This is a question that needs to be addressed beyond the typical mainstream academic and media views and is a complex issue that has multiple answers. At face value, it's easy to postulate that if a nation's government injects money into the economy this will dilute the money supply thus making each unit of currency less valuable.

From a mainstream perspective, it all depends on how government spending is financed. Generally, the currently accepted view is that spending is considered inflationary if it is debt-financed and that it's not so much of an issue if it's tax-financed. This view comes from the belief that the central bank buys bonds in exchange for reserves from the private banking sector in the first instance ahead of government spending. It's true, bonds are auctioned off before spending, this is to balance the Treasury General Account (TGA) at the Federal Reserve. It is noteworthy to mention that this works differently from country to country, but in aggregate can be applied to any nation to get a greater understanding of this issue. Government bonds are bought with reserves from the private banking sector. This in itself raises a question, where did the reserves that the banks have, actually come from?

The answer may be found in Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). This school of thought says, and I paraphrase, that government spending in the past created those reserves that are now used to buy bonds for current government spending. I might add that the official line of MMT is a little different and says, government spending creates reserves for the banking sector to buy government bonds. Whereas I firmly believe, it is past government spending that has created reserves in the banking sector, that is now used in the present to finance government spending.

This isn't a statement saying I disagree with MMT, in fact, I agree that the government spends reserves into existence in order for the banking sector to use those reserves to buy government bonds. In order for me to reconcile this with the reality that there are laws that prohibit the TGA from going negative, logic is needed to clarify the position, so it has become very clear to me that it's past spending that has created reserves that are used to buy bonds.

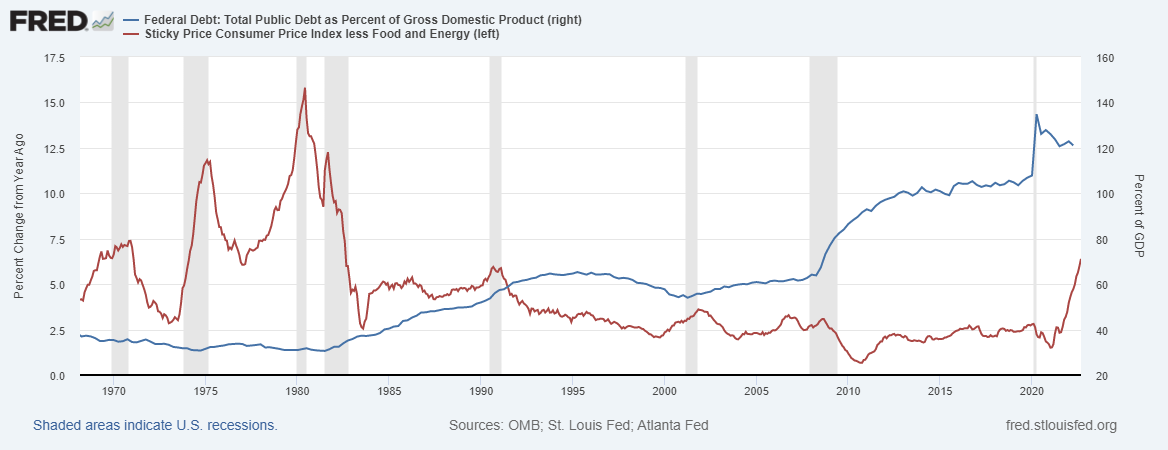

I’m not a so-called "MMT’er", but the school of thought is a great pair of glasses that one can wear to understand monetary operations from an objective standpoint. I think the first thing to address is the historical data over the past 50 years. How has government debt impacted prices, and is government spending affecting the inflation rates? You may think I said the same thing twice, but I did not. I'm describing two fundamentally different things, one being a stock and the other being a flow

It turns out that the relationship between government debt and inflation in the United States does not hold up very well as shown in the figure above. Virtually all of the spikes in inflation have been an energy constraint issue at an international level. Even though the data above excludes energy prices, those costs from energy still affect all other goods and services in the economy. Even now, the effective supply crunch we are facing globally, and the war in Ukraine are having a profound impact on prices. This has been manifested by instabilities in both food and energy costs.

