Aristocracy and the Concept of Honor: A Philosophical Examination

Summary: The concept of Aristocracy, literally "rule by the best," is inextricably linked to Honor. Far from simply denoting inherited status, true aristocracy, as envisioned by classical philosophers, demands a commitment to virtue, excellence, and public service, all underpinned by a profound sense of Honor. This article explores how honor served as both a guiding principle and a social currency within aristocratic Government, shaped by Custom and Convention, and how its evolution reflects shifting ideals of leadership and societal value. We will delve into the philosophical roots of this connection, examining how the pursuit and preservation of honor defined the aristocratic ethos and influenced the very fabric of ancient and classical political thought.

I. The Ideal of Aristocracy: Rule by the "Best"

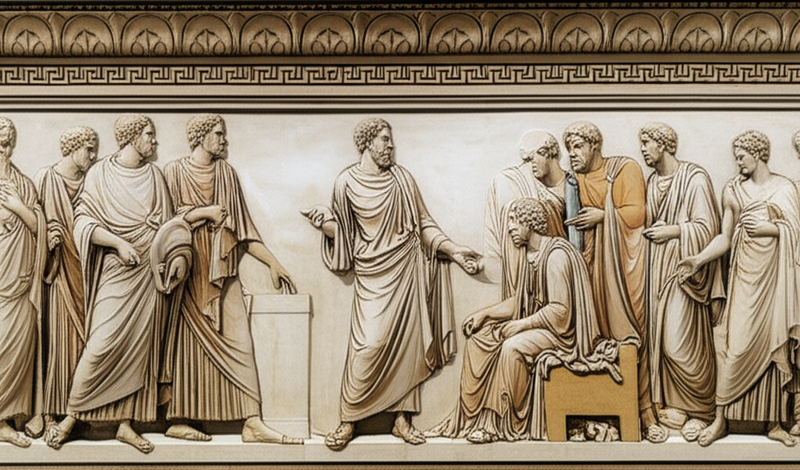

When we speak of Aristocracy in its philosophical sense, particularly as explored in the Great Books of the Western World, we are not merely referring to a system of hereditary rule or a class defined by wealth. Instead, we encounter an ideal form of Government where power resides with those deemed most virtuous, capable, and wise – the "best" (aristoi).

- Plato's Vision: In his Republic, Plato sketches an ideal state ruled by philosopher-kings, individuals whose lives are dedicated to truth, justice, and the common good. Their authority is not derived from birthright but from their superior intellectual and moral arete (excellence or virtue). For these rulers, personal gain is secondary; their primary motivation is the pursuit of the good for the entire polis.

- Aristotle's Nuance: Aristotle, in his Politics, further refines this. While acknowledging that aristocracy can degenerate into oligarchy (rule by the wealthy few), he posits its pure form as a system where citizens rule and are ruled in turn, with the aim of promoting virtue. He distinguishes it from other forms by its focus on the common good and the excellence of its rulers.

This foundational understanding is crucial, for it establishes the fertile ground upon which the concept of Honor blossoms. If the "best" are to rule, what motivates them? What sustains their commitment to virtue? Often, it is honor.

II. Honor as the Aristocratic Ethos

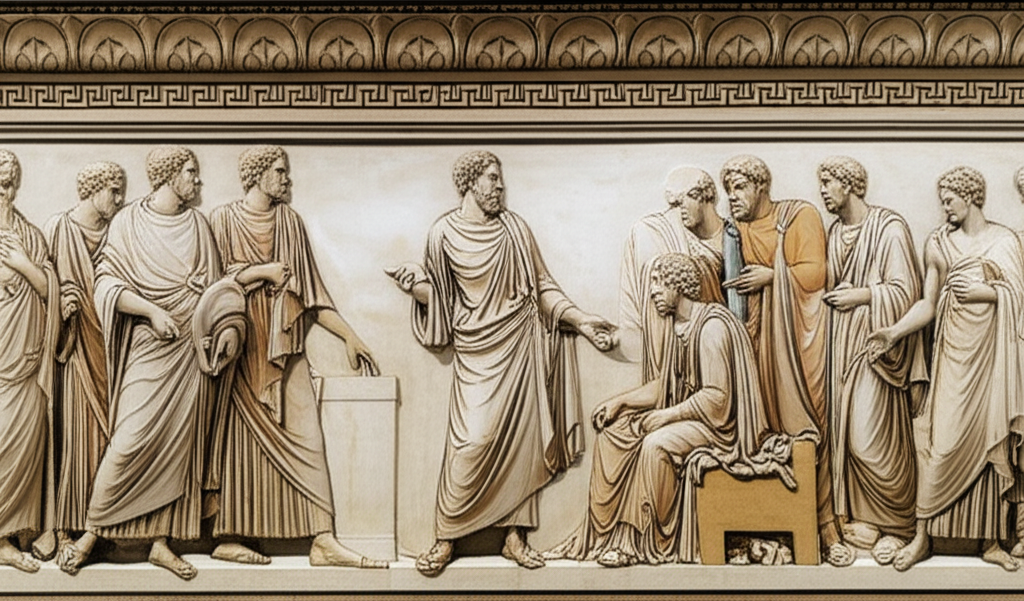

Within aristocratic societies, Honor is more than mere reputation; it is a complex, multifaceted construct that serves as a moral compass, a social regulator, and a deep personal commitment. It is the very essence of the aristocratic spirit.

