Unlike the West, everything in Russia has a purpose. If it exists, there is (or was) a reason. Russians aren't known for spending extra money on things without common sense. Aside from advertising, the new agenda that took over from propaganda, very little of it gets spent to fix, build, or justify the existence of something unless that something will benefit the masses.

The suburbs of most Russian cities are usually a fortress of apartment buildings, usually five or ten stories high. The blueprints weren't very different, so the outskirts of many Russian cities looked the same.

When I look at Russia, I feel like I'm watching a movie. And I was fortunate enough to get to play a role in Russia. I got the lead part in a film I was watching.

Trains are so standard a mode of travel with such impeccable timing that you tell someone how far a city is by how long it is to get there by train. Moscow to Voronezh is eleven hours precisely.

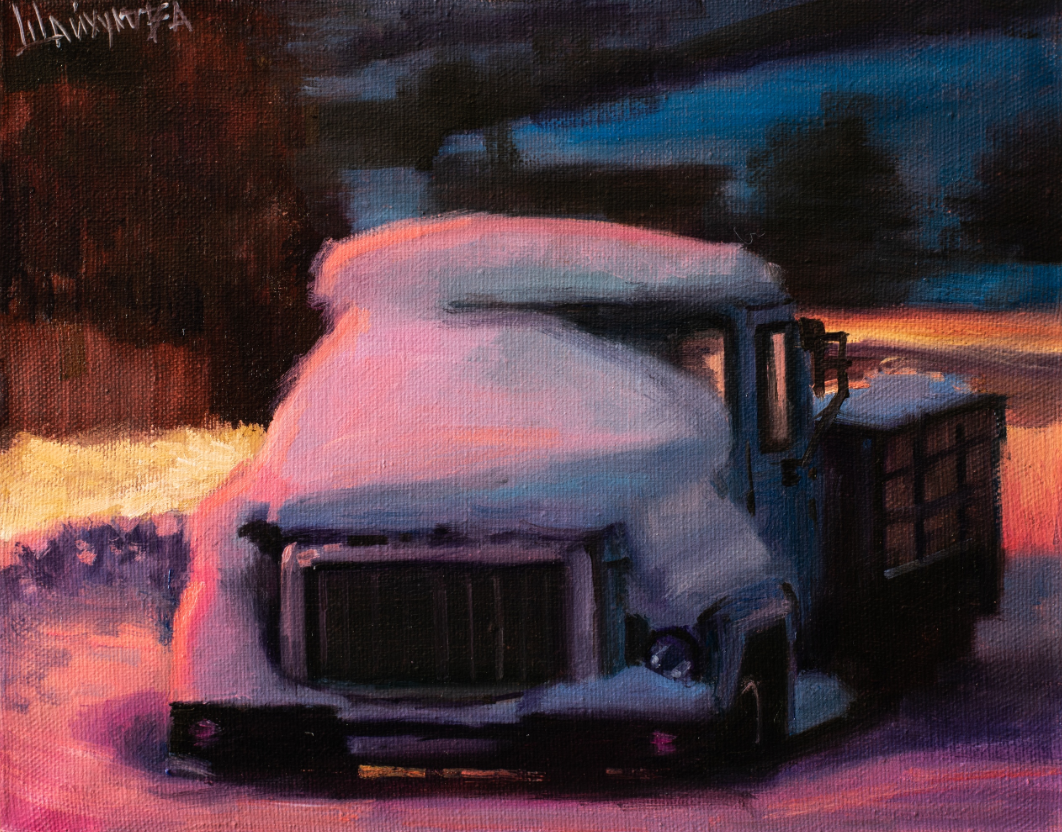

Snow seems to have its limits. It won't get higher than your knees all winter, yet it will continue to snow and not accumulate.

There is a Russian travel phenomenon called the "Taxi-bus, " a minivan driven around and around on a route with no fixed times. If it has space for you, it will stop. If not, it will just continue on its route. It's comfortable, warm, and the best way to get from one place to another using transit.

Russian traffic looks laneless and a little crazy, but the entire time I was in Russia, through the worst winter in 100 years, I saw one fender-bender, no wrecked cars or lives, just a fender-bender.

