A Critic's Meta-Review: 5/5

The Apu Trilogy (REVIEW)

Oh, boy, am I giddier than a principal at a pep rally right now. It feels as if I’ve just been presented with a piping hot plate of pecan pie, topped with an Arctic Sea-sized serving of hand-churned homemade ice cream (of the butterscotch variety, with a few spoonfuls of peanut butter to keep it all glued together) and doused in the most decadent of caramel sauces.

None of that sugar-free nonsense (sorry, doc, but daddy’s eating good tonight).

“What gives?”

Perhaps you may find yourself asking this question. In fact, it is quite likely that you have already asked it and have now moved on to a number of follow-up questions pertaining to my physical health. Well, I can assure you that I am in perfectly fine shape. Don’t believe me? Here, I’ll run a mile right now to prove it.

…

…

…

Alright.

I’m back. Just ran that mile. Nice day out. Anyways, that should take care of the latter set of queries. As to the initial inquisition into the reason for my high spirits - allow me to explain.

I have just fallen in love with who I am.

A mediocre writer/amateur blues guitarist/dilettante chef from the suburbs of Chicago?

Nope.

An Indian (as in “from India” - a distinction that, unfortunately, must still be made regularly in order to avoid being met with the follow-up question: “Oh really? What tribe?”)

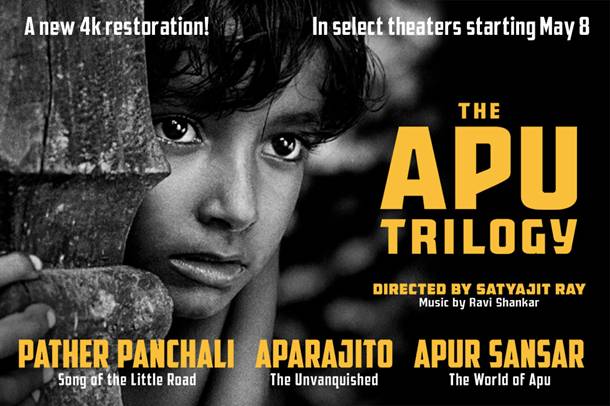

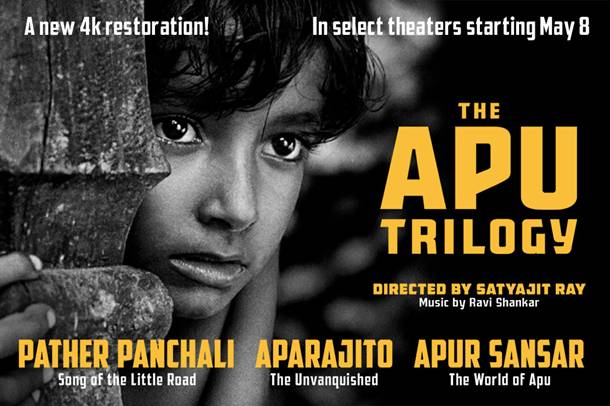

This newfound infatuation with my roots has come about as a result of watching Satyajit Ray’s iconic “Apu Trilogy” - which, contrary to what you might be thinking if you are not familiar with the history of Indian cinema, is not about the guy who runs the Kwik-E-Mart on The Simpsons.

Nay, this trilogy is based on two novels by a Bengali author by the name of (get ready for this one) Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay (I would call him B.B. for short but that name has already been taken to the next level by a trailblazer in another field). The two novels are Pather Panchali (“The Song Of The Road”) and Aparajito (“The Unvanquished”), which also happen to be the titles of the first two films in this trilogy. The final installment, however - Apur Sansar (“The World Of Apu”) - is the one that really ties it all together.

Despite the slight differences between Bangla (the language in which these movies are in) and Hindi (the language I have been brought up to speak by my mother - one that I wish I understood more of), these are films that cut across all cultural bounds in terms of how they will touch the heart of any desi (a term used to refer to anyone from the Indian subcontinent, whether that be Pakistan, Bangladesh, or India itself) who happens to view them. In fact, I would even wager to say that anyone of any ethnic background will be able to relate in some way to these films, as the story of Apu and his family is more of a story about socioeconomics than it is about any one culture in particular.

If your family ever struggled to put food on the table, if your father has ever been stuck in a dead-end job that didn’t satisfy him and wanted more out of life, if your mother has ever been pushed to her breaking point by all of the pressure surrounding her, if you ever experienced the loss of a loved one at an early age, or even if you just had a childhood in which you found solace in the little things - like splitting a guava with a crazy old lady or dancing in the rain - then you will find yourself nodding along to the plot of Pather Panchali.

If you have ever felt the urge to break out of the life that those around you, attached to tradition, have planned for you, if you ever had to work long and work hard into the wee hours of the night just to be able to finance your dreams, if you’ve ever had to face the conundrum of not wanting to abandon your lonely, loving mother while also exploring the vast world that awaits you, or - on the flip side - if you have ever had a child that you cherish so dearly and would do anything to protect, but also one that you know deep down you must eventually let go of in order to allow the blossoming to take place, well, then you’ll get goosebumps watching Aparajito.

And if you’ve ever been forced to reckon with the fact that perhaps the dream you’ve been chasing wasn’t the role you have been destined to perform - but, nonetheless, was a worthy endeavor to have pursued in that it prepared you for what you ultimately must do with your life, then you will be swimming in tears by the time that beautiful Bangla inscription that translates to “The End” appears following The World Of Apu’s final scene.

