Summary

- Life on earth is dominated by plants – they make up 82% of global biomass.

- The animal kingdom makes up just 0.4% of global biomass.

- Humans account for just 0.01% of biomass. However, our livestock outweighs wild mammals and birds ten-fold.

- 86% of life is in terrestrial environments; 13% in the deep subsurface; and just 1% in marine environments.

- We have identified and described over two million species on Earth.

- Estimates on the true number of species varies. The most widely-cited estimate is 8.7 million species (but this ranges from around 5 to 10 million).

- The tropics are home to the most diverse and unique ecosystems. They tend to have the most endemic species.

Biodiversity on Earth today

- Humans make up just 0.01% of Earth’s life – what’s the rest?

- Oceans, land and deep subsurface: how is life distributed across environments?

- How many species are there?

Humans make up just 0.01% of Earth’s life – what’s the rest?

Our planet is home to an incredible diversity of organisms. What does the earth’s biodiversity look like in the big picture?

In this post, I provide an overview – with a summary graphic – of Earth’s biomass, how it is distributed between taxa (the taxonomic group of organisms), and the environments within which they live. This summary is based on the findings of research by Bar-On, Phillips & Milo published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).1

Humans account for just 0.01% of biomass

There are several ways we can answer the question of how much life is on Earth. We could, for example, count the number of species, population sizes or the number of individual organisms. But these metrics can make it difficult to compare taxa: small organisms may have a large population but still account for a very small percentage of Earth’s organic matter.

For a meaningful comparison, Bar-On et al. (2018) quantified life using the metric of biomass. Biomass is measured here in tonnes of carbon as it is a key building block of life.2

