The Wellspring of Well-Being

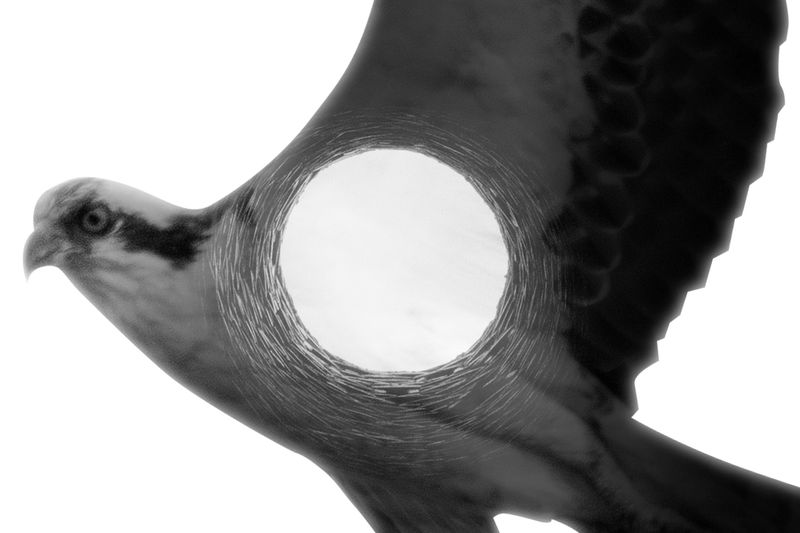

Doubtful Ascension, a Cogito, and Another planksip Möbius

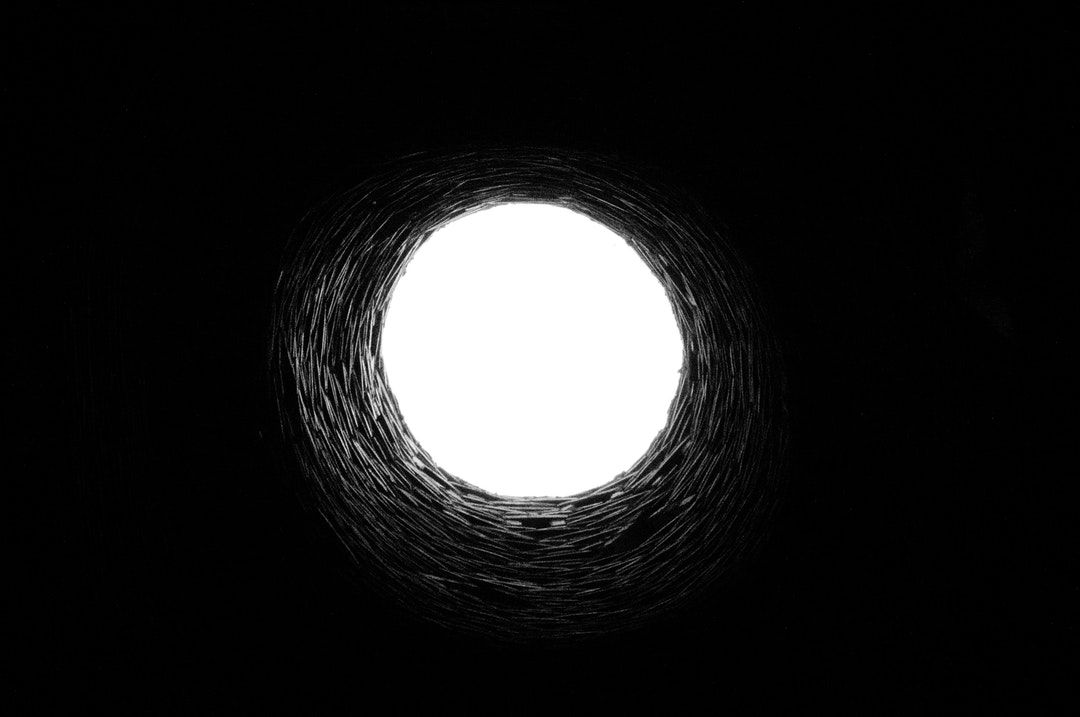

In the midst of an all-encompassing darkness, Sophia found herself gazing upward, her eyes fixating on a singular point of light. It was a stark contrast to the shadows that cloaked her. She reached up, her hand seemingly disappearing into the void as it neared the light. Sophia, ever the scholar of her own mind, chuckled softly to herself, realizing the circular shape before her was reminiscent of the mathematical curiosities she so often pondered—a möbius strip, a one-sided figure with no beginning and no end. Her life, she mused, was much like this twisted loop, where every end seemed to fold back onto itself, leading her to revisit old ideas as if they were new discoveries.

It is not enough to have a good mind; the main thing is to use it well.

— René Descartes (1596-1650)

The quote hung in the air as if spoken by the darkness itself. She had always adored Descartes for that line, a mantra she had applied throughout her years as a physicist. Today, though, it mocked her as she stood at the precipice of what could be her greatest discovery or her most profound disappointment.

How does one use a mind well? Sophia pondered this as she watched the light flicker, casting an oscillating glow on her reality. A good mind devises theories, hypotheses, laws that govern the known universe. But to use it well, she concluded, it must do more—it must enlighten, it must question, it must dare to be wrong in the most spectacular of ways.

And dare she did, as she stepped into the circle of light, her body enveloped by brilliance. The sensation was alien, a combination of falling and floating, a physical paradox that defied her extensive education. She realized that to ascend is not merely to rise, but to embrace the uncertainty of what lies beyond the next fold of space and time.