Now, if you for some reason cannot relate to any of those things (which is entirely possible since, upon rereading them, they seem quite directly drawn from my own life), surely you will at least be able to savor the gorgeous score - which was composed by Ravi Shankar after only being presented with a few scenes from the films and being told to just play whatever came to him upon viewing them. And even if you’re not so hot on the sitar or the flute (which is a rather unfortunate predicament to be in), you can undoubtedly appreciate the fact that these films were made on a shoestring budget - Pather Panchali was supposedly made on a budget of one hundred and fifty thousand rupees, which is less than five hundred thousand U.S. dollars in today’s money.

Low budget, and yet the furthest thing from low quality. As a matter of fact, I have just sifted through a list of the most expensive films ever made, and not a single one of these even comes close to the level of sheer excellence achieved by Satyajit in this trilogy. A lot of them seem to be superheroes, which is all well and good of course. That being said, I can’t think of a single superhero that comes close to the level of honor, selflessness, and general badassery displayed by little Apu’s older sister - his didi - Durga in the first film.

This is not to scrub dirt all over Hollywood’s big budget bonanzas, either, as I have yet to see a Bollywood film that is capable of inducing the emotions I experienced while watching these films. With their hokey song-and-dance routines, silly plots, cheesy dialogue, and gratuitous overacting, Mumbai sure ain’t putting out nothing like this these days (save for the rare gem, but those are few and far between).

And speaking of acting, I would be remiss if I did not take a moment to highlight how brilliant all of the performances are throughout these films. To think that these were all amateurs - Lord, it truly blows my mind. Each and every one of them, from the young baachen (perhaps the best actors of the bunch - certainly the most expressive and the most relatable, in my estimation) to the old buddhis (particularly Apu’s great aunt, prominently featured in the first of the flicks, who gave a performance more genuine than anything you are likely to see on a screen this side of a literal documentary). How Satyajit Ray was able to get so much out of these folks despite their relative inexperience in the realm of cinema is beyond me.

But it shouldn’t be. The man is a genius. This fact becomes quite evident upon an even casual observation of how this film is shot - the way he is able to capture the simple things that we all notice and take to be beautiful but would never think to capture on film. Things like rain falling on a river, or dough for roti being slowly rolled with the grace of a potter preparing clay - these fragments of a life well noticed are all present throughout this trilogy.

This is why I believe this is the best trilogy ever made. Forget Star Wars, forget Lord Of The Rings - as great as they are, and they are all certainly great films (well...for the most part, regarding Star Wars), they do not even come close to the level of mastery contained in this trilogy. That is because, ultimately, they offer us an escape from the real world. Don’t get me wrong - escapism is cool and all, as it allows us to return to reality with a newfound perspective on how things could be and, many times, how they are at a deeper level than we are capable of comprehending by simply observing the way things seem to be in our daily lives.

The Apu Trilogy defies the odds. It is as real as it gets. Never have I seen something so authentic - even most documentaries don’t come close. Satyajit Ray was apparently inspired by a lot of the output from the Italian neorealist era - movies like Vittorio De Sica’s Ladri di biciclette (“The Bicycle Thief”) and Giuseppe De Santis’s Riso Amaro (“Bitter Rice”) that came out in the period following World War II, depicting the life of average, everyday Italians and the struggles they and their families experienced as a result of the fallout from the fascist age.

And yet, despite its commitment to verisimilitude of the utmost degree, it has a lot to say about the world that it depicts - and this can be seen by just about anyone who watches it. You see, it has been said about poor folks in the United States that they largely view themselves as “temporarily embarrassed millionaires” - likely the reason why socialism never really caught on around here (this is not to say us pinkos should give up hope, though).

With this trilogy, Ray makes it clear that poverty is far from a transient condition - far from it, in fact. It is a lifestyle, and one that is virtually impossible to escape once one is born into it. For every Horatio Alger, there are a million Apus, dreaming of a world that the conditions they are bound by will never allow them to live in. They are trapped in a cycle that may improve incrementally with each passing generation, but will never fully cease. At least, this is how it is for most of the world’s poor - who, contrary to popular belief, are not all huddled up in a hut somewhere in Burundi.

They are right here in our backyard, too. Just take a trip down to rural Appalachia if you don’t believe me.

But I digress.

I guess, more than anything, films like these remind me why I no longer am embarrassed of my heritage. You see, back in the day - I am talking pre-Corona times here, which I know can be a little hard for us to imagine in these crazy, crazy times - I was deeply ashamed to tell people that I was Indian. Growing up in the Midwestern United States during the Bush era, in the wake of 9/11, was not easy for the brown among us. The amount of times I was called a “terrorist” by my peers (and even some of their parents, when I would play against their kid’s team in basketball or something) is innumerable. I can still remember a girl in one of my grade school classes asking me if my family was related to Osama bin Laden. Despite the geographical inaccuracy behind statements like these, they kept coming well into my adolescence - to the point where, upon returning from a trip to India with my family back when I was a freshman in high school, I lied and told everyone I had been in London instead. Being told that I couldn’t come over and hang out because I probably still “reeked of curry” was not really high on my list of wants.

But now it is. Shoot, I hope I reek of curry - means I’m eating good!