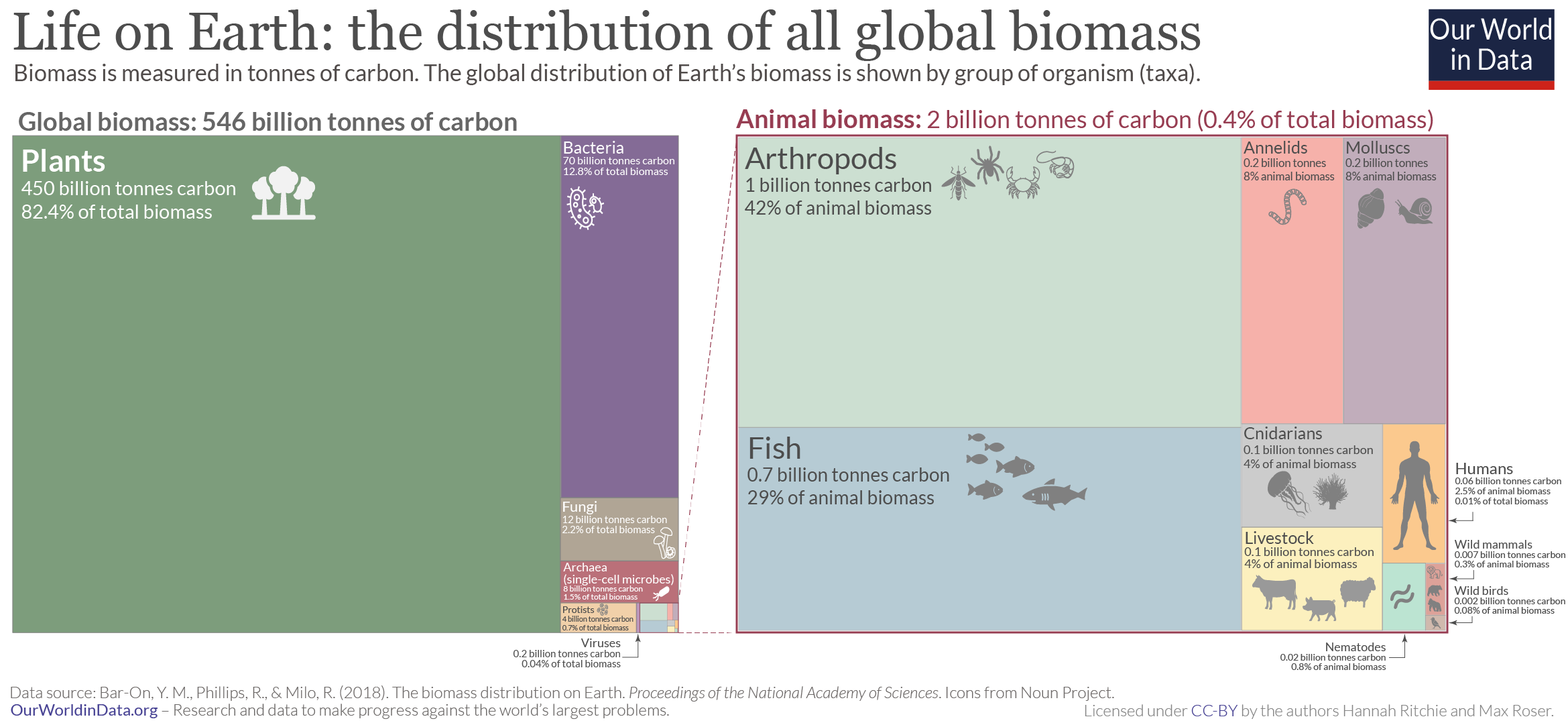

In the graphic below I summarize the distribution of global biomass by taxonomic kingdom (on the left), with a magnified snapshot of the animal kingdom (on the right).

What are the stand-out points?

- plants – mainly trees – dominate life on Earth: they account for more than 82% of biomass;

- surprisingly in second place is the life we cannot see: tiny bacteria sum up to 13%;

- whilst our perceptions are often focused on the animal kingdom, it accounts for only 0.4%;

- humans account for just 0.01% of the biomass, so we’d need about 70 trillion of us to match Earth’s collective biomass.3

Livestock outweighs wild mammals and birds ten-fold

Humans comprise a very small share of life on Earth — 0.01% of the total, and 2.5% of animal biomass [animal biomass is shown in the right-hand box on the visualization above].

But we are also responsible for the animals we raise. Humans alone may seem insignificant, but our hunger for raising livestock means we have played a major role in shifting the balance of animal life: livestock account for 4% of animal biomass.4

Livestock accounts for more biomass than all humans on earth; more than 50% greater than humans.

And livestock accounts for much more than all wildlife: Wild mammals and birds collectively account for only 0.38% — livestock, therefore, outweighs wild mammals and birds by a factor of ten.5

