To the Unknown Man

The unknown man has been a staple of evolution. Without him, nothing from the Pyramids to Stonehenge to today's skyscrapers would have been built. The unknown man does the unknown job to bring the incredible into being.

And that's how I'd like to frame this reflection; throughout history, the unknown man woke up and went out the door to do play his minor part with an orchestra of like-minded men who had nothing special about their workdays except their hands. Whether they held a shovel, rope, or a pipe, hands were their gifts, their strength. The unknown man's hands were the tools of his trade.

(A caveat: I applaud the Unknown Women too, but for purposes of this essay I’m concerned with the Unknown Man, one of whom I have been myself.)

In our cities and towns and villages, someone is responsible for building the footbridge, the pool in the park, the playground near the water fountain, and the homes that make up the community. Someone took pride enough to mix the concrete just right or to plumb the bricks, so the wall went up straight. Millions of men have contributed significant chunks of their time and toil. They have made immense contributions to the well-being of our lives.

The unknown man was from many origins and ethnicities and countries. He may have immigrated from Ireland, Holland or Puerto Rico and may as likely be 5th generation American as a recent arrival. Or he could be indigenous so of longer residency than those of offshore heritage. He may be 15 or 70 years of age. And the black American unknown man was everywhere, building everything, often later not welcomed into the hotels they created or diners they constructed. Many of these unknown men followed the money to cities; they came from rural America in search of work. Unknown men came from small towns to build the superhighways and interstate system that disenfranchised livelihoods in those very hometowns when bypassing them.

I am specifically praising the unknown man who did not get to leave his name behind unless he drew out his initials in wet concrete. I’m thinking of bricklayers, welders, the labourers, the pipe layers, the electricians, and the plasterers. Here’s but one example: much of the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Manhattan required millions of bricks to line the newly designed gridded streets and avenues. The tenements, rowhouses, and apartment buildings that came to define how New Yorkers lived in the 19th century (and still live to this day) also came from the labours of the unknown man. The unknown man took pride in his craftsmanship.

In harder, cheaper times, when a life was often worth whatever skills you had, in an era when safety was one of the least things a builder or contractor cared about, the unknown man often took his life in his hands when he went off to work. There were always plenty of workers should one become injured, sick, or lazy. The unknown man was, at various points in his life, each of these.

The unknown man stopped traffic while another unknown man drove a front-end loader across the street and dumped it at the foot of a group of unknown men with shovels. Whoever he was, wherever he was, he did his job anonymously, pouring concrete into forms, wiring the telephone lines, cutting down trees with axes, painting the side of a building, harvesting a field or mowing a lawn. He washed the windows on a skyscraper, stood on an assembly line, and cleaned chimneys. He drove for a bakery, pulled weeds, or ran new pipes to your toilet. The unknown man did almost every job thinkable and he did it with no fanfare, no legacy; he was there for payday.

They weren't the draftsmen; they were the labourer. They weren't the designer; they were the fabric. They weren't the lender; they were the borrower. They weren't the owner; they were the renter. They weren't the lawyer; they were the client. The unknown man hung off the bottom rungs of society. Yet he was essential.

The unknown man lived many pasts. Maybe he had two healthy parents in a healthy relationship or maybe he had two deadbeat dads and a mother in a recovery house. Maybe he quit school at ten years old to go work in the mines or possibly he went to college but found himself with 20 years invested in the short end of life's stick. Maybe he had a good childhood or a nasty one. Maybe he had a nanny or a family of fighters. Possibly he had a mental illness, a stutter, or panic attacks. Maybe he was shy, introverted, or prejudiced. Just as often, these were average men with average dreams, average families with average lives. And the unknown man did extraordinary things.