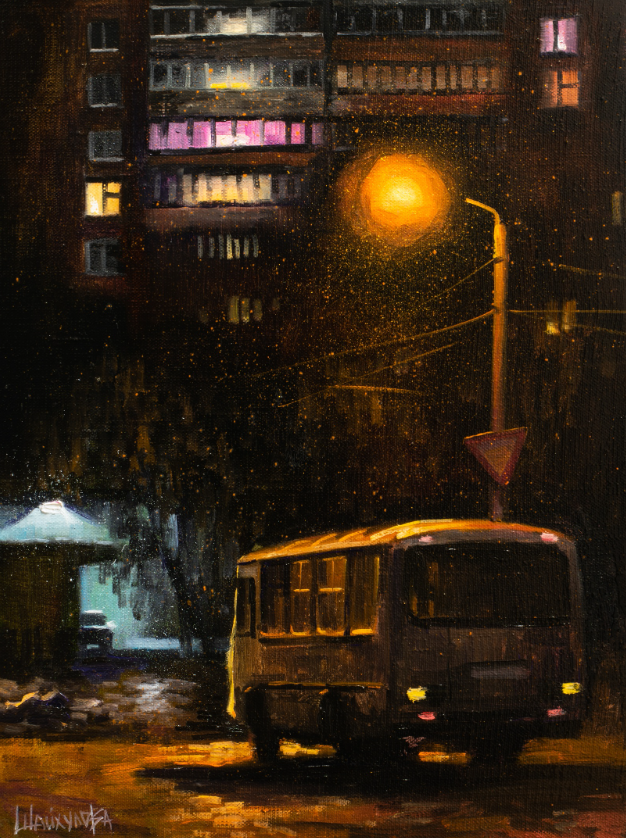

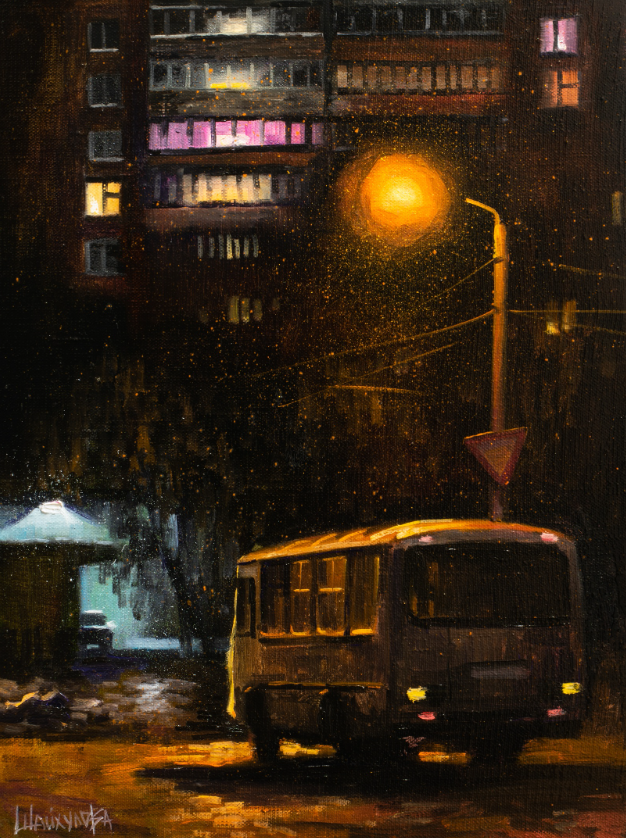

Buses and trams characterize the night. They are on the roads hogging the last of the rush hour traffic. But they can carry beyond the maximum number of people, all bent on getting home faster than awaiting another bus or tram. Somehow bending the rules works!

Russia has done with railways what America did with roads. You can get almost anywhere in Russia by train. The rail lines are akin to the American Interstates.

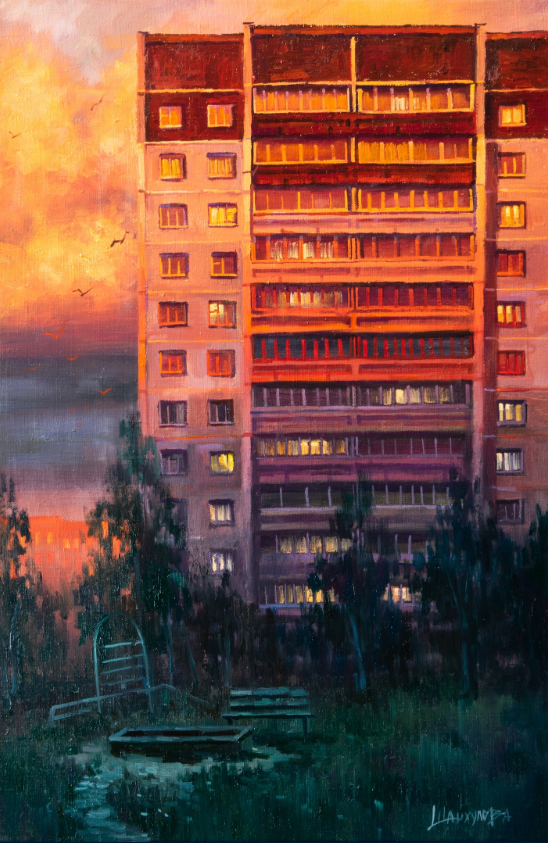

The monster apartment blocks were built under Khruschev to solve the crisis that everyone must have a home, have little style; it's all just function. They aren't beautiful or appealing, but they do, true to their word, perform the service of getting a roof over each Russian head. There are millions of stories about communal living and sharing substandard tenements, but in the dark and snowy nights, they look calm, serene, and full of social justice.