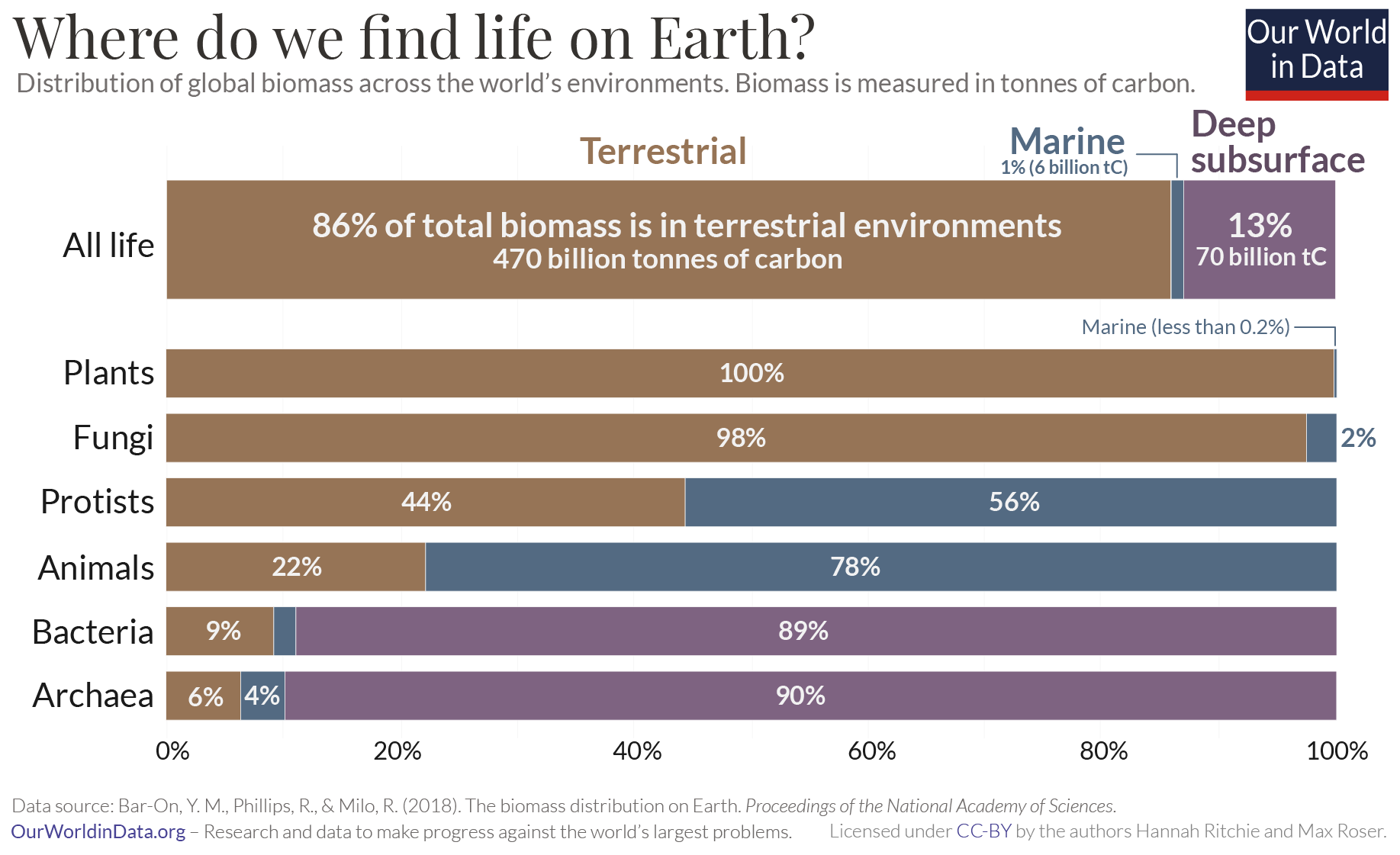

Oceans, land and deep subsurface: how is life distributed across environments?

The visualization here provides a snapshot of how life spans the planet’s environments. This summary is based on the findings of research by Bar-On, Phillips & Milo published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).6

There are three high-level habitat environments: land, marine, and deep subsurface environments. Deep subsurface environments can be terrestrial or below the ocean floor, but represent habitats deep below the surface – extending from around 50 metres to thousands of metres below the surface.7

Most of life exists on land — 86% of biomass. This is because almost all plant life – mostly trees – is terrestrial. The authors estimate that marine plants, for example, seaweed, make up less than 1 billion tonnes of carbon. This is less than 0.2% of total plant biomass.8 Most bacteria and archaea exists in the deep subsurface, meaning 13 percent of global biomass thrives in this environment.

Despite dominating our planet in terms of area and volume – taking up more than 70% of global surface area – the oceans are home to just 1% of biomass. But they do dominate the animal kingdom: 78% of animal biomass lives in the marine environment.

With lifeforms ranging in size from the microscopic cellular level to large lifeforms that span tens of hectares,9 it is impossible to contextualize life on Earth through experience or intuition alone.

Just look at the viruses that live in the sea: while each one of them is tiny, if we placed all the viruses end-to-end they would stretch for 10 million light years. That is around 100 times the distance across our own galaxy.10 On land the scale is just as mind-blowing: there are more than 1016 prokaryotes in a ton of Earth’s soil – orders of magnitude more than the ‘mere’ 1011 stars in our galaxy.11

Looking at the big numbers allows us to understand our planet and our place in it.

How many species are there?

How many species have we described?

Before we look at estimates of how many species there are in total, we should also ask the question of how many species we know that we know. Species that we have identified and named. This is only a fraction of the actual number of species on Earth because there are so many that we haven’t yet found or studied.

The IUCN Red List tracks the number of described species and updates this figure annually based on the latest work of taxonomists. In 2020 it listed 2.12 million species on the planet. the chart we see the breakdown across a range of taxonomic groups – 1.05 million insects; over 11,000 birds; over 11,000 reptiles; and over 6,000 mammals.

These figures – particularly for lesser-known groups such as plants or fungi – might be a bit too high. This is because some described species end up being synonyms – the description of already-known species, simply given a separate name.12 There is a continual evaluation process to remove synonyms (and most are removed eventually), but often species are added at a faster rate than synonyms can be found and removed.13 To give a sense of how large this effect might be, in a study published in Science, Costello et al. (2013) estimated that around 20% of the described species were undiscovered synonyms (in other words, duplicates).14 They estimated that the 1.9 million described species at the time was actually closer to 1.5 million unique species.

If we were to assume this “20% synonym” figure held true, our 2.12 million described species might actually be closer to 1.7 million.

