Chornobyl – A Brief History

On April 26, 1986, reactor #4 at Chornobyl’s nuclear plant in northern Ukraine detonated. It exploded, putting 400 times more radioactive material into the Earth's atmosphere than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Nuclear weapon tests conducted in the 1950s and 1960s put some 100 to 1,000 times more radioactive material into the atmosphere.

It happened at 1:23 in the morning as a misdirected and poorly understood test was being conducted. The residents of nearby Pripyat (or the more distant city of Chornobyl) weren’t disturbed from their sleep. The local fire department responded and tried to put out the fire, but the 2,200-degree heat turned the water from their hoses into steam before hitting the actual nuclear materials on fire. All of the firefighters died quickly and horribly from exposure. For three days, the residents of Pripyat weren’t told a thing, and children played in parks, weddings were held, and people shopped and walked through the streets. When it was discovered that the accident was far greater than could have been imagined or prepared for, every resident of Pripyat was given two hours to collect some things and meet on the street. 1200 busses from Kyiv took all 55,000 residents away. They were told it would only be for three or four days.

No one has returned. Not really, a bunch of off-grid old people has reportedly moved into some cabins, but the animals, birds, and fish have returned, none of them with three eyes. But the city, Pripyat, is the world’s only Ghost-City of its kind. It is still highly radioactive (often still equal to the 30-year-old levels in places), and since it is only three kilometers from the actual reactor, Pripyat is in the nucleus of the devastation. A mere ten kilometers away, Belarus suffered most as the winds carried the furnace of radioactivity north, deep into the country. Birth defects are very common and very abnormal. Sixty percent of the fallout landed in Belarus, creating massive exclusion zones. Over 336,000 people between the two countries were evacuated and resettled. Only with the advent of the internet did groups of people, friends, and neighbors start to re-establish contact.

The discovery of the accident by Europe has quite a surprising story. The Soviets said nothing about the accident as radiation swelled in the international winds. Workers at a nuclear plant in Sweden were walking into work on a rainy day. They all failed the security/radiation test required to pass to their lockers. Someone smart deduced that the radiation was in the puddles they’d walked across the parking lots. They immediately checked the situation with every reactor in Sweden. Then they passed the query onto upwind Finland and raised their alarms. But no, Finland’s reactors were solid. It wasn’t until a US spy satellite discovered the 2200-degree smoldering core that the Soviets fessed up that there had been a small problem, and it was being dealt with.

I crossed Ukraine by rail in 2009 from Minsk, Belarus, to Kyiv. I had a ‘need’ to see Chornobyl, a personal thing few people can connect with. The world’s largest peacetime nuclear disaster site is not for everyone - and as a closet physicist, this was my Machu Picchu, my Eiffel Tower. There are two exclusion zones requiring government approval to pass. I had wanted to see Pripyat and challenge the nucleotides for a short time. Some people chase tornadoes or stand at the ocean’s edge during a hurricane. This is the same thing, except the forces are invisible. It's like a violent 30-year-old storm you can’t feel… certainly not until the first lump, or you wake up bald. An online service, passed on by our travel agent, offered a tour with lunches and stops at this place. The cost was $700 USD. With 38% of Ukraine below the poverty line, this simply seemed a ludicrous amount. But I could not find it cheaper. I didn’t want lunch and a guide to see what they wanted me to know; I wanted a few moments to stand alone on the threshold of an apocalypse. I had done tons of research and watched numerous documentaries and movies on Chornobyl, so much that it felt personal.

The disaster cost $18 billion USD (equivalent to $40 billion today) to cope with, suppress, and attempt many ways to stop, remedy, and fly in experts and workers from the country's farthest reaches. And this singular event contributed significantly to the collapse of the Soviet Union. It was the costliest disaster in modern history. Half a million soldiers, engineers, miners, and volunteers had done an astounding amount of work to shore up the broken reactor.

The core had a complete meltdown and turned 192,000 tons of uranium, plutonium, cesium-137, iodine-131, strontium-90, krypton, xenon, and much, much more into lava which burned through many feet of concrete and threatened the water table of the Dnepr River, which then would contaminate the Black Sea, then the Mediterranean. And no one wanted to think that. But their efforts successfully stopped the lava. A sarcophagus was built, an endeavor that seemed to be the only appropriate solution. There was nothing else they could do. Some of the workers in the clean-up worked 45 seconds a day; the graphite rods landed on the roof of the adjoining reactors. The radiation from the rods themselves was such that the workers could only run outside, grab a bunch, throw it off the side and then return inside until the next day. We might assume this was abused, but those are the stories... the roof was the most dangerous place for workers to be as the meltdown and radiation were all around them. Remote control tractors were brought in from West Germany, but they committed suicide by driving themselves off the roof as their wiring fried in the contamination. A shelter had to be built, one whose life expectancy was twenty years, give or take ten.

