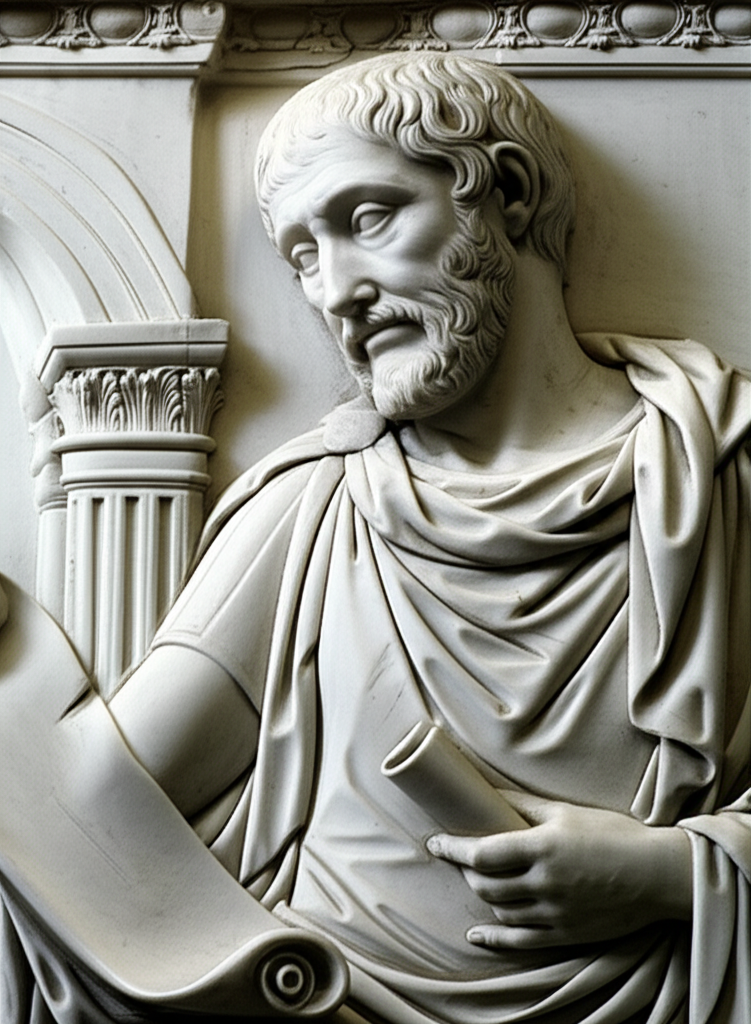

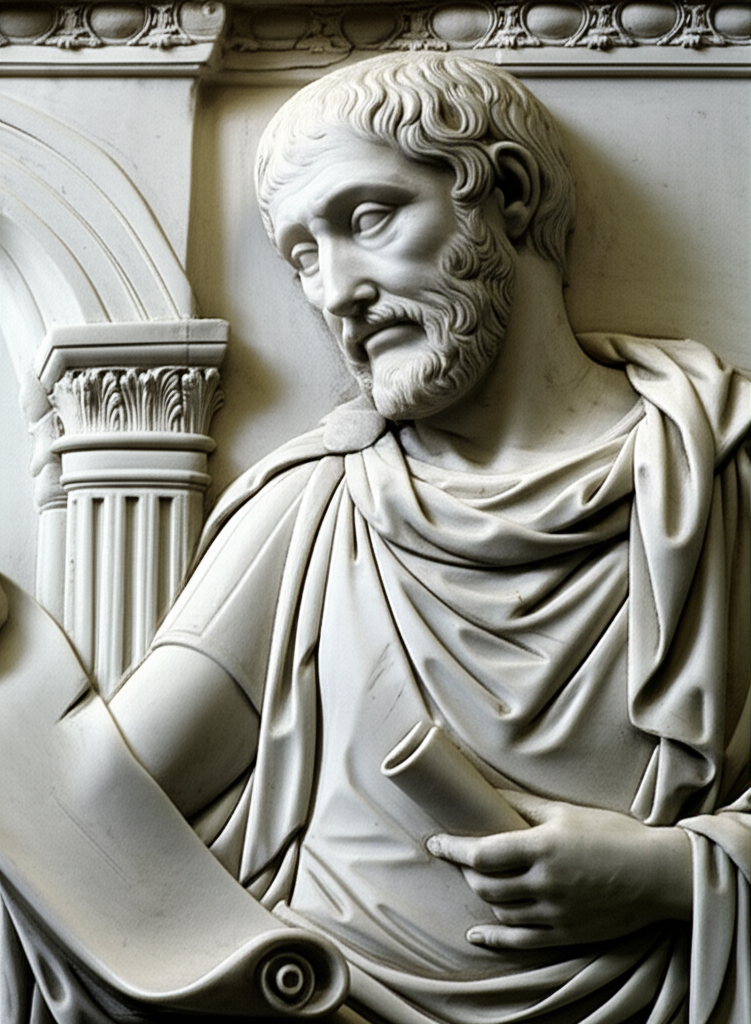

When we speak of aristocracy today, we often conjure images of inherited wealth, privilege, and perhaps a touch of anachronistic pomp. However, the philosophical origins of the term, derived from the Greek aristokratia, point to something far more profound: rule by the best. For thinkers like Plato and Aristotle, an aristocracy was not merely a government by a select few, but specifically by those few who were most virtuous, most capable, and most dedicated to the common good.