Regardless, we know that any of these figures are an underestimate of the actual number of species. The fact that there are so many species that we’ve yet to discover has real consequences for our ability to understand changes in global biodiversity and the rate of species extinctions. If we don’t know that certain species exist, we also don’t know that they might have, or will soon, go extinct. Some species will inevitably go extinct before we realize that they existed.

How many species are there really?

| Kingdom | Number of species (Total) | Number of species (Ocean) | Number of species (Terrestrial) |

| Animals | 7,770,000 | 2,150,000 | 5,620,000 |

| Chromists | 27,500 | 7400 | 20,100 |

| Fungi | 611,000 | 5320 | 605,680 |

| Plants | 298,000 | 16,600 | 281,400 |

| Protozoa | 36,400 | 36,400 | 0 |

| Archaea | 455 | 1 | 454 |

| Bacteria | 9680 | 1320 | 8360 |

| Total species | 8,750,000 | 2,210,000 | 6,540,000 |

How many species do we share our planet with? It’s such a basic and fundamental question to understanding the world around us. It’s almost unthinkable that we would not know, or at least have a good estimate, what this number is. But the truth is that it’s a question that continues to escape the world’s taxonomists.

As Robert May summarised in a paper published in Science15:

If some alien version of the Starship Enterprise visited Earth, what might be the visitors’ first question? I think it would be: “How many distinct life forms—species—does your planet have?” Embarrassingly, our best-guess answer would be in the range of 5 to 10 million eukaryotes (never mind the viruses and bacteria), but we could defend numbers exceeding 100 million, or as low as 3 million.

Over decades, researchers have made a number of wide-ranging estimates. As May points out, this ranges anywhere from 3 to 100 million – two orders of magnitude of difference. Most modern estimates fall within a tighter range.

One of the most widely-cited figures comes from Camila Mora and colleagues; they estimated that there were around 8.7 million species on Earth today.16 Mora et al. put an uncertainty of 1.3 million species around this figure. The breakdown of how many of these species are animals; fungi; plants; and other groups is shown in the table. This also shows the split between marine and terrestrial environments. It’s estimated that 2.2 million of these species lived in the ocean.

There are also a range of other estimates: Costello et al. (2013) estimate 5 ± 3 million species; Chapman (2009) estimates 11 million; and after reviewing the range in the literature, Scheffers et al. (2012) choose not to give a concrete figure at all.17 There is typically strong agreement on the most well-studied taxonomic groups such as mammals, birds, and reptiles. Where most of the disagreement lies is in insects, fungi, and other smaller microbial species. Reaching consensus on such small and inaccessible lifeforms is undoubtedly hard.

How can we even begin to make these estimates? There are several approaches that researchers take.

Mora et al. (2011) – whose estimates are shown in the table – used the fact that there are predictable relationships in higher taxonomic classifications of life, that could be extrapolated to the species level. Life can be classified at multiple levels: each belongs to a kingdom (e.g. the “Animalia” kingdom – this sorts life into animals, plants, fungi etc.); then a phyla (e.g. “Mollusca” or “Arthropoda” in the animal kingdom); then class; order; family; genus; and finally the species level. We know much more about the higher taxonomic classifications (kingdoms, phylum; classes) than we do about the specific species-level breakdowns. But, we find that for groups of species that have been well-studied, we find predictable patterns between the higher taxonomic classifications and estimates at the species level. Researchers can use these predictable patterns for well-known species and apply them to lesser-known groups.

The honest answer to the question, “how many species are there?” is that we don’t really know. Some estimates span several orders of magnitude, from a few to 100 million. But most recent estimates lie somewhere in the range of around 5 to 10 million.

Biodiversity across the world

The world is home to millions of species, each adapted to different environments: tropical, temperate, polar; terrestrial; freshwater or marine; high or low altitude; dry; wet or a mixture of both. Most places on Earth are home to at least some unique species, but the density of biodiversity varies a lot across the world’s continents.

The following maps show the density of endemic species by country across a range of taxonomic groups. Endemic species are those that naturally occur in only one geographical locations. In other words, they are unique to that place.

What we see is that the tropics is incredibly dense in unique wildlife. In almost every map we see a bright belt along the equator – this is true of mammals, birds, coral reefs, amphibians and a range of fish species. It’s estimated that tropical forests alone are home to more than half of the planet’s species.19 This is important because, unfortunately, this also where the greatest threats to wildlife exist today. It’s where 95% of deforestation occurs, and where most mammals, birds, amphibians and reptiles are hunted and poached. If we want to protect these species we need to first understand where they live; what the pressures are; and what we can do about it.