When the blowing snow piles up, some thirty feet can cover cars, so people can't even begin shovelling themselves out. This truck made it through a light snowfall.

There is a missing action scoop that Europeans frequently deal with: sharing the roads with trams. I love it. It's so authentically European. They are a part of our traffic. In America, we'd challenge the system, and there'd be too many accidents, and the trams would lose.

A friend saw this picture and confided his grandmother had lived in one identical to this for over 20 years. It's hard to appreciate having an apartment, but that the apartment is also part prison - where you keep yourself in custody. Many are drap and old-fashioned, yet many are refurbished and bright.

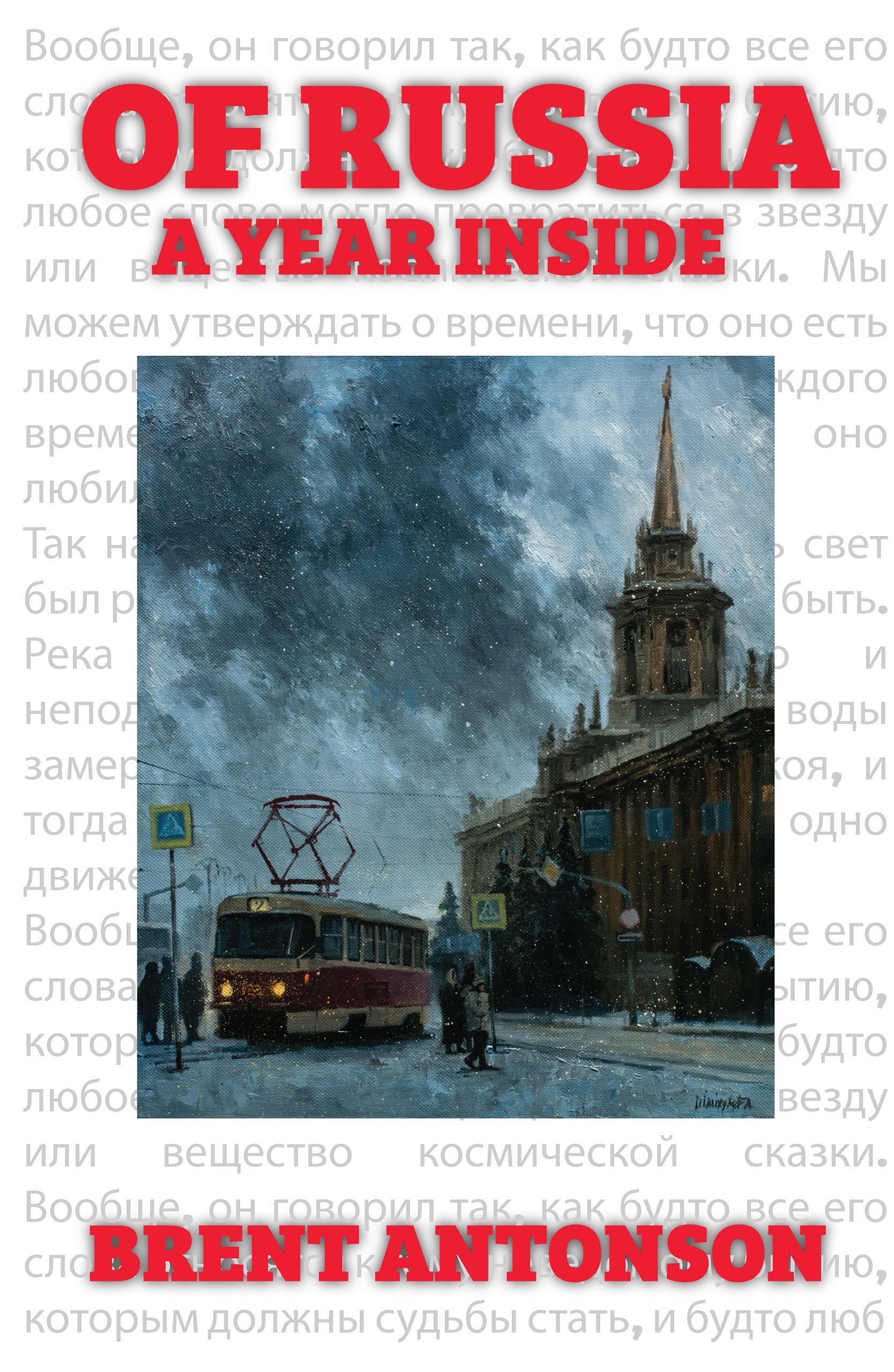

When it came to designing another cover for the second release of "Of Russia," - Альфия Шайхулова (Alfia Shaikhulova) won hands down with her portrait of the tram, the church, and the smalltown capture and exchange at a small platform. THIS IS THE RUSSIA I LOVE - IT WORKS - and I thank Alfia for using the picture to display a small Russian scene playing out in a small Russian city. Her style, talent for mixing colours, and extreme patience make for a beautiful and delicate set of "Russia: caught in the traps of an artist."

Industry pokes its head up in most Russian cities, it isn't the most beautiful of areas, but it accounts for many jobs and lives; therefore, it gets a dominant position on the skyline, often all around the city. The difference between people is some want the industrial gone from their towns, the pollution. Still, the truth is so many people can work so close to home that it makes no more sense to move it ten miles than it does to a cheaper country to manufacture all the goods, depriving the workers of their right to a job.

A solitary tram car clatters down its metallic tracks, its windows frosted in icy patterns that dance with the reflections of distant streetlamps. Within this encapsulated world, a collection of absent passengers, each a universe unto themselves—akin to figures in Dostoevsky's existential inquiries—a commune in silence.

Some scenes may look overworn, pitiful, or out of character. Many Russian cities were built up as finances became available. So children's parks or swingsets, maybe a merry-go-round, all came from different eras, so seeing a playground in Russia may make you wish for the most recent versions found in our countries. Still, there is neat archeology in how Russia transformed itself in the war years.

You are never far from a tram; they have the right of way. I find driving and sharing roads with trams one of the most European scenarios because it is a different dichotomy than the West, where accidents would abound - as we are not used to driving with these behemoths. In Europe, it's second nature.

