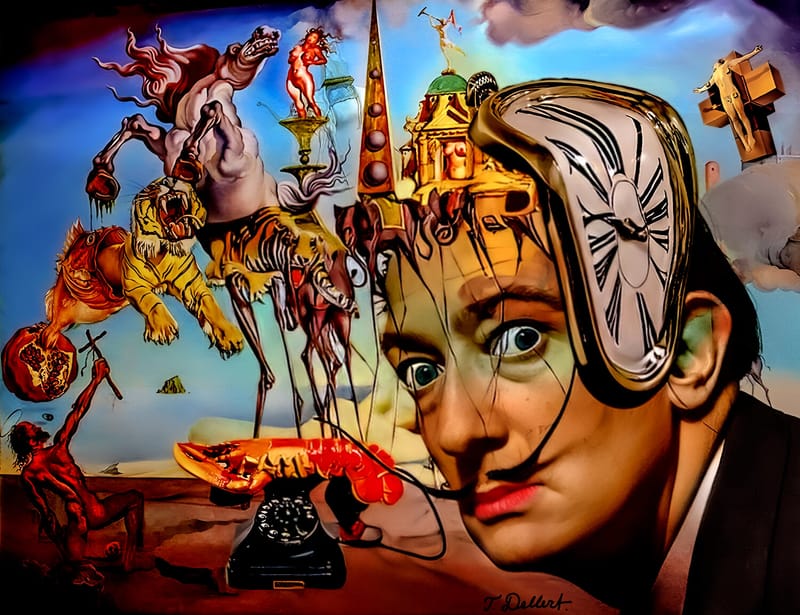

Salvador Dalí was the ultimate weirdo of the art world, a surrealist maestro who loved melting clocks, lobsters, and, believe it or not, his pet anteater. Born in 1904 in Spain, Dalí was a walking paradox, a man who thrived on being strange and provocative. He once said, "I don't do drugs. I am drugs," which pretty much sums up his eccentric persona. Imagine a guy who shows up to a fancy dinner party in a diving suit, or strolls down the street with his pet anteater, casually named "Babou." Yep, that was Dalí, always pushing boundaries and leaving people scratching their heads in bewilderment.

As an art student in Madrid, Dalí assimilated a vast number of artistic styles and displayed unusual technical facility as a painter. It was not until the late 1920s, however, that two events brought about the development of his mature artistic style: his discovery of Sigmund Freud’s writings on the erotic significance of subconscious imagery and his affiliation with the Paris Surrealists, a group of artists and writers who sought to establish the “greater reality” of the human subconscious over reason. To bring up images from his subconscious mind, Dalí began to induce hallucinatory states in himself by a process he described as “paranoiac critical.”

Despite his oddball antics, Dalí's art was incredibly well-received. His paintings, like "The Persistence of Memory" with its droopy clocks, and "Swans Reflecting Elephants," became iconic symbols of surrealism. Art critics and enthusiasts alike were drawn to his dreamlike, often bizarre, imagery. As the famous art historian Robert Hughes put it, "Dalí's art is a hallucinatory experience, a journey into the subconscious." His work was so popular that it even graced the cover of Time magazine in 1936, a rare honor for an artist at the time.

Dalí's thematic attempts in art were all about exploring the bizarre and the irrational. He was fascinated by dreams, the subconscious, and the absurdity of life. His paintings often featured distorted figures, melting objects, and strange juxtapositions, like elephants with impossibly long legs or ants crawling over a telephone. Dalí once said, "The only difference between a madman and me is that I am not mad." His art was a way to delve into the depths of the human psyche, to challenge our perceptions of reality, and to make us question what we thought we knew.

So, why did Dalí become so popular? Well, apart from his undeniable talent, it was his larger-than-life personality that captivated people. He was a master of self-promotion, a showman who knew how to grab attention. Whether it was his signature mustache, his outrageous public appearances, or his pet anteater, Dalí was a walking, talking work of art. As the writer George Orwell noted, "Dalí's paintings are not just pictures; they are events." And that's exactly what made him so beloved – he turned art into a spectacle, a performance that people couldn't help but be drawn to.

In a way, Dalí was personified by his art. His paintings were an extension of his eccentric personality, a visual representation of his wild imagination. He once said, "I am not strange. I am just not normal." And that's the beauty of Dalí – he embraced his strangeness, turning it into something extraordinary. So, the next time you see a melting clock or a lobster telephone, remember the man behind the madness, the one and only Salvador Dalí, who proved that being weird can be a work of art.

For my articles in this series, visit or bookmark the following;

Brent Antonson: Where Extraordinary Recall Sparks Insight.