With the loss of the Soviet Union—its authority, direction, and money—Ukraine was left with a terrible secret in its north: the sarcophagus was breaking away. One hole was ‘large enough to drive a car through.’ Birds were living inside it. It looks like an old concrete building that could use some help, and even gang graffiti would have benefitted. The ugly truth is two-fold: the reactor building was structurally unsound after the explosion, yet the sarcophagus was built with the original building as support. If the roof collapses, the lava will fragment into a radioactive dust storm that will again follow the wind and likely affect all of Europe. If a collection of water on that roof collapses or enough rain penetrates to the lava, it could start a chain reaction. This could cause a nuclear explosion, rendering Europe uninhabitable for a million years. Even if neither of these possible events happens, there’s the 22,000-ton lid of the reactor problem, which was blown off in the explosion. It had flipped and landed back inside the broken core, wedged into cracking concrete. Should the reactor core split from age and drop the lid inside, the dust storm scenario again presents itself.

The enormity of the potential consequences finally got the attention it deserves. EU countries started a fund for a second sarcophagus–one of legendary engineering and labor. It promises to remove the threat by fully containing the area around reactor number four by constructing the largest movable structure ever built. The semi-circle roof was built half a kilometer from the reactor itself and the massive unit itself was built on railway tracks to slide it into position. The New Safe Confinement (NSC or New Shelter) was a structure in 2016 to confine the remains of the number 4 reactor unit, a lazy 30 years after the explosion.

The world will deal with Chornobyl again. It is currently during the Russian invasion that is governing our newsfeeds. Russian forces allegedly have the Ukrainian workers held at gunpoint. That news is a week old, and nothing currently resembling an update has emerged. So, speculation is that Chornobyl is under threat. When the tanks rolled through in late February 2022, the radioactive levels spiked 22 times their normal output.

As of March 29, 2022, as per the Jerusalem Post: Some 24,700 acres of the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone were on fire on Sunday. Commissioner for Human Rights of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine Lyudmyla Denisova said that these fires could potentially spread radionuclides to Belarus and the rest of Europe, spreading the radiation. The current situation is not in our best interest.

Did I make it to Chornobyl? I refused to pay the $700 and relied on my intuition that once in Ukraine, I could hire a taxi and head 110 kilometers north while tossing 50 dollar bills at the exclusion zone guards. But when I asked our driver, Nicolai, he said it is possible, but the paperwork takes five days at a minimum. And should it be the whim of the processing department that you take a medical examination, you must pay at your own cost, which could take days. And I had to sign a waiver saying I'd never charge the Ukrainian government lest I get cancer down the road. Chornobyl and Pripyat are back on my shelf of dreams, under C and P, respectively.

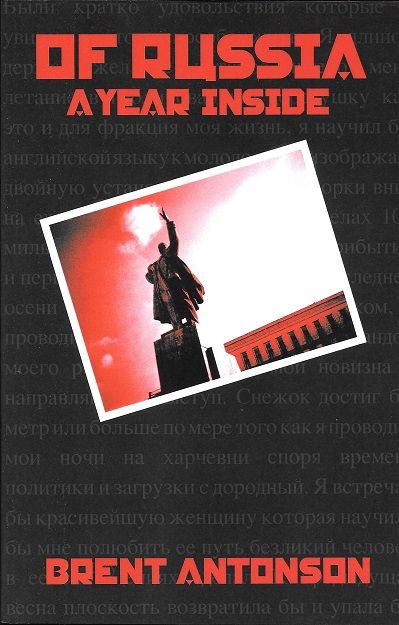

OF RUSSIA: A Year Inside

Brent (Brant is the Russian version) Antonson has seen a Russia few foreigners have. Indeed, few Russians. This young Canadian ventured to Voronezh, eleven hours south of Moscow by train, to spend a year inside a country torn by strife, fresh into a new century, and struggling with the clash between history and future. Tasked with teaching English to students at one university, and then a second, his story is riddled with romance and deception, and punctuated with near disaster and disappointment. Antonson's candour and insights set Russia on the edge of failure and achievement – much like the students he educated, filled with a dash of hope and a lump of fear. His wit did as much to get him in trouble as it did to keep him out of it.