I used to see people on busses or trams, trolleys or taxi-busses, hauling themselves from a shift at a factory or someplace where the person could barely contain themselves any longer. A long shift making widgets can scarcely be enough to cross the cities and countryside to get to work, day in, day out. I admired people who did this, but I doubt I could ever look down on a dismal day at an industrial site and know the public transit it would take to get there and back. The trams and trolleys are the quintessential workers' tools.

It's a common perception that Russia is cold and hostile to life. Russia is the largest country on earth, spanning the hottest spots in Central Asia to the north pole. That said, it does get a fantastic amount of snow, with drifts reaching 20-30 feet. People frequently lose their cars. It also has unbearably hot summers. Siberia can reach 30C.

At a high point, trams were respected and given their lead, precious real estate, platforms, signage, and place at an intersection. No one had money for cars, so they relied on transport.

Much of this has disappeared, and people are used to the times, frequencies, and bus numbers. But remember the heyday of trams when you see something like this, built for people at a time when charisma was imbued into the usefulness the travelling public needed.

This is why the artist caught my eye. Her perspectives are deadly accurate, and everything is in visual harmony. The tracks aren't distorted, and the trams don't look "off". No—this is perfection.

This feeling of perfection continues into the night with purposeful lighting and indications of living and work spaces–the space between is at the forefront of this piece.

You can structurally change the Khruschevian towers a little here and a little there, but through the decades, they all seem to resemble relatives of one another.

This picture so moved me—so made me see the artist had 'captured' a familiar scene in small-town Russia—that I made it the second edition's cover for Of Russia. The artist, a friend who connects us, and I have an exciting relationship.

Of Russia: A Year Inside

Brant Antonson has seen a Russia few foreigners have. Indeed, few Russians. This young Canadian ventured to Voronezh, eleven hours south of Moscow by train, to spend a year inside a country torn by strife, fresh into a new century, and struggling with the clash between history and future. Tasked with teaching English to students at one university, and then a second, his story is riddled with romance and deception, and punctuated with near disaster and disappointment. Antonson's candour and insights set Russia on the edge of failure and achievement – much like the students he educated, filled with a dash of hope and a lump of fear. His wit did as much to get him in trouble as it did to keep him out of it.

All artwork on this article was painted by Альфия Шайхулова (Alfia Shaikhulova)