In that light, there was clarity, a humor in the cosmic joke that she, Sophia, had tried to solve the universe with equations and had instead found herself in the punchline. She laughed—a clear, bell-like sound that seemed to resonate with the light—and she ascended, though she remained firmly grounded. The möbius of her existence continued to twist.

Sophia emerged from the light, still in her darkened study, surrounded by books and papers scribbled with equations. The light, she realized, had been a figment of her imagination, a momentary lapse into a world of what-ifs. But she was smiling because the mind's journey was just as important as any physical one.

The absurdity wasn't lost on her—how a mind could travel so far while the body remained stationary. She had used her mind well, not by confirming what she knew, but by confronting the doubt of ascension. Her good mind had taken her on an odyssey, a mental spasm, if you will, that had left her feeling more alive than the countless hours she'd spent theorizing about black holes and quantum mechanics.

In the wake of her mock-ascension, Sophia found the world around her to be strangely altered, as if her brief voyage through the tunnel of light had imbued the mundane with a touch of the ethereal. Her laughter had ebbed, yet the reverberations of her solitary mirth lingered, mingling with the dusty motes that danced in the air, stirred by her passage. Her study, once a sanctuary of solemnity and science, now seemed to wear a whimsical grin on its book-laden shelves.

Alexander, her steadfast cat, leapt onto the desk with a thud that threatened to scatter her calculations to the four corners of the room. She watched him with an amused glint in her eye as he pawed at the papers, his own form of analysis. It was in these small, unexpected moments that Sophia found the levity in life, the lightness that lifted the weight of existential dread.

The immense majority of human biographies are a gray transit between domestic spasm and oblivion.

— George Steiner (1929-2020)

She spoke the words aloud, tasting the somber truth of them. Alexander paused in his paper-pawing to fix her with a gaze that seemed to penetrate the very fabric of her being. Was it possible that her feline companion understood the profundity of Steiner's observation, or was it merely the call of an empty food bowl that so captured his attention?

Sophia chuckled, scooping Alexander into her arms and depositing him gently on the floor. She decided that their biographies would not be resigned to gray transit. They would be punctuated with eruptions of joy and silliness, an affront to the oblivion that awaited all. Her research had always been driven by the search for truth, but now it was equally propelled by the pursuit of laughter.

As days turned to weeks, Sophia's study became a place of dual purpose. Equations still covered the walls, but doodles and caricatures kept them company, each a testament to an idea that had inspired joy as well as thought. Her lectures, once strict expositions of theory, now included anecdotes of Alexander's contributions to quantum mechanics—mostly theoretical, of course.

Students began to linger after class, not just to question the nature of the cosmos, but to share in the latest tale of Alexander's escapades. Sophia realized that while her mind was her greatest asset, it was the heart that gave her work meaning. Science could explain the universe, but only joy could make it bearable, only laughter could make it beautiful.

So it was that Sophia, armed with the wisdom of Descartes and the sobering reflection of Steiner, wove a tapestry of intellect and humor. She refused to let the imminent grayness of oblivion quell the vibrant spasms of life that so characterized her days. Her biography would be a riot of color against the stark backdrop of the unknown, a doubtful ascension into a realm where the cogito and the comic were one and the same.

The planksip Writers' Cooperative is proud to sponsor an exciting article rewriting competition where you can win part of over $750,000 in available prize money.

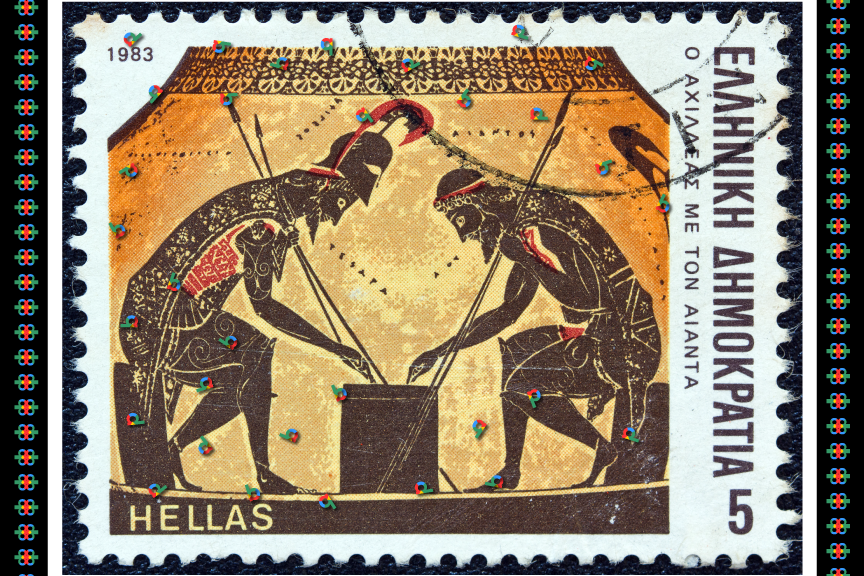

Figures of Speech Collection Personified

Our editorial instructions for your contest submission are simple: incorporate the quotes and imagery from the above article into your submission.

What emerges is entirely up to you!

Winners receive $500 per winning entry multiplied by the article's featured quotes. Our largest prize is $8,000 for rewriting the following article;

At planksip, we believe in changing the way people engage—at least, that's the Idea (ἰδέα). By becoming a member of our thought-provoking community, you'll have the chance to win incredible prizes and access our extensive network of media outlets, which will amplify your voice as a thought leader. Your membership truly matters!