The idea that spending during Covid-19 has caused the current bout of inflation is very attractive from a political standpoint in a time of so much division in our societies, but what is attractive to comfort one's mind is very rarely a reliable systematic analytical framework to proceed from. Another argument is that government spending takes resources away from the private sector thus driving up prices via competition between public and private interests.

The way I approach complex issues like this is to look at them from a systems-thinking perspective. When the federal government decides to spend, it sees an opportunity in some parts of the private sector where resources are not being employed, commonly this is called spare capacity. Obviously, if there are goods and services not being used in the private sector, there won’t be any competition for the government to use those resources, and thus there are no market pressures moving prices upwards.

In another example, let's say the resources are being used by the private sector. If the government comes in and takes over a specific sector, and in the interest of this conversation, it could be something the private sector is not efficiently participating in. Effectively by law, the government now controls this sector and sets the price. Just by a point of logic and to be politically palatable, the government will set prices in a comparable manner to the previous prices that existed when the sector was private.

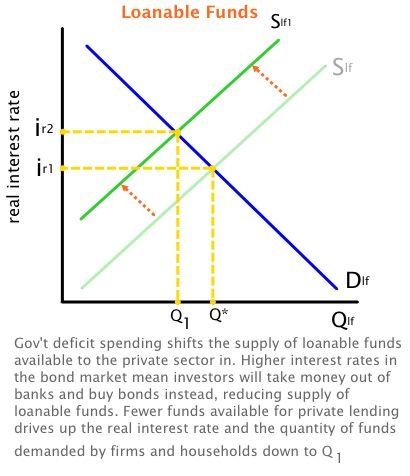

So where does the idea that government spending is inherently always inflationary? Simple... It comes from the dating ideas from long ago, in the era of the gold standard, and loanable funds model. Something that survives to this day in the academic world of economics. It’s a paradigm that refuses to die, and sadly has made economics not a science of hard or soft study in a disciplinary sense, but a cult of old ideas.

The idea of prices being in some steady state of equilibrium, however nice to think about is contrary to nature itself. In any complex system, we face everlasting oscillations. Changes in the variables of this system will no doubt change the frequency of the oscillations but will never stop the cycle itself. In fact, the day we see any system do that is the day we see that system collapsing in on itself.

When living in the moment, the allure of creating a story about the inflation cycle is so tempting it has penetrated the mainstream narrative and given us a distorted view of reality. The simple fact is that over the last 50 years, the government debt to GDP ratio has risen from 40 percent of GDP to 120 percent and has had zero effect on prices in the long term. Any correlations between government debt and price increases are purely coincidental.

Though I’m not a Milton Friedman fan, he is known for famously saying:

“Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon, in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.”

This quote has been perverted into a framework that supply is not the issue, it’s only the way you measure it that matters. The entire monetarist movement allowed the mainstream school to survive for the last 50 years, and has continued to spawn ridiculous statements like: “Government spending is really bad, so shame on you for thinking like a socialist”. Let the labels fly and divide the people with strong incendiary statements and the wheel keeps turning.

I think in closing, it is important to note that there are indeed limitations to government spending. Namely, if there are no resources available for the government to buy, this would be considered one such limitation. This is not so much inflationary, but simply a constraint. If you have money to buy apples, but there are no apples to buy, then you don't spend money on apples. Historically from my own observations, the government never attempts to buy something that's not there to buy in the first place.

The infrastructure built around economic theory has muddied the waters so much that it has created its own reality. If you want to live in that reality you can, and everything in it will appear right from your perspective. Imagine that this reality is a house, and you could live in that house. You have all the blinds closed, and don’t see the sun coming through the edges of the blinds, so you make a simplifying assumption that it must be raining. When you open the blinds you find it is not raining at all, and that it’s just night. That might be the point you decide to leave this alternative reality we are calling a house, and step outside into the real world. You start to see things more clearly and make the choices that change your life for the better and in turn, better for everyone around you. Maybe when economists fine-tune their thinking to align in this way, the world around us might be just a little bit better than it is now.