Facets of Aristocratic Honor:

- Public Esteem: Recognition and respect from one's peers and the community for virtuous actions, courage, and wisdom. This is not vanity, but an acknowledgment of moral worth.

- Internal Integrity: A deep-seated sense of self-respect and adherence to a personal code of conduct, often involving honesty, loyalty, and justice.

- Duty and Responsibility: The understanding that one's elevated position or superior abilities come with significant obligations to serve the community and uphold its values. This is encapsulated in the concept of noblesse oblige.

- Courage and Sacrifice: The willingness to face danger, endure hardship, and even sacrifice personal well-being for the greater good or for cherished principles.

- Adherence to Custom and Convention: Honor is heavily shaped by the unwritten rules, traditions, and expectations of a particular society. Breaching these conventions could lead to profound dishonor, a fate often considered worse than death.

For the aristocrat, the loss of honor was often considered the ultimate catastrophe, signifying a failure not only to oneself but to one's lineage and to the very ideals of the Government they represented. This potent motivator ensured adherence to a high standard of conduct, driven not by law alone, but by the internalized fear of shame and the fervent desire for glory.

III. The Interplay of Honor and Governance

The relationship between Honor and Government in an aristocratic system is symbiotic. Honor provides the moral framework for governance, while the act of governing offers opportunities for the display and earning of honor.

- Motivation for Public Service: The pursuit of honor often drove individuals to seek roles in public life, military leadership, or civic administration. These roles were not primarily for material gain, but for the chance to demonstrate excellence and earn the lasting respect of their fellow citizens.

- Maintaining Social Order: The intricate web of Custom and Convention surrounding honor helped to regulate behavior and maintain social hierarchies. An aristocrat's word, their pledge, or their public conduct was expected to be unimpeachable, lest they bring dishonor upon themselves and their house. Challenges to honor, such as insults or perceived slights, could lead to elaborate rituals of satisfaction, from duels to public apologies, all governed by specific conventions.

- A Check on Power: While honor could be a source of immense power, it also acted as a crucial check. A ruler who acted dishonorably – by being tyrannical, unjust, or corrupt – risked losing the very public esteem that legitimized their rule. This informal yet powerful accountability mechanism was a cornerstone of many aristocratic systems.

- The Dangers of Hubris: However, the pursuit of honor was not without its perils. An excessive focus on personal glory could lead to hubris, transforming virtuous ambition into self-serving vanity. This distortion could lead to factionalism, tyranny, or a disregard for the common good, ultimately undermining the very Aristocracy it was meant to uphold. When honor becomes mere pride, the "best" can quickly devolve into the "most powerful" or "most self-interested."

IV. The Evolution and Erosion of Aristocratic Honor

The classical understanding of Aristocracy and its profound connection to Honor did not remain static. Over centuries, as societies evolved, so too did the meaning and application of these concepts.

- From Classical Virtue to Chivalric Code: In the medieval period, the concept of honor was reinterpreted through the lens of chivalry, emphasizing martial prowess, religious piety, and loyalty to one's lord. While still rooted in Custom and Convention, this form of honor was often more personal and less tied to direct civic Government than its classical predecessor.

- The Rise of Individualism and Meritocracy: With the Enlightenment and the subsequent rise of democratic ideals, the very notion of inherited honor began to be challenged. The emphasis shifted from birthright and traditional Custom and Convention to individual merit, achievement, and equality before the law. The idea of "rule by the best" gradually transformed into "rule by the people," or at least, rule by those who earned their position through demonstrated ability, rather than inherited status.

- Enduring Legacy: Despite the decline of traditional aristocracy, the underlying principles of honor persist. The expectation of integrity, duty, and public service from those in Government leadership, the value placed on one's reputation, and the moral imperative to act justly—these are all echoes of the aristocratic concept of honor that continue to resonate in modern society. We may no longer have aristocrats in the classical sense, but the aspiration for honorable leadership remains a cornerstone of ethical governance.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

- YouTube: "Plato Aristotle ideal government aristocracy honor"

- YouTube: "Great Books Western World honor virtue leadership"

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Aristocracy and the Concept of Honor philosophy"