The unknown man had to work. Maybe he was broke and there was a 'Help Wanted" sign. Maybe he was released from jail with a list of employers needing "a strong back and a weak mind". Maybe he stood at a corner where workers would pull up in pickup trucks and carry the chosen ones to a worksite. Maybe he sat in a coffee shop wearing old coffee stains on his shirt as he spread open the classifieds, looking for any paying job. Maybe he was in a union, maybe he had a trade, maybe he had his 'ticket', or maybe he was a Jack-of-all-trades. The unknown man had stories, shortcuts, and secrets.

Here’s the stereotype: The unknown man spent his money. Maybe he saved it for a car or to travel, but more often than not, he cared for his family. Often he drank alcohol. One of the greatest tools in the occupational toolkit is also one of its worst: the unknown man could spend a lot of money on Friday night and sleep in Saturday. Again, Saturday night would dent his pocketbook and he'd survive through to Sunday to go to church or watch football. Alcohol kept him tethered to his job; it kept him near home and suffering. Once there was the five-day workweek, the unknown man cursed Mondays and dreamt of Fridays. He often worked overtime and worked for danger pay to get gains in his paycheck. Ultimately he did these jobs for us. He risked his life to tighten bolts or paint under bridges.

If you look around at the buildings, our transportation, our processed foods, our delicacies, vices, virtues, slaughterhouses, industries, refineries, megamalls, churches, addictions, and our daily bread - you'll see the unknown man has played his vital roles in trading off his work for his paycheck. Maybe he doodled but didn't realize he created art. Maybe he took notes but he didn't write novels.

The Unknown Man built the castles and cathedrals before they became ruins. He laid railroad tracks and harvested fields, panned for gold and went to whorehouses. He worked livestock, he built the stock exchange, drilled for oil, and assembled carburetors. It was ordinary men with a lunch bucket who built St. Paul's Cathedral, the Eiffel Tower, and the Golden Gate Bridge. It was the average worker with a bag lunch who paved the roads that connected all places to all places. Then the day comes, and the unknown man is buried in the past under a cheap headstone, unremembered and unnoticed.

The unknown man dug holes, put up fences, or pounded nails. He was the pawn of the Titans of Industry. The unknown man was a number, not a name. But he was the man who kept his head down, worked through hangovers or injuries, and lived from paycheck to paycheck in order to build what society prizes – a roof over one’s head, places of entertainment, streets to stroll, and schools. The unknown man built our freedoms.

I'd tip my hat, shake his hand, pat him on the back, and buy him a beer in a momentary pause to that unspecified man we all know: the one who built this world from scratch.

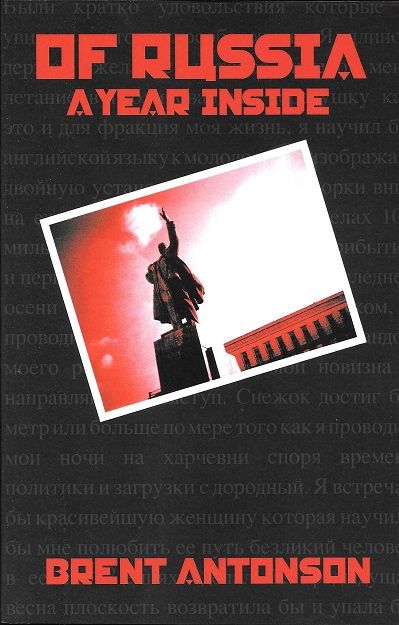

OF RUSSIA: A Year Inside

Brent (Brant is the Russian version) Antonson has seen a Russia few foreigners have. Indeed, few Russians. This young Canadian ventured to Voronezh, eleven hours south of Moscow by train, to spend a year inside a country torn by strife, fresh into a new century, and struggling with the clash between history and future. Tasked with teaching English to students at one university, and then a second, his story is riddled with romance and deception, and punctuated with near disaster and disappointment. Antonson's candor and insights set Russia on the edge of failure and achievement – much like the students he educated, filled with a dash of hope and a lump of fear. His wit did as much to get him in trouble as it did to keep him out of it.