This ideal form of government demanded an extraordinary commitment from its rulers. It was here that the concept of honor became not just a desirable trait, but the very bedrock of aristocratic legitimacy. An aristocrat, in this classical sense, was not born into honor, but was expected to earn and uphold it through their actions, decisions, and character.

Honor: The Guiding Star of the Aristocratic Soul

What, then, constituted this pivotal honor? It was a multifaceted concept, encompassing:

- Virtue (Arete): Moral excellence, courage, justice, temperance, and wisdom. For Aristotle, these virtues were the very essence of human flourishing and the hallmark of a truly "best" individual.

- Reputation and Esteem: Public acknowledgment of one's virtuous conduct. Loss of honor meant not just personal shame, but a diminished capacity to lead or command respect.

- Duty and Responsibility: A profound sense of obligation to the community, often expressed through military service, public office, and philanthropic endeavors.

- Integrity and Truthfulness: Adherence to one's word and principles, even in the face of adversity.

This was an honor that transcended mere personal pride; it was a public trust. The aristocrat's honor was inextricably linked to the well-being of the state. A ruler without honor was, by definition, unfit to rule, as their actions would inevitably devolve into self-interest or tyranny.

Aristocracy and Forms of Government: A Spectrum of Rule

The Great Books offer a nuanced view of how aristocracy manifested in different forms of government.

| Form of Government | Ruling Principle | Role of Honor | Degenerate Form |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ideal Aristocracy | Virtue, Wisdom | Paramount: Guarantees just rule and public service | Oligarchy, Tyranny |

| Oligarchy | Wealth, Property | Subverted: Honor becomes mere display or means to acquire more wealth | (Further degradation into tyranny) |

| Timocracy | Military Valor, Honor (as ambition) | Central, but can lead to excessive ambition or war | (Can devolve into oligarchy) |

Plato, in his Republic, explores the ideal of philosopher-kings, an intellectual aristocracy whose rule is guided by reason and a deep understanding of the Good. While not hereditary, their rule is aristocratic in its purest sense—governance by the "best" minds for the sake of justice. Aristotle, in Politics, discusses aristocracy as a rule by the virtuous few, contrasting it with oligarchy (rule by the wealthy) and democracy (rule by the many), which he viewed as potentially unstable or prone to corruption if not tempered by virtue.

The degeneration of aristocracy into oligarchy or tyranny was often seen as a failure of honor. When the pursuit of wealth or power eclipsed the commitment to virtue and public duty, the noble ideal collapsed.

The Guardians of Virtue: Custom and Convention

The abstract ideal of honor was made tangible and enforceable through the intricate web of custom and convention. These unwritten rules, traditions, and societal expectations were the very mechanisms by which aristocratic societies maintained their moral standards.

- Social Expectations: An aristocrat was expected to exhibit certain behaviors—courage in battle, generosity in peace, eloquence in debate, and dignity in bearing. Failure to conform brought public disapprobation.

- Codes of Chivalry: In medieval Europe, the knightly code was a prime example of honor codified by custom. It demanded loyalty, courtesy, bravery, and protection of the weak.

- Duels and Public Challenge: While often violent, the duel, in certain historical contexts, served as a desperate and extreme mechanism for defending one's honor and reputation against perceived slights, reinforcing the seriousness with which honor was held.

- Family Reputation: An individual's honor was often inextricably linked to their family line, creating a powerful incentive to uphold virtuous conduct lest one bring shame upon one's ancestors and descendants.

These customs and conventions created a powerful social pressure, ensuring that the pursuit of honor was not merely an individual endeavor but a collective responsibility. They were the invisible architecture supporting the visible structures of aristocratic government.

The Enduring Legacy of Honor in a Modern World

The decline of traditional aristocracy as a dominant form of government did not eradicate the concept of honor. Instead, it transformed. While the specific customs and conventions that once upheld aristocratic honor may have faded, the underlying principles of integrity, duty, and public service remain vital for any healthy society.

Modern democracies grapple with their own versions of "rule by the best," often seeking leaders who embody a sense of public honor and commitment to the common good. The historical interplay between aristocracy and honor serves as a powerful reminder that leadership, in its most idealized form, is not merely about power or privilege, but about a profound moral responsibility to those one governs. The echoes of this ancient ideal continue to shape our expectations of ethical leadership and virtuous citizenship, prompting us to reflect on what it truly means to be "the best" in service to humanity.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Republic: Justice and the Ideal State""

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Aristotle Politics: Forms of